SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – In post-war Manila, when people wanted to be entertained, they flocked to places like the Manila Grand Opera House, Teatro Zorilla or the Clover Theater to witness a hodgepodge of comedy skits, song and dance numbers, gymnastic feats and magic acts.

These were performed live every night until the wee hours of the morning by a band of dedicated artists who were paid Php 3-4 a night or sometimes not paid at all. This worked just fine in the halcyon days of the the stageshow, an art form of Philippine theater that survived well into the 1960s. Some of its artists were able to cross over to the mainstream:

- Elizabeth Ramsey sang with a 26-piece band, and while traveling from town to town to sing at fiestas, she slept on the floor of the truck that transported them

- Bayani Casimiro started as a clown and comedian before becoming known as the Fred Astaire of the Philippines

- Before he became the Master Showman of Walang Tulugan, German Moreno was a telonero and sold peanuts and watermelon seeds at the Clover

- Dolphy, formerly known as Golay, was a dancer at the Orient Theater during the Japanese Occupation

The others were not as lucky. When entertainment retreated into the television sets blaring in living rooms, live shows fell out of fashion.

The fate of these forgotten artists is what drove Mario O’Hara to write the script to Stageshow. Tanghalang Pilipino’s Artistic Director Nanding Josef first read the script 3 years ago and found it moving. He asked O’Hara why he wrote it.

O’Hara said: “I wanted to document what I personally know and witnessed.”

Josef was not surprised that O’Hara was inspired by real life. After all, O’Hara claimed that his masterpieces, like the love triangle in Insiang or the cemetery dwellers in Babae sa Bubungang Lata, were based on what he saw in the slum area outside the village where he lived in Pasay.

Josef explains the allure of what Stageshow is all about: “The lives and loves of the vaudeville and stage show artists. They were highly skilled and gifted. But like many of us contemporary artists, unlucky in love and money.”

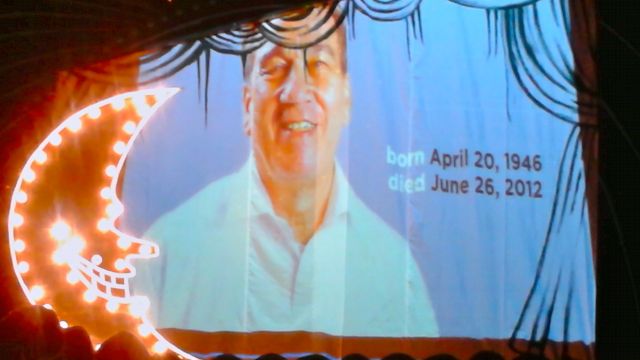

O’Hara seemed intent with documenting the lives of these artists. What Josef didn’t know was that O’Hara was ill. While readings and rehearsals started earlier in the year, O’Hara never saw the staging of his play, as he passed on in June of this year.

Stageshow is Mario O’Hara’s tribute to bodabil’s raunchier vagabond cousin.

Director Chris Millado chose to set it in the 1950s, a time when the “country was still largely a peasant society,” one on the cusp where live shows are on the wane as television took its place.

The show’s opening number “Mambo Magsaysay” by the Tres Dahlias harkens back to a Philippine Golden Age.

The mambo was decadent for its time. Its use as a campaign jingle of then-presidential candidate Ramon Magsaysay marked him as the modern and hip choice. The titillating trio of Ester, Chabeng and Magdea were women confident of their sexuality. Chabeng (played by Angelina Kanapi) is a seductress, the Babaeng Gagamba who lured and devoured as many men as there are islands in our archipelago. Magdea had a gift of magic hands which alternately pleasured anonymous men in darkened theaters and later miraculously healed the legs of Ester’s crippled grandson Nonoy.

Which brings us to the last of the Tres Dahlias: Ester, whose love story with the debonaire conductor Tirso we follow all the way through.

When she tells Nonoy the story of How I Met Your (Grand)Father, it is a rich exchange full of double entendres, starting with the “For Rent” sign plastered on her bum. The palpable chemistry between leads Shamaine Centenera-Buencamino and Nonie Buencamino is a delight to watch.

If Ester plays the martyr, Tirso as essayed by Buencamino hits the right notes of rakishness and bravado. He is master of the manor, as in “Wen Manong,” where the rules of the household are also the rules of manhood that fathers pass on to their sons: Wives can only shine shoes and iron their husband’s clothes. The wives had no voice or right to complain.

Ester had her suspicions of Tirso’s affairs, which manifest themselves in her dreams.

But Tirso pays to heed to his wife’s fears, and goes off in the afternoons for rehearsals with his band. He is, after all, its conductor. This leads to the number “Tittina, My Tittina,” where Tirso plays each lover as a musical instrument: the guitar, the viola, the piano, the drums. The orchestra of women are mostly pretty young women in the chorus, but also includes Chabeng.

The affair would only be confirmed after Tirso has abandoned Ester, who later confronts Chabeng in the perya where she plays the Babaeng Gagamba. But Tirso has also disappeared, and all Chabeng has left are his clothes. Chabeng asks for Ester’s forgiveness (“I Apologize”) and offers the consolation of a lead to Tirso’s whereabouts.

Rumor has it that Tirso suffered a stroke and was last seen roaming the streets as a beggar. This sets Ester on the quest for her missing husband.

Tirso once made time move forward when they first had a baby and were truly happy; now Ester would do the same and hop from town to town in search of her lost love. Ester gets lost, and robbed of all her belongings, ends up in a plaza near naked and shivering in the rain.

A beggar (Lou Veloso) takes pity on her. He gives her a blanket and cheers her up with a little magic show. Only for it to take a bizaare turn when he forces himself on her. “We think nothing of dogs who mount each other on the streets,” he declares. “It is only humans who give it malice. You are here in the streets, roaming. If you’re human, you wouldn’t be here.”

Then Veloso’s beggar hums Chaplin’s “Smile” as he walks away from the scene. Perhaps even more disturbing is that the rape is never mentioned again. It was something that happened, just another station of suffering on Ester’s way of the cross.

After picking up what’s left of her clothes and dignity, Ester runs into another beggar, wheezing and hungry. She gives him food, and then recognizes the man for who he is, the treasure of a man she calls her husband.

It’s interesting to examine the fate that befalls the two leads. Tirso had it coming: He was a womanizer, suffered a stroke, became a beggar and later attempted suicide by jumping off a bridge. And yet, all that was erased in the end by an act of kindness from Ester.

He dies in the end, yes. But he could go in peace as all was forgiven.

Ester, on the other hand, was the epitome of selflessness. She gave Tirso everything she had, and had everything to lose. Tirso’s death brought together the de facto family they had: the child they took in and gave up, the other children they adopted, the friends from their stage show days. Perhaps the suffering was worth it.

Musical director Jeff Hernandez’s choice in using some of the most recognizable songs from the era succeeds in giving the play a touch of authenticity. I have it under good authority that Rody Vera’s performance of Bobby Gonzales’ “Ikaw Ang Mahal Ko/Hahabol-habol” is pitch perfect.

Also touching was Tony Casimiro’s fiery tap dancing through a faster and larger score.

For those who grew up with the music, it was like being transported back to Grand Opera House for an afternoon or evening when the musicians themselves played it over live radio. To those who came too late to the party, Stageshow stirs a curiosity to discover music whose only memory and familiarity come from listening to their (grand)parents’ plaka.

If only for this continued curiosity, the music and people from the stage shows are allowed to live on, even after the curtains are lowered and the kleig lights are dimmed inside the empty theaters. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.