SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

Can you imagine the day when cash is obsolete and Filipinos use only their mobile phones to pay for everything, even the most mundane stuff like a jeepney ride or street food?

It may seem like a scene straight out of the Netflix show Black Mirror, but it’s no longer science fiction.

In China, cash is considered almost dead. Mobile payments have become so ubiquitous that even beggars are collecting handouts by apps.

The country’s e-wallet giants, Alibaba-backed Alipay and Tencent’s WeChat, have 700 million and 1 billion monthly active users, respectively. That covers almost the entire China population, and a chunk of those numbers came only in the past 5 years. For comparison, Apple Pay, which comes pre-installed on every iPhone, has only 127 million users globally.

The Philippines hasn’t come close to the dizzying adoption that China has seen (to be fair, though, probably no other country in the world has).

Cash still accounted for 99% of local transactions as of 2018, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) earlier said.

A poll by data insights company TheNerve confirmed that cash remains the preferred payment mode of Filipinos.

On top of that, only 1.3% of Filipino adults own electronic money accounts, according to the BSP’s 2017 Financial Inclusion Survey.

BSP’s own data pegs e-wallet accounts in the country at about 12% of the adult population.

If we go by industry players’ claims, here’s how many e-wallet users we have:

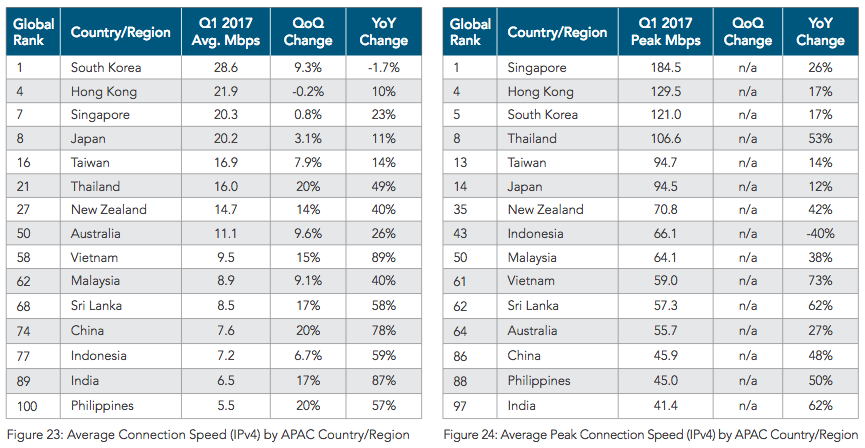

- Globe Telecom’s GCash: 20 million users as of February 2019 (bulk or 15 million of that number was recorded only in 2018)

- PLDT’s Smart Money and PayMaya: 8 million users combined as of December 2017

- Coins.ph: 5 million users as of May 2018

(Stats on other players are hard to come by.)

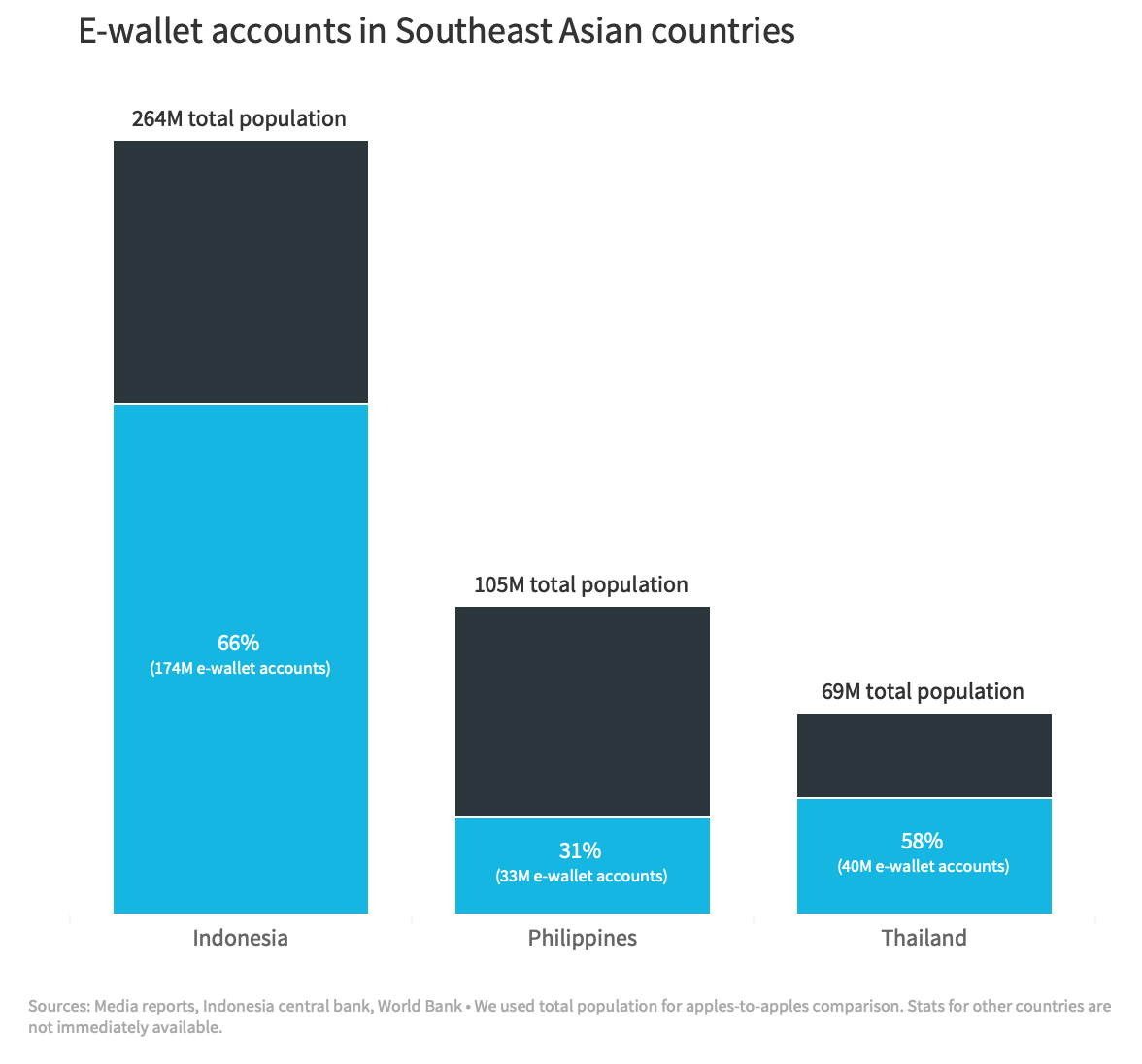

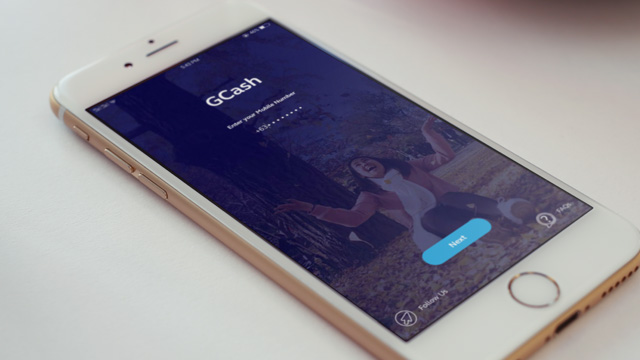

The sum of those figures translates to just over 31% of the total population and this is how it compares to some of the Philippines’ neighbors:

China’s e-wallet success will be hard to replicate elsewhere, but there are many lessons that can be drawn from its experience. While the Philippines was slow to adopt mobile payments in the past, it’s likely reaching a tipping point, especially as Alibaba and Tencent export their expertise and technology here via their strategic tie-ups with GCash and PayMaya.

China was uniquely primed for mobile payments

For context, mobile payments leapfrogged in China because of insufficient banking infrastructure. The size of the country and its population meant consumers had to contend with long lines in city branches and long journeys to those in the countryside.

Credit card usage was also low, partly because America’s Visa and Mastercard – and many other international firms – were banned in the Middle Kingdom. Mobile apps became a convenient way to transfer money and pay for goods and services.

Widening internet and mobile phone penetration, and rising incomes were also prerequisites. China’s smartphone market took off when cheaper Chinese alternatives to the iPhone and Samsung Galaxy began to sprout. Today, smartphone adoption stands at 63%, while cellular subscription is 104 per 100 people in the country.

The Philippine market’s fundamentals are quite similar to China’s early days. While the local market isn’t highly protectionist like China – and Visa and Mastercard are the two dominant credit card companies – cards have not seen that much take-up. It’s hard to get approved for a credit card if you don’t have any credit or banking history. With 77% of Filipinos unbanked, mobile payments offer the perfect case for people to sideswipe the plastic.

Like China, the Philippines has a rising middle class and is touted as a mobile-first market, with smartphone adoption at 59%, thanks to affordable phones – a lot of which are made by Chinese brands themselves. Cellular subscription is at 110 per 100 people.

Filipinos also spend the most time on the internet and social media among countries in the world. Facebook is practically their internet.

As consumers become digitally savvy, they begin to browse and purchase goods and services online and on-the-go.

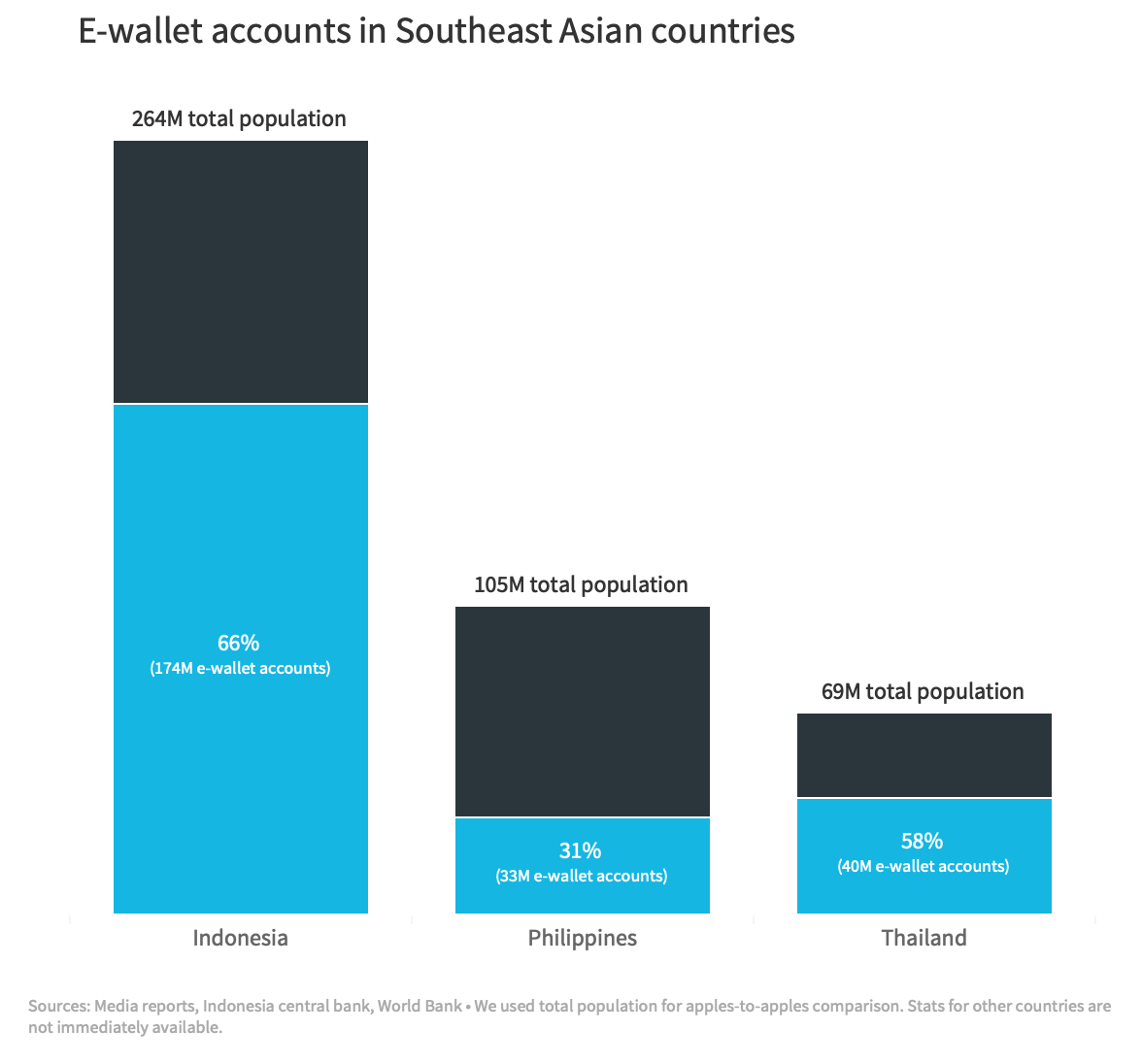

One roadblock perhaps is the country’s slow internet speed. It’s hard to create the habit of paying for goods anytime without a constant, stable connection, particularly in rural areas.

Though the speed has improved, it still lags behind other Asia-Pacific countries. That can be blamed on a lack of internet infrastructure.

Creating the habit of mobile payments through strong use cases

To boost the user count of its eBay-like e-commerce platform Taobao, Alibaba in 2004 launched Alipay, which held payment in escrow until buyers received their online purchase. Providing users with a go-between and guarantor catapulted Taobao to massive popularity. Alibaba, which also owns business-to-consumer marketplace Tmall, is China’s most prolific e-commerce firm – the one responsible for the world’s biggest shopping holiday known as Single’s Day or 11.11.

About a decade later, the escrow service was spun off as a separate company called Ant Financial to consolidate Alibaba’s various finance activities under one roof. Ant began to run mobile wallet Alipay as one of its units. By that time, Alipay already had a large user base.

Since then, Alipay dominated roughly 80% of mobile payments in China, where 75% of online sales were expected to happen through smartphones by 2018.

Till Tencent’s WeChat Pay entered the picture. If e-commerce was the driving force behind Alipay, WeChat Pay’s main weapon was social interaction.

The payments service is integrated into the WeChat social app and responsible for all the transactions happening there. It launched riding on the back of China’s longtime tradition of gifting cash-stuffed red envelopes. On Lunar New Year in 2014, WeChat allowed its users to send a virtual version of the red envelopes to fellow users. The app quickly became a key method for people to send money to each other.

That same year, WeChat made a big e-commerce leap by allowing any merchant – not just well-known retailers – to set up storefronts in its app under an open platform strategy. To defend its turf, Alipay followed suit.

The rivalry only grew from there. The next battleground was China’s online-to-offline market (i.e. offline services being booked online) which saw the firms include a gamut of services into their apps. You name it, they have it: ride-hailing, food delivery, movie-ticket buying, etc. Payments were the glue that held their ecosystems together.

By 2017, the firms had split the payments market: Alipay had a 54% share, while WeChat had 40%.

They had become lifestyle “super apps” embedded in Chinese daily life.

WeChat boasts of an unrivalled 1 billion active users network in China (to this day, Facebook has failed to leap over the Great Wall). The social aspect made it a lot stickier than Alipay and brought strong network effects, allowing it to catch up fast. The more users WeChat got on board, the more people wanted to join to be connected with their friends and families. And with more users came more sellers.

The Philippines, however, has no homegrown brand as powerful as WeChat or Alipay that could spark that kind of awareness about mobile payments among Filipinos.

The SIM-based payments services of Globe and PLDT (GCash and Smart Money, respectively) have been around since the early 2000s and the app versions (GCash and PayMaya) came starting 2012. Yet as of 2017, 40% of banked Filipinos were still unaware of electronic payment methods, according to the BSP Financial Inclusion Survey. That could partly explain the slow pace of adoption in previous years.

Apart from lack of awareness, security is another concern.

In TheNerve’s recent poll, most survey respondents said they don’t use mobile apps to pay.

Most think mobile app payments are unsafe and that their money and personal details might get stolen.

But of course, security concerns may have more to do with Filipinos’ inherent distrust of new financial technologies than the apps themselves (transactions with the top apps have proven secure thus far). The country has seen countless fraud incidents like ATM card skimming and online scams. So you can’t deny the appeal of dealing with a person – there’s someone to hold liable if the transaction goes wrong.

E-commerce is a booming Philippine sector, posting a 42% surge in gross merchandise volume from $500 million in 2015 to $1.5 billion in 2018, according to a Google report. It’s expected to grow to $10 billion by 2025.

Despite this, cash-on-delivery is still the number one way to pay for online purchases – similar to how China’s market started before Alipay was introduced. The escrow service was a game changer for China, specifically Alibaba’s Taobao, assuring users that they wouldn’t get cheated on the platform.

In the Philippines, regional players Lazada – which was acquired by Alibaba in 2016 – and Shopee have been in a neck-and-neck race. Lazada’s payments feature, HelloPay, has merged with Alipay and rebranded to the latter.

However, the companies said at the time that HelloPay’s features would be unchanged. It doesn’t seem like Lazada has adopted Alibaba’s escrow service, but it would help build trust among Filipino shoppers and push them into the habit of online payments if this happens.

Local payments players will have to work much harder to hook consumers. These days, that means ads and integration with massive platforms like Facebook, cashback and other promos, as well as strong use cases.

The marketing efforts will entail high cash burn, so players need substantial backing to last in the battle.

Alibaba’s Alipay and Tencent’s WeChat play a key role, as they take their fight for dominance to other markets. Both have bankrolled their international expansion not just by targeting globe-trotting Chinese consumers, but also through investments in local markets.

Alibaba affiliate Ant Financial (parent of Alipay) has made a major infusion in GCash’s parent Mynt and Tencent in PayMaya owner Voyager Innovations – both moves mean deeper know-how and capital to kick off the local apps’ aggressive growth.

GCash and PayMaya started out with their telco groups’ core product – phone credit top-up (this made sense since the Philippines is a largely prepaid telco market) – money transfer, and bills payment. Now they’re gung-ho developing their own ecosystems of services.

Other players with huge investor backing have also launched their bids to replicate China’s success.

Ride-hailing company Grab has introduced GrabPay. Coins.ph, a blockchain-based e-wallet, has been acquired by Indonesia’s Go-Jek, Grab’s archrival that has its own payments feature called Go-Pay. Grab and Go-Jek are racing to become Southeast Asia’s leading super app that offers everyday services on-demand.

All these companies have been flooding the market with promos to capture users.

Here are some top e-wallet use cases, based on TheNerve’s survey:

Here’s the breakdown of e-money payments by key use case, as per BSP data:

QR codes are the way to go

China’s tech giants are battling not just for online payments, but also offline transactions.

Mobile wallets can’t win users if merchants don’t accept this kind of payment in-store. This is something that Alibaba and Tencent knew very well, so they’ve been slugging it out for brick-and-mortar shops, restaurants, and other offline outlets.

They understood early on that sellers located outside cities might not be willing to accept mobile payments that would require them to shell out a big amount and upgrade equipment. In the US, many vendors had to migrate to payment terminals compatible with near-field communication tech or NFC to accept Apple Pay and Google Pay.

The QR code is a black-and-white, two-dimensional barcode that stores data in codified format and can be read by a scanner or the camera of any mobile device. It’s a way to skip the step where the payer and payee’s account details must be inputted for a transaction to go through. The system is way cheaper than NFC and the traditional point-of-sale (POS) terminals or cash registers. Merchants in China could purchase a QR code scanner – commonly referred to as the “little white box” – for a quarter of the price of handheld POS terminals.

Merchants without scanners can just print out a QR code that consumers can scan using their phones to pay. This means anyone can become a merchant since hardware isn’t necessary.

It also means faster checkout time – no need to count bills and coins. Soon enough, QR code payments began taking China’s offline stores by storm.

The technology has reached Philippine shores, raising the prospects of mobile payments finally taking off among vendors. A few months after Ant Financial’s investment in 2017, GCash introduced QR code payments. Not to be outdone by its competitor, PayMaya launched the feature on the same day.

Before 2017, both e-wallet providers offered Visa and Mastercard prepaid cards that their users could use to pay at physical stores. So essentially only merchants with card terminals were able to accept the payments. The SIM-based mobile payment service, on the other hand, involved sending a text message with the amount and store’s code to a 4-digit access number.

Lower fees are encouraging

Another factor that should drive faster adoption of mobile payments is lower fees. In the US, Apple Pay and Google Pay don’t store money – instead, they work by charging directly to credit cards linked to the apps (the US is largely a card-based market). So it means those card firms take a percentage of each transaction from merchants.

Alipay and WeChat are undercutting those card companies by giving users the ability to pay using their app balances, which can be sourced directly from bank accounts. This doesn’t mean no charges for merchants, though. Alipay takes a commission of 0.6% on sales, but that’s far lower than credit card commissions, which run between 1% and 5%.

GCash and PayMaya work the same way as the China e-wallets, charging competitive rates. Both offer cash-in through physical stores. GCash alone offers the option to link and unlink bank accounts within the app.

Users can also top up both GCash or PayMaya via the InstaPay option offered by banks. InstaPay is an electronic fund transfer service initiated by the BSP that allows people to transfer money almost instantly between accounts of participating BSP-supervised banks and non-bank e-money issuers in the Philippines.

While going through InstaPay admittedly adds another step (users have to log into their bank app first), being able to wire money online and instantly will prove handy for consumers.

InstaPay is one of the two automated clearing houses (ACH) for electronic fund transfers set up by the central bank under the National Retail Payment System. The aim is to promote interoperability among industry players so consumers can easily transfer money across different financial accounts.

| InstaPay |

|

| PESONet |

|

The BSP has been one of the most progressive regulators globally when it comes to promoting cashless transactions.

It employs a test-and-learn regulatory framework where players are relatively free to innovate.

Among the things the central bank has allowed are:

- For non-financial institutions like GCash and PayMaya to issue e-money

- For remittance agents, mostly sari-sari stores, to conduct cash in/cash out via mobile payment apps

- For know-your-customer screenings to be conducted online or via digital means

Will we ever get rid of cash?

Clearly, the BSP sees the benefits of going cashless. Cash is costly to handle – you need to employ people to count, store or transport it, hence the fees banks charge consumers. It can also be dangerous to carry around.

On the other hand, mobile app payments are quick and easy to scale, which translates to lower fees. They’re also transparent, as transactions are recorded electronically and can be tracked.

With lower fees and simple know-your-customer procedures, the poor and unbanked could participate more broadly in the financial economy through the apps. What’s more, the apps provide a way for low-income households to save for emergencies and other needs, and for small businesses to access capital to grow.

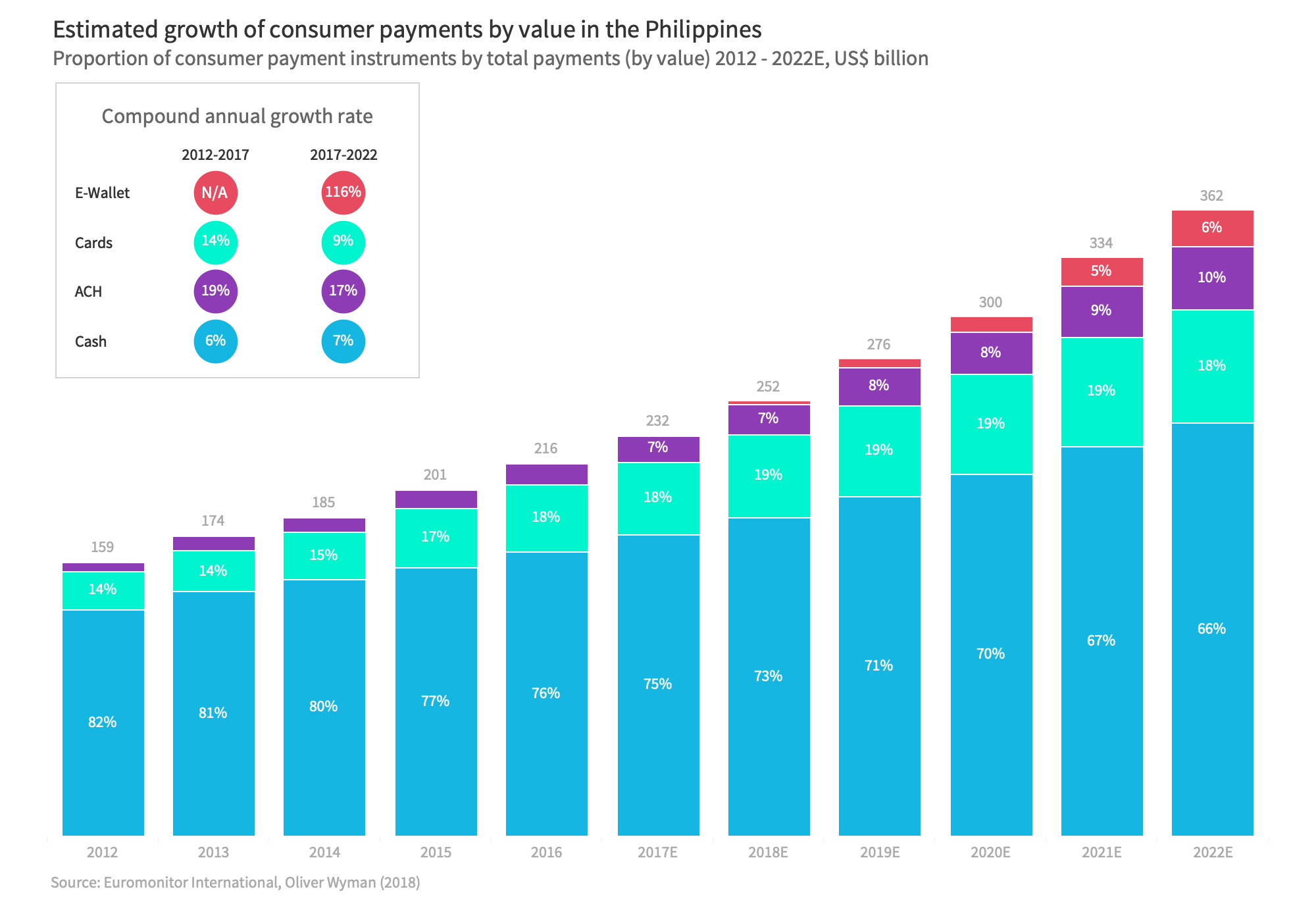

That’s why the central bank is doing its best to pave the way for a cash-lite society. It may be some way off, but experts believe the Philippines is on the cusp of a digital payments revolution. The BSP itself is optimistic that digital transactions could surge to 20% of total local payments by 2020.

Still, there are headwinds along the way. The promise of eliminating cash takes away the anonymity of every single transaction made. This is expected to be met with strong resistance from unscrupulous parties.

It also brings about unsettling worries among consumers, given that volumes of their data are controlled by a few tech companies.

With the vast amounts of personal information and transaction histories on Alipay, its parent Ant Financial has developed a proprietary platform called Sesame Credit, which calculates people’s credit scores based on that data. Ant then uses those scores in extending loans to consumers who are otherwise ignored by banks.

China has a grand plan to implement a social credit scoring system that would judge its citizens’ behavior and trustworthiness. Concerns abound that it could access tech firms’ data, though the companies assert they won’t release it without users’ consent. A bad score could mean the loss of certain rights, such as boarding flights or riding the train.

Again, it’s eerily reminiscent of the show Black Mirror, but that’s how the future may really be shaping up.

To be concluded: Part 2 | Coins, GCash, GrabPay, PayMaya: Who’s leading the PH mobile payments war?

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.