SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – In a crowded gymnasium in General Santos City, Richard Tang Jr of South Cotabato donned his tribalwear to accept a long-awaited land ownership certificate from President Rodrigo Duterte himself.

He listened to Agriculture Secretary Manny Piñol say that it took Duterte’s “political will” to get various agencies to work together and issue the awards.

And so during a television interview, Tang was overjoyed. “Marami pong salamat kay Presidente Digong, Rodrigo Duterte. ‘Tay, maraming salamat kasi nabigay mo na sa amin ‘yung titulo ng lupa namin at pasalamat din kami sa pagmamahal mo sa aming mga Lumad.”

(Thank you very much to President Digong, Rodrigo Duterte. Father, many thanks to you because you gave us our land titles. We also thank you for your love for us, Lumad.)

On the other side of the world, physical therapist Kelly Dayag, from his apartment in California, said Duterte may have a foul mouth, but at least he helps poor Filipinos.

“We cannot focus on political correctness, ‘disente-disente (decency)’ which cannot put food on the table of ordinary Filipinos,” he told Rappler.

“I’d rather have a President like that, rather than ‘holier than thou’ who has stolen lots of money or is abusive and corrupt,” he continued.

This is the Philippine President, a man who has forced Filipinos to make a choice. Either you tolerate his faults and benefit from his virtues, or you coast along with the usual boring politician who’s never gotten the country anywhere.

You get rape jokes, but he’ll clean up Boracay. Your God gets called stupid, but you’ve got free college education for your kids.

It’s a choice some Filipinos have had no problem making. Others have had to make difficult compromises, necessitating an internal shift in values and then an external commitment that has led to unfriended friends and heated family arguments. (LISTEN: PODCASTS: Duterte, ruler of a divided nation)

Voting Duterte, for many, was a gamble and in the midway point of his presidency, June 30, 2019, Filipinos are now assessing if they made the right bet.

Popularity despite odds

The “iron-fisted” Davao City mayor of 2016 won on the strength of 16.6 million votes – 39% of all votes cast in a 5-way race.

Nearly halfway into his presidency, 79% of Filipinos, never mind just the voting population, declared satisfaction with his leadership, according to a Social Weather Stations (SWS) survey in March.

Duterte has kept his honeymoon period going for two years and 3 quarters of a year. SWS defines a president’s honeymoon period as a time when he or she is able to maintain a net satisfaction rating of at least +30, the minimum rating for a grade of “good.”

His March net satisfaction rating was +66, which, along with his June 2017 rating of the same number, is his highest so far.

Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea, explaining Duterte’s high ratings to Rappler, said, “It’s simply because of his performance and the trust they (Filipinos) have placed on him.”

As far as popular presidents and survey ratings go, it remains to be seen if Duterte would beat the record of his predecessor Benigno Aquino III, who enjoyed a honeymoon period that lasted 3 years and 3 quarters.

But the best seal of approval from Filipinos was the electoral victory of 9 pro-Duterte candidates in the 2019 senatorial elections. Filipinos were completely fine with no opposition candidate making it to the Senate, a chamber often seen as Philippine democracy’s last stand.

With his allies dominating the chamber, Duterte’s agenda of reviving the mandatory reserve officers’ training course, death penalty, possibly extending martial law, and lowering the age of criminal responsibility seems all but unstoppable.

This midterm victory at the polls means that, entering the last half of his presidency, Duterte is no lame-duck Chief Executive.

That Duterte has managed to keep these high numbers and his political clout going is curious, even tear-out-your-hair frustrating for some, given controversies he’s faced that would have toppled other presidencies.

Would Filipinos be as readily forgiving if Cory Aquino or Joseph Estrada called God “stupid” and said women are raped because they are beautiful?

The Duterte presidency is an extraordinary time.

In the first half of his presidency, Duterte’s governance style has become clearer. He governs largely through instinctive messaging unfiltered and unburdened by the usual vetting and consulting processes.

The emphasis is getting his message across and getting things done. In this vein, he has clamped down on critics and bureaucracy that get in his way – making him appear heavyhanded and dictator-like. It’s also for the sake of getting things done that he lavishly rewards allies and puts them in high places.

But it’s this same “do at all cost” attitude that has endeared Duterte to the masses, and even impressed some critics. His push for free public college education, increase in senior citizen’s pension despite the protestations of his economic team, amped up land reform, and support for universal health care has affirmed Duterte, in the eyes of supporters, as a man for the people.

“I’d rather be criticized on the side of being brutal than allow my country to just disintegrate,” he said on January 28.

What else did we see during the first 3 years of Duterte’s leadership?

Presidential podium as pulpit and command center

Duterte’s most used presidential tool is his podium. It is behind the rostrum that he truly governs. Duterte uses his hours-long speeches to set the tone of his administration either in general or when it comes to a specific new issue.

It’s from where he deflects or responds to criticism, from where he attacks critics, from where he projects strength, and even from where he barks orders.

There have been many instances when Cabinet members only hear of a new policy during a Duterte speech as when he announced his “separation” from the United States, his closure of Boracay, and his plan to send back Canada’s illegal garbage.

It’s a strategy he perfected as mayor when he would use his Sunday show to declare city-wide policies, that, until the show, city staff (who make sure to tune in) had never heard of.

Duterte makes these surprise announcements because these new policies are part of the message, maybe even primarily for messaging purposes. Why else allow Cabinet members to make adjustments in implementation down the road? For Duterte, his mere utterance that he will do this, the shock and awe of it, accomplishes his goal of making a point.

His speeches are also his way of commanding loyalty. Talk to any supporter and they will say he is loved because his words resonate with ordinary folks.

“Duterte speaks the language of the common Filipino people. The message of the President resonates at the heart of the common Filipino people,” said Dayag when asked why Duterte remains so popular.

Whether it’s giving instructions on how to use Viagra or joking that he’ll kick St Peter’s rooster at heaven’s gate, Duterte never runs out of amusement for his supporters.

Those who might have misgivings about such inappropriate remarks are appeased when they hear Duterte rail against “elitists” and unfeeling “Dilawans,” grievances they too carry in their hearts.

Duterte’s messaging kicks into high gear when deflecting controversies. He made sure to respond to the stickiest news items or commentaries.

To allegations of abuses in the drug war, Duterte said the vigilante killings are not state-sponsored. To then-preidential aide Bong Go’s alleged intervention in a billions-worth military project, Duterte said no government contracts land on his desk. To concerns over his graying pallor and health, he said he got a sunburn or suffered from a skin treatment mishap.

His responses may not satisfy the more critical citizens, but they’re enough for the faithful flock and his allies.

Twisting the law, facts

“I will not order anything that is not legal. I cannot do that because I am the President. What comes out from my mouth is already a well-thought of way of doing it,” Duterte said in an interview with his good friend Pastor Apollo Quiboloy on June 8.

Ideal-sounding it may be yet Duterte has publicly ordered massacres of drug addicts (with promises of promotion to cops) and “joked” he would take the blame for rapes by his soldiers during martial law in Mindanao.

Duterte has led or backed some legal maneuvers that have been widely questioned. These have led to 3 cases of first impression during Duterte’s presidency so far.

First, the quo warranto ouster of Supreme Court Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno in Duterte’s 2nd year as president was criticized as being in violation of the Constitution which states that a chief justice can only be removed through impeachment

The ouster via quo warranto petition was initiated by Solicitor General Jose Calida, with Duterte publicly backing it later on.

Second, Duterte “invalidating” the amnesty granted to Senator Antonio Trillanes IV, one of his most vocal critics. The President was accused of “reinventing the law” and citing spurious arguments about his power to revoke amnesty. In the end, a judge ruled against Duterte’s theory that Trillanes never properly filed his amnesty proclamation and thus should not be allowed to enjoy amnesty.

Third, Duterte’s unilateral withdrawal of the Philippines from the International Criminal Court (ICC). As with the Trillanes amnesty issue, Duterte again made use of the “void ab initio (void from the start)” principle to claim the ICC has no right to try him for drug war abuses because the Philippines was never an ICC member in the first place.

Some lawyers snickered at his 16-page argument, seeing it as just another way out of a tight spot. At the time, the ICC had announced it was beginning a preliminary examination of alleged human rights violations in Duterte’s illegal drugs crackdown.

Then there’s Duterte’s lack of rigor, and sometimes outright disdain for truth-telling. He has admitted to “making up” a bank account number to ruin Trillanes’ reputation, falsely claimed his hometown of Davao City does not get government projects, and baselessly accused ICC judges of being pedophiles.

Use of ‘intelligence,’ diagrams vs critics

From the start, Duterte had been criticized for the 400% increase in intelligence and confidential funds allocated to his office. Fast-forward 3 years later, Duterte has used so-called “intelligence services” as basis for serious accusations against critics.

These intelligence reports are publicized in the form of diagrams, often by Duterte himself in specially-called press conferences.

There was the diagram alleging Senator Leila de Lima’s involvement in prison drug trade. De Lima was eventually jailed on drug charges and has remained in prison for over two years.

There was the diagram supposedly showing corruption by former cop Eduardo Acierto, who at the time, had damning information about Michael Yang, a Chinese citizen who had been Duterte’s presidential adviser.

Then there were those diagrams alleging that journalists, media groups, a lawyer’s group, the Liberal Party, and Magdalo Party were all working together to oust Duterte. (LISTEN: PODCAST: Duterte’s diagrams and his war vs critical media)

Many of those named happen to be vocal critics of the President. But sports personalities who were never political were also included, prompting derision over the credibility of the President’s “intelligence” sources. Members of the intelligence community have distanced themselves from these “ouster plot” diagrams.

But because the diagrams came from Duterte himself, his supporters believe the accusations hook-line-and-sinker – posing danger or loss of credibility to those named.

Listens to economic managers

But if there’s one aspect of governance Duterte is careful about, it’s the economy. Duterte wisely acknowledges his weakness here and submits to the expertise of his economic team, led by his childhood friend Finance Secretary Sonny Dominguez.

Dominguez, labelled by Palace insiders as “the voice of reason,” is among the few Cabinet members who can be frank, even pointed, with the President.

Duterte listened to Dominguez when he suggested a financial institution for soldiers, instead of Duterte’s initial proposal to lease military lands to corporations for funding.

He sided with Dominguez on the issue of lifting restrictions on rice importation, rather than with resigned Agriculture Secretary Manny Piñol.

Duterte used his sizeable political clout to push for major economic legislation and measures advocated for by Dominguez and other economic managers – tax reform, rice tarrification, Build, Build, Build, and a national ID system, among others.

Dominguez credits Duterte with the record-low self-rated poverty incidence in a Social Weather Stations survey in the first quarter of 2019 and the highest investment grade the Philippines has ever scored, BBB+ from Standard & Poor’s.

The times Duterte pushed back against his economic managers was when populist measures were on the table. Despite their arguments, he greenlighted the free public college education law and P1,000 pension hike for senior citizens.

Touch for the masses

For all Duterte’s spurious moves, he excels in one thing: making ordinary Filipinos feel he cares.

It’s not just the populist laws and policies he has signed and carried out. His is a responsive presidency that flies to the side of typhoon victims, victims of major bus accidents, wounded soldiers, and maltreated migrant workers.

His is a “sincere, selfless leadership,” Trade Secretary Ramon Lopez told Rappler.

“Look at the reforms being made, or solutions or changes being made to address issues immediately…People can see his sincerity to serve and solve issues,” Lopez added.

Here is a president who fired Philippine Health Insurance Corp (PhilHealth) officials over a scam involving taxpayers’ money. Here is a president who threatened water management officials after homes run dry for weeks, never mind if his instructions don’t make sense.

Here is a president who would go to war against powerful Canada because it had the gall to dump garbage in the Philippines.

“A lot of his measures are things that ordinary Filipinos feel and I think that was what Filipinos were looking for in 2016; that’s what they’re getting until now,” said Aries Arugay, a political science associate professor at the University of the Philippines.

Filipinos are further impressed by Duterte’s determination despite seemingly insurmountable obstacles and interests of other powerful groups. In pro-Duterte blogger Dayag’s words, “walang sinasanto (there are no holy cows).”

Arugay cited the Boracay closure. “Everyone was like, ‘this is not going to happen, that’s not possible given the economic interest in that island.’ But it did happen.”

Likewise, people thought free public college education was an “impossible dream.”

“He was simply able to communicate to the people that the [term] political will that has already been abused, this is not just rhetoric. It seems like what the Duterte administration really wants, it gets done,” said Arugay.

Duterte even cleverly got tycoon Lucio Tan to send Philippine Airlines planes to Kuwait to bring home hundreds of standed OFWs. Tan, one of the “oligarchs” Duterte initially threatened and even accused of being part of a destabilization plot against him, was promptly forgiven.

Other small things reinforce this image – his gum-chewing at meetings with world leaders, his rolled up barong and jeans, his supposed preference for canned sardines over pricey banquet fare.

This is a President who will do things his way and as long as he helps the poor with the same type of determination, his supporters don’t want him to change.

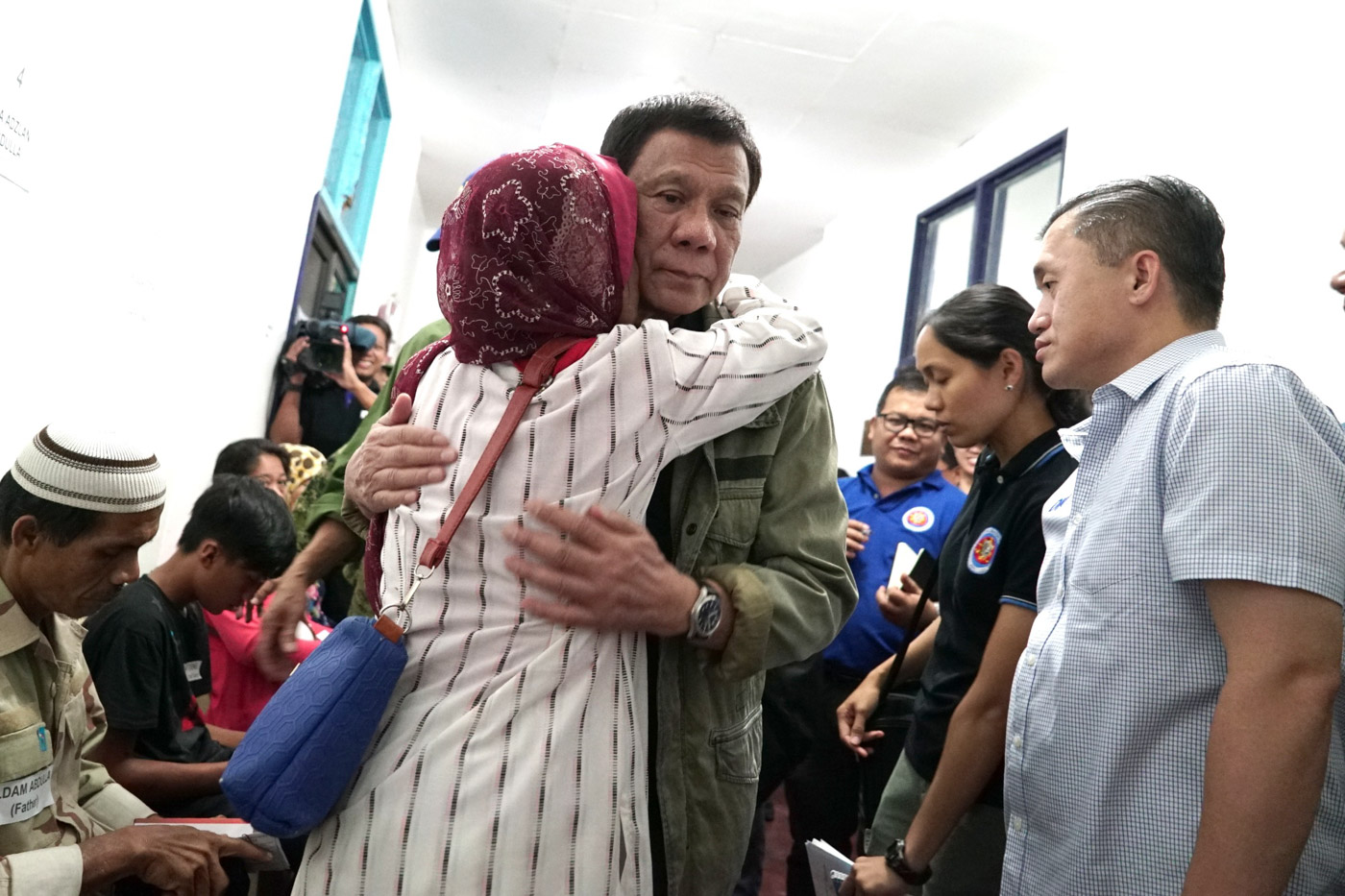

‘TATAY DIGONG.’ President Rodrigo Duterte comforts the kin of one of the victims who died during the car bomb attack in Lamitan City, Basilan on July 31, 2018. Malacañang photo

Two things could have threatened or can still threaten Duterte’s pro-poor image.

Inflation in September 2018 pulled down Duterte’s survey ratings. Global factors and some economic policies, like the rice tarrification law, which Duterte pushed for, softened the blow a bit and eased inflation.

Arugay said if inflation continued to worsen, Duterte’s numbers would have continued to dip. Presidents typically score low in “controlling inflation,” based on SWS presidential report cards since the Cory Aquino administration.

Inflation hits the poorest classes D and E the hardest. Filipinos from this economic class make up the majority of the population and are thus the grouping that politicians woo.

But as the first half of the Duterte presidency was about to wrap up, another controversy threatens to hurt the Chief Executive’s image as man for the poor.

The Recto Bank incident, messily handled by the Cabinet and dismissed by Duterte himself, involved 22 Filipino fishermen – the very definition of poor and marginalized.

While none of them died, their boat was hit and sunk by a Chinese ship, causing them to flounder at sea for hours before help came.

Instead of outrage at the Chinese and words of comfort for the fishermen, Duterte hid behind uncertainty saying an investigation is needed to determine what really happened. It’s a response that could have come from a typical bureaucrat.

Can most of his supporters explain this seeming lack of resolve from a President they have hailed for his political will?

Or will the contradiction gain traction and challenge his vaunted image as protector of the poor, exploited Filipino?

Unanswered questions

There remain controversies for which Duterte is yet to give a satisfying explanation.

If his drug war is so tough, why is he so soft on billions’ worth of shabu smuggling? Rather than kick out officials allegedly involved in the scam, he has merely transferred them to a different government post. Former customs chief Nick Faeldon and Isidro Lapeña come to mind. There’s also Allan Capuyan, accused of facilitating the entry of shabu, who is now indigenous peoples commission chief.

Why protect Michael Yang despite reports of his links to illegal drugs?

If his drive against corruption is serious, why recycle officials who allegedly committed such acts, and why threaten the Commission on Audit, whose task it is to spot abuse of public funds?

If he is all for freedom of expression, especially his own, why threaten media groups and journalists?

If he is determined to pursue an independent foreign policy, why pander to China?

These anomalies in his governance threaten to mar what legacy he’ll leave when he steps down in 2022.

No one gets through the presidency unscathed. The Duterte we see today is gaunter, grayer, more exhausted.

“There will always be a time to fade. I may be the more brighter than the lights here shining as President, but I will grow dim 3 years from now,” Duterte said on June 8.

But in most ways, Duterte has stayed the same. It’s the “constancy” of his political style that has kept his ratings high.

The next 3 years will be a question of how besotted Filipinos will remain with his brand of leadership or if future controversies will challenge the narrative that has served him so well. – Rappler.com

See more of Rappler coverage – news, in-depth stories, analysis, videos, and podcasts – on Duterte’s halfway mark here.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Just Saying] Diminished impact of SC Trillanes decision and Trillanes’ remedy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/Diminished-impact-of-SC-Trillanes-decision-and-remedy.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=273px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] Son of a gun!](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/newsletter-duterte-quiboloy.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=450px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[The Slingshot] Alden Delvo’s birthday](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-alden-delvo-birthday.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=263px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[EDITORIAL] Ang low-intensity warfare ni Marcos kung saan attack dog na ang First Lady](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/animated-liza-marcos-sara-duterte-feud-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=294px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newsstand] Duterte vs Marcos: A rift impossible to bridge, a wound impossible to heal](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/duterte-marcos-rift-apr-20-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=278px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.