SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – As a countryman unknown to him, I was happy when I first heard about Cesar Apolinario’s venturing into cinema with his directorial debut “Banal,” which won for this seasoned journalist the Best Director prize at the 2007 Metro Manila Film Festival.

That film turned out less than anticipated (check out Francis Joseph Cruz’s review), but I was still happy to learn about Apolinario’s making public and fulfilling his aspiration as a filmmaker — the same solidarity felt by an entire nation whenever it roots for Manny Pacquiao, or for any compatriot who does remarkable work giving pride to the Filipino, the coolest race in Asia.

It’s always welcome news whenever Philippine cinema, our beloved cultural institution, gains one more advocate, especially one from outside its sphere, as in Apolinario’s case.

One also wishes that Philippine theater would also summon that many recruits, because this world is just as fascinating and colorful, and it deserves to be just as crowded with its share of aspirants. After all, during their reign over Philippine cinema, Nora Aunor and Christopher de Leon (whose successors might be Eugene Domingo and Piolo Pascual) also conquered the theater.

This drive towards versatility is evident in “The Dance of the Steel Bars,” Apolinario’s second feature which had its public screening on the historic date of June 12 — the same time the latest Superman franchise was shown in most cinemas.

Apolinario deserves praise for timing his film with “Man of Steel,” thus risking its obscurity before that icon of cultural imperialism from the planet Krypton. And “Steel Bars” was handicapped not only by Superman’s omnipresence in the theaters but also by the fact that not all SM cinemas showed this movie, as SM’s corporate empire should be obliged to.

At SM Megamall, the crowds that had gathered outside its cinemas might have evoked the fiesta spirit of the Manila Film Festival during its heyday in 1960s downtown Manila — a captivating milieu, also timed originally with Independence Day, that Nick Joaquin and Pete Lacaba dutifully recorded in their reportage on Pinoy pop culture and that would be recreated later on by the cinema of Wong Kar-Wai.

But inside Cinema 6, which showed Apolinario’s film, one is confronted by the chilling reality — because it was cold in this sparsely occupied theater — that time has turned over to its current tide, that nostalgia is denial of the present, and that the crowd one saw outside the Megamall theaters was actually queuing for “Man of Steel.”

Watch the ‘Dance of the Steel Bars’ trailer here:

This is the same Megamall that screened Fellini’s “8 ½” and Hitchcock’s “Rear Window” to SRO crowds in the late ’80s. We’re talking about cinema relics as they were re-shown 30-plus years ago.

Apolinario’s second feature can be regarded as an affirmation of heritage, that of Philippine cinema. Beholding the film’s exposition of life in the Cebu Provincial Detention and Rehabilitation Center, one is reminded that this film operates in Daboy (Rudy Fernandez) territory — wherein the outsider holds his individuality and his dignity amid the dehumanizing confines of prison, and its extension that is Philippine society.

Yet for all its filth and insidious atmosphere of violence, there is nothing in this picture that is as harrowing as the prison life one sees in Mario O’Hara’s “Bulaklak sa City Jail,” or in the grueling finale of Marilou Diaz Abaya’s “Alyas Baby Tsina.”

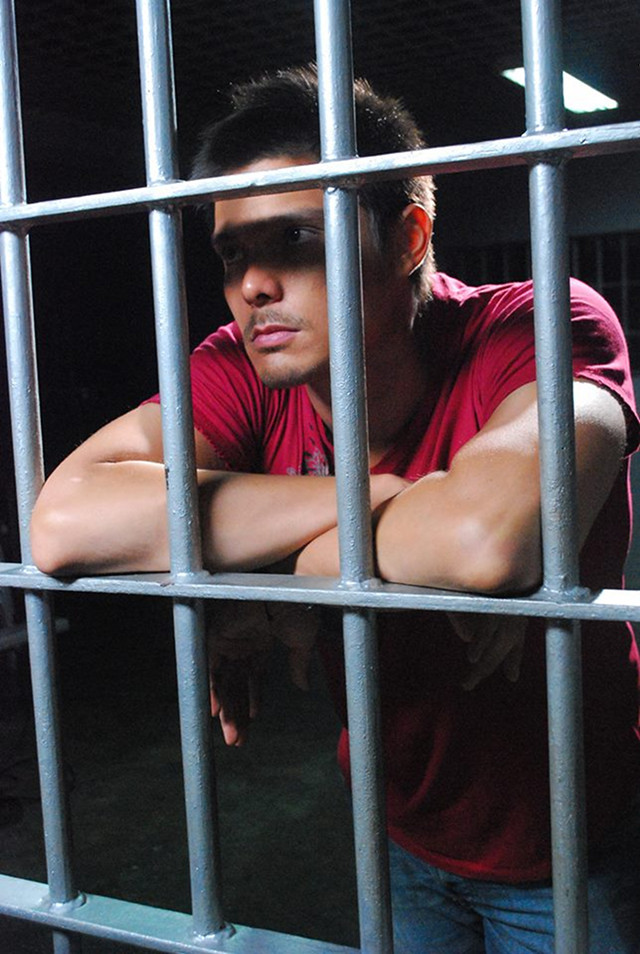

The solitary confinement endured, in one interlude, by Dingdong Dantes, Patrick Bergin and Joey Paras could have echoed the grimy horror of such detention as portrayed in “Baby Tsina,” to which its heroine (Vilma Santos) responds with a quiet, defiant fortitude — yet another striking facet of her long career with its comprehensive portrayal of the modern Filipina.

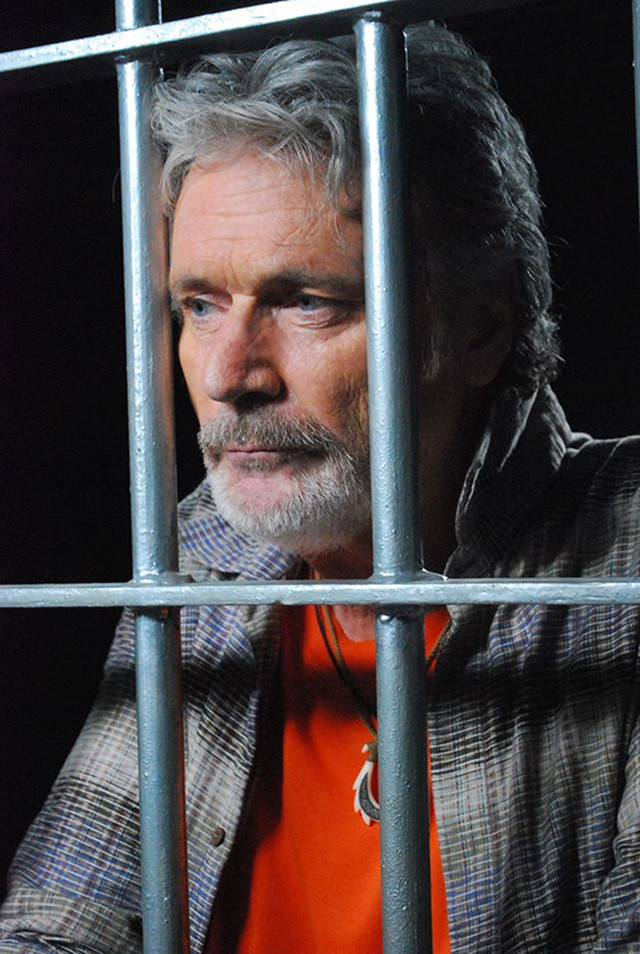

Dingdong Dantes and Patrick Bergin, the renowned Irish actor, convey that Vilmanian, shall we say, serenity, amid their harsh confines — which, however, doesn’t look too harsh in this film, when one beholds that beautiful frame of a cockroach in its slow crawl on the dim prison floor.

Bergin’s involvement in this project is one of its great enticements to any cineaste. Here, he plays an American (going by his accent) serving his sentence for a falsely accused crime. It’s an earnest performance yet also rather too relaxed, as if one were watching Hunter Thompson on a vacation in our penal system.

This viewer, at least, would have also wished that Bergin had been allowed instead to play the Irishman that he really is, considering the natural affinity with the Filipino people among the few Irish (mostly from the Catholic clergy) who have made the Philippines their home, even mastering the language of their adopted community.

The aura of menace that one gleans from Bergin’s finest work in Hollywood is missing in this film, or rather assumed instead by Dantes — who, like Piolo Pascual, is a keeper of the flame of the Christopher de Leon School of Acting, especially de Leon’s impeccable work during the ’70s and ’80s.

Watch behind the scenes clips and interviews with the cast here:

The complexity of a good heart impeded by stupid human impulses is plain to see in Dantes’ role, as a man sent to prison for literally bashing a gay admirer, conflicted by the machismo “values” of his father and the feminine nurturing of his mother from whom he developed his terpsichorean talent. What a problematic material, this part — yet it’s made somehow believable by Dantes, and by the visual scheme of the movie itself.

That montage of Dantes’ childhood to his tortured adulthood, for one, is truly worthy of the Jarlego family of film editors. The graffiti surrounding Bergin’s cell is another visual masterpiece, so expressive that one suspects it was really rendered by an artist. So are the prison courtyard scenes, which are lively to the point of recalling “Bagets,” Maryo J’s now-immortal masterwork from the ’80s. Ricky Davao (as the reformist warden) in shades evokes Gangnam Style. The hip-hop score is a sound painting by itself.

Then there’s Dantes’ tango number with Jon Paras (the flamboyant gay in this prison), which is a rom-com moment in an otherwise earnest film and the closest approximate to Dantes endeavoring a gay role.

These facets I single out, not to deride them at all, but to amplify the critic’s role, his extended participation in the creative process. For as a critic writes his appreciation, he is actually carrying on the creative life of an art work, this film in particular.

Criticism should never be guided by fault-finding but should function primarily as another department of the work in question. In the spirit of Shaw, all creative expression is valid, as any critic will find, who can also act, or make a movie or write a poem or play the violin. I play the piano a little, by the way. What I’m really saying is that this is a great film, all told — until Gwendolyn Garcia’s sudden-as-to-be-grand entrance, and in one stroke reforming Cebu’s prison system by her mere presence.

One can take the standard view that this film becomes a disaster at this point, as it slides into sly propaganda, evidently to acknowledge the Cebu governor’s hospitality to this project.

Yet one can also take the more enlightened appreciation, again, that the film properly ends at this point. What happens afterwards is something of a special feature if this movie were now a DVD package, with the prisoners staging their spectacular variety-show number to Garcia’s demure satisfaction.

This scene is a masterpiece because of its radical and even communist implication — as it exposes the dregs of society, its very lowest stratum, submitting at last to the kapritso of the oligarchy, akin to the gladiatorial entertainment of Ancient Rome. Garcia, then, should be truly commended for going this far in her support for this latest flag-bearer of advocacy cinema. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.