SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

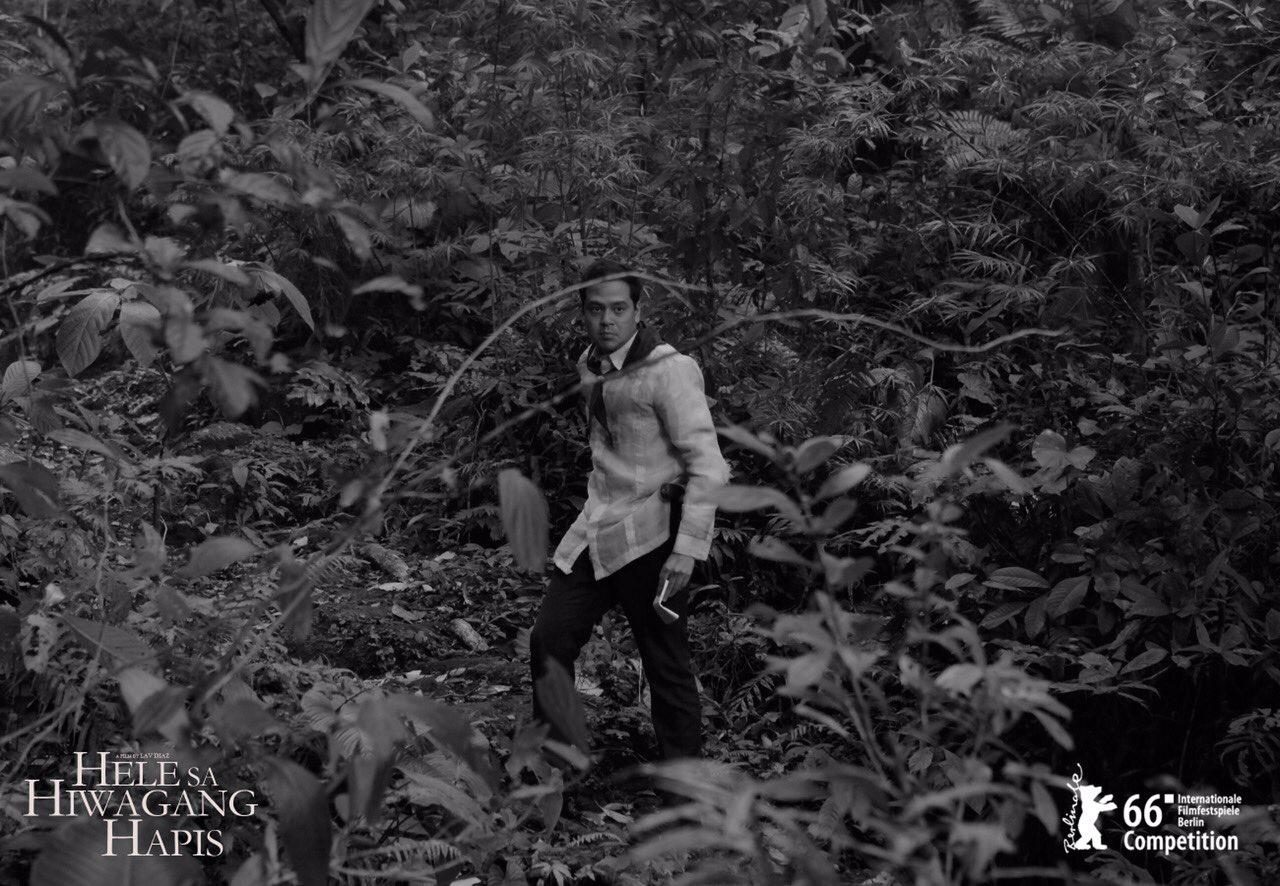

A love letter opens Lav Diaz’s Hele sa Hiwagang Hapis. A musician (Ely Buendia) is writing to Pepita about the impending execution of Jose Rizal. He also writes about his decision to witness what he refers to Spain’s crime against the Filipino people, to commit to his memory the pain of everything that has transpired that day. Right after finishing his letter, he strums his guitar, playing fragments of what would be the patriotic song whose endeavors are couched in sentimentality.

Another declaration of love ends the film. Gregoria de Jesus (Hazel Orencio) has just ended her desperate but futile search for the remains of Andres Bonifacio, her husband who was brutally murdered by fellow patriots.

She laments her harrowing experience, how her aimless wandering around the forest has exposed her to the veiled atrocities of humanity, how her fate and the fate of her husband emphasized the seeming void that is her struggling nation’s soul. She drifts away, desolate and hopeless. (READ: ‘Hele sa Hiwagang Hapis’ stars: Why you should watch ‘mesmerizing’ Lav Diaz film)

Meditation on love

Love is the crux at the center of the sprawling narratives of Hele sa Hiwagang Hapis.

The loyalty it fosters forces Gregoria to abandon the comforts of home for the tumultuous life her husband would lead as the head of the revolution.

The dedication it results in pushes her to the edges of sanity as she roams the forest to retrieve whatever remains of her beloved. Mang Karyo (Joel Saracho) and Aling Hule (Susan Africa) accompany Gregoria everywhere in near parental fashion, owing largely to their own backstories about their own failures in their respective passions.

It is the root of the irrevocable betrayal of Gregoria’s final companion in her impossible mission, Cesaria Belarmino (Alessandra de Rossi) whose illicit affair with the Spanish Captain-General (Bart Guingona) has resulted in the massacre of Silang. It brews wrath in the hearts that formerly housed romantic aspirations for the country, like the heart of Simoun Ibarra (Piolo Pascual) whose transformation into a nihilistic cynic is jumpstarted by the death of his Maria Clara, his muse; or of Isagani (John Lloyd Cruz), whose idealism for the country is thwarted by the rejection of Paulita.

Diaz’s 8-hour opus could be a meditation on love, on its permutations and defining role in the eventual formation of the nation. Hele sa Hiwagang Hapis, while set during the time of war, avoids bloody battles and action-packed skirmishes. Instead, it is populated with songs, stories, and poems, all of which are products of a culture that foments romanticism even in the midst of extreme strife and suffering.

The film submits a plausible suspicion that the nation that Diaz carefully molds as one of clashing sins and virtues is united by an unbridled passion for the affairs of the heart.

The art in suffering

The most apparent impression from Hele sa Hiwagang Hapis is that the birth of the nation is accompanied by an immense amount of pain and suffering. Diaz does open the film with a quaint statement of love, but that statement is bridged by the impending martyrdom of Rizal.

The film’s other characters are not afforded any luxury. They rest, but they rest to converse, to argue, to sow melancholy in their respective quests. Their journey is not only physically taxing, it is also emotionally and spiritually exhausting.

However, the film does not indulge in the plainness of pain and the bluntness of violence. It doesn’t fetishize torture or tedium. Diaz acknowledges that as a result of the country’s centuries of restrained ache is the proliferation of relevant artistry, in works whose nationalistic intentions are cloaked in song and literature.

Diaz celebrates that what might have sparked the revolution is not a singular thirst for an armed uprising but the sharp words of literary figure whose novels symbolized everything that is wrong in society. In the film, Diaz does not distinguish history from fiction, simply because in his mind, it seems both are interchangeable, with history being nothing more than fiction inspired by available facts, and fiction being nothing more than an ingenious incorporation of history into stories that originated from the imagination.

Hele sa Hiwagang Hapis borrows characters from Rizal’s famous fictional work and places them within the same setting that inspired their existence. At the same time, the film conjures myths and legends from the country’s pre-colonial past, primarily in the form of three tikbalangs in the shape of wily humans (Bernardo Bernardo, Cherie Gil and Angel Aquino), to take part in what is depicted to be a collusion of sinister forces that seek to trap the emerging nation within a purgatory of suffering. (READ:‘Hele’ from the other side: Cherie Gil’s Berlin film fest chronicles)

Stylized Diaz

Men from Rizal’s fiction, creatures from legends, and sorrowful icons plucked from the pages of our history books cross paths in Diaz’s intricate tapestry that depict a nation that is still reeling from the indelible pain of its birthing.

It is almost as if Diaz were implicating the country’s revered nationhood as part fiction, part myth, and part congruence of all of the past’s painful experiences – or simply, that there is both terrible and beautiful power in the collective imagination of the nation.

Hele sa Hiwagang Hapis is by far the most stylized of Diaz’s recent works.

There is meaning in the exquisitely gorgeous lensing of Larry Manda, who is partially free from the restrictions of the usually immobile and naturally lit frames of most of Diaz’s works. The costumes, the sets, the flowery dialogues and the seamless sound design all contribute to render the film as far removed from reality as possible, closer to the realm of literature as opposed to Diaz’s other more organic and spontaneous features, where immersion is the primary motivation for the immense length rather than narrative breadth and scope.

It is as if Diaz demands that the distinction between fact and fiction be fully felt, requiring that his film be acknowledged as a work without any pretensions of attempting to acquire any sensation of realism. It is a film, the same way El Filibusterismo is a novel, or tikbalangs are creatures of local legends. It is a product of inspiration and of imagination, with the same potential to inflict or deflect change the same way as all the fruits of other fertile minds.

Tainted revolution

In the scene where Isagani asks Simoun how to achieve freedom, Simoun rebukes Isagani of his close-minded concept of freedom, saying that “these days, it is clear that Filipino freedom is emancipation from Spain. But Filipino freedom is greater than that. Freedom requires long discourse. Filipino freedom demands exhaustive struggle. Being free from Spain is just the start.”

It is easy to digest Hele sa Hiwagang Hapis as simply an exploration of the past, limited to men and women who have died decades ago or characters who are but figments of rich imaginations. It is convenient to view it as a period piece that dazzles with the sheer conceit of its daring concept and the bravery of its daunting length.

Diaz however offers his film and its challenge as a starting point for treating freedom not as an element of a foregone and finished history, but as a continuing struggle that everyone is still a part of.

Rizal crafted both Simoun and Isagani as symbols of cynicism and idealism. Diaz stretches Rizal’s characters by extending their stories with youthful Isagani carrying the burden that is Simoun through the forest. Simply put, there is no end to the struggle, the same way that there is no way of erasing the sins of the past. The task at hand is to keep on venturing forth, even while dragging all the boundless weight of a nation’s inglorious history.

There is no greater love than to selflessly endure such a burden, even with all the anger, shame, and sadness that is part and parcel of being sons and daughters of a revolution tainted by rape and betrayal. – Rappler.com

Francis Joseph Cruz litigates for a living and writes about cinema for fun. The first Filipino movie he saw in the theaters was Carlo J. Caparas’ ‘Tirad Pass.’ Since then, he’s been on a mission to find better memories with Philippine cinema. Profile photo by Fatcat Studios

Francis Joseph Cruz litigates for a living and writes about cinema for fun. The first Filipino movie he saw in the theaters was Carlo J. Caparas’ ‘Tirad Pass.’ Since then, he’s been on a mission to find better memories with Philippine cinema. Profile photo by Fatcat Studios

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.