SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

A girl stares curiously at the sky.

The sun is shining, but rain is pouring. Her grandmother tells her that the sky is weeping because two tikbalangs, supposedly oblivious to love, are getting married. She heads out to a nearby park and actually witnesses the mythical creatures that are cursed to be strangers to romance

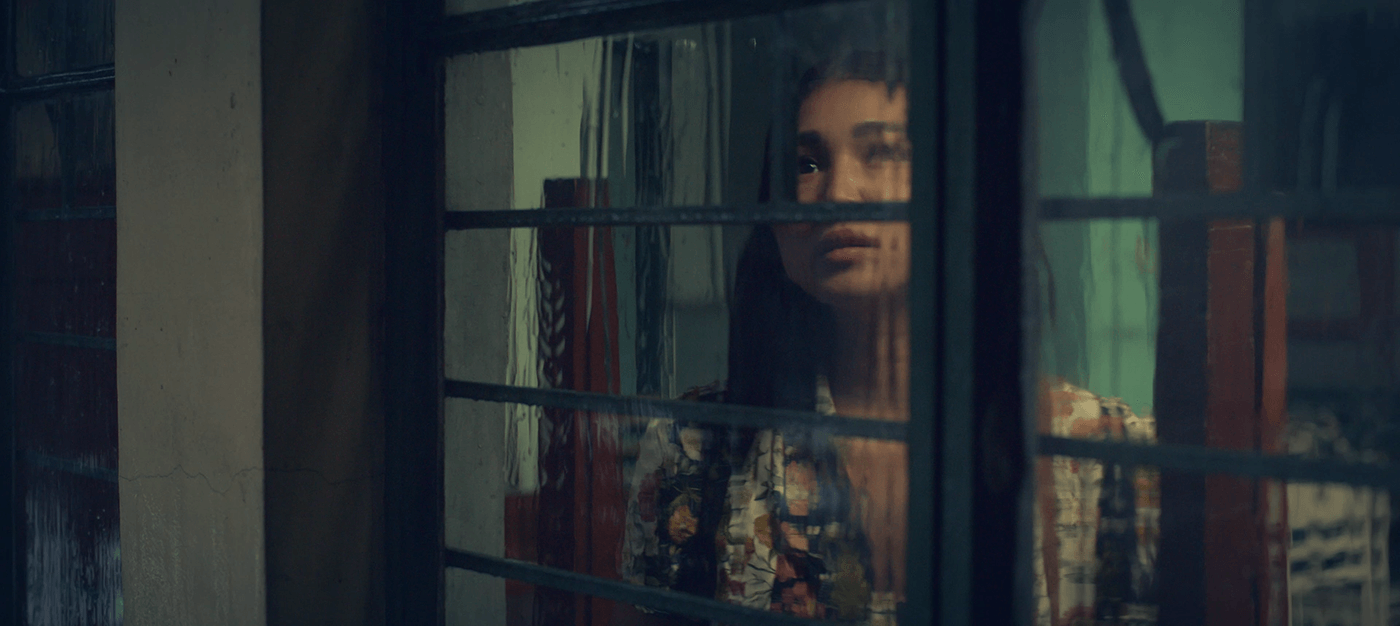

The same girl, now a lovely woman, excitedly heads out of her house despite the pouring rain.

She arrives at the house of the boy she has waited for years to love. When the boy finally invites her in, he introduces her to his wife who is carrying their baby. That rainy moment, she who has all the right in the world to love unlike the tikbalangs she once witnessed in their moment of bliss, has her romantic dreams fall apart.

Loose but profound connection

There is a loose but profound connection that Irene Villamor elegantly establishes between the imaginative girl whose fantasy gets their fairy tale ending and the beleaguered woman whose reality is to have her fairy tale ending dissipate into nothing.

Ulan lures its audience with the promise of a love story that goes by way of a woman struggling to find happiness by finding a man to love her for who she is. It, however, pushes for more. It explores the mind and soul of a woman named Maya, from where she was an impressionable girl fed with fables that instill all sorts of hope for her heart, to where is now as someone who has given up on romance and that promise of a truly happy ending.

Ulan is more about stories than it is about the idea of love. In the film, Maya is told stories. She writes private stories in her diary. She works writing stories for a publishing company. Her stories even come to life, with amorous tikbalangs and rage-filled typhoons interacting with her. Her very psyche is shaped by the stories she has been told and the stories she creates.

It just so happens that most stories that pervade our collective consciousness center on love.

The tikbalangs overcome forbidden love. The stories she writes for a living are the steamy romances which the public thirst for. The typhoon’s rage stems from unrequited passion. Her very psyche revolves around love, its pleasures and painful repercussions, only because everything she hears and absorbs pertains to affairs of the heart.

However, there is also more to the concept of stories than just love that Ulan touches on.

In its portrayal of Maya’s boss as a libidinous old man whose matter-of-factly remarks are overtly sexist, the film shines a light on how the stories made for public consumption are led and driven by men and their blatantly lascivious male gazes.

In a sense, Villamor’s film, which puts to the fore the power of stories, also comments on the very skewed psychology that has been allowed to thrive by the kinds of stories that have persisted and continue to persist.

There is just more to the film than fun and fantasies. It is deep and compelling.

Intriguing filmography

Ulan occupies a very important position within the intriguing filmography of Villamor.

From Relaks, It’s Just Pag-Ibig (2014), the road movie she co-wrote and co-directed with Antoinette Jadaone that navigates the blossoming romance between two youths, to Sid and Aya: Not a Love Story (2018), her very sober take on two possible lovers coming from diverse social and economic classes, Villamor has always made a defining stand not to belittle the romance either by abandoning it as a lower form of entertainment or leaving it to stagnate by pursuing only its escapist ends without even a whiff of discourse.

Villamor works hard to elevate the genre without trampling on its essential cliches and formulae.

Camp Sawi (2016) subverts the concept of women’s lives revolving around heartaches, turning making it the basis of an absurd setup of a man basing his business around it. Meet Me in St. Gallen (2018) shifts the structure of romances to tell the story of a man whose curiously fateful encounters with the same woman has him relying on the twists and turns of the romantic formula for his happy ending discounting the notion that the woman he believes is fated for him also has the ability to determine for herself. The same set-up and conclusion ring true in Sid and Aya: Not a Love Story.

In a way, Villamor’s films seek to overturn the simplistic mindset that has long governed the romantic genre and Ulan, which she wrote in 2005, grounds the theses to her creative revolution. Ulan’s voice and perspective are distinctly feminine. While it still utilizes tropes such as the homosexual confidante to the lead female, it is unbolted from very rigid plot structures of the genre. The film is often beautifully meandering. It doesn’t easily surrender to expected emotions, evoking joy and hope out of tragedy. It is utterly bewitching.

Novelty and substance

Also notable is how Villamor doesn’t simply lean on the novelty and substance of her material.

Ulan is a gorgeously crafted film. The performances of Nadine Lustre as Maya and Carlo Aquino as Peter, the man who makes Maya trust in both the stories and the capacity to love she has long hidden, are splendid. The ingenious production design and Neil Daza’s luscious lighting affords the film a look that complements its ambitions.

Ulan resists most of the conveniences of the genre, picks the contrivances that are necessary in its very many noble intents, and stands firmly as a solid piece of discursive entertainment despite its refreshingly odd mix of strangeness and familiarity.– Rappler.com

Francis Joseph Cruz litigates for a living and writes about cinema for fun. The first Filipino movie he saw in the theaters was Carlo J. Caparas’ Tirad Pass.

Since then, he’s been on a mission to find better memories with Philippine cinema.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.