SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

For decades, the world has grown accustomed to a simple and linear way of consuming products. You buy the product, use it until it’s worn out or out of trend, then dispose of it. There’s little awareness of what happens after disposal and where all the trash ends up.

The sad reality is that a lot of waste ends up in our oceans. According to a highly-cited 2015 study by the American Association for the Advancement of Science, around 4.8 to 12.7 million tonnes of plastics enter our oceans annually. The Philippines is among the countries contributing to 60% of the marine debris discarded in our oceans.

Scientific evidence and a growing restlessness over climate change and the environment have led to movements demanding a shift in the way we consume products, especially those with plastic packaging.

Pandemic-driven

Recent reports on plastic consumption paint an even more depressing picture, as the ongoing coronavirus pandemic has led the world to rely more on plastics. The use of single-use plastics surged following institutions’ efforts to curb infections.

In a study published last June in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, researchers calculated a monthly use of 129 billion face masks and 65 billion gloves globally during the pandemic. This amount of waste is not only an environmental problem but also a risk to public health.

On the other hand, the world’s medical frontliners need 89 million medical masks, 76 million gloves, and 1.6 million goggles monthly, according to the World Health Organization. While medical wastes are necessities amid the pandemic and are disposed of differently, most face masks used by the public are not disposed of properly and add to the world’s already accumulating waste.

Masks and gloves are disposed of after one use, and face shields are completely made from plastic. Public transportation and business establishments use plastic dividers to ensure safety and continue operations. And because people cannot go outside, basic necessities such as food, groceries, and household supplies are delivered to homes – most of them in plastic packaging.

According to Jacob Duer of the Alliance to End Plastic Waste, in Thailand, plastic waste has increased from 1,500 tons to 6,300 tons per day, caused by food deliveries at home.

The fight against the virus has compromised the battle against plastics. Many groups are concerned that the “COVID waste” will stall the hard-earned gains of the plastic movement worldwide.

It does not help that the Philippines is struggling to manage its growing waste and plastic crisis.

According to a 2016 report carried out by German consultancy firm GVM, at the municipal level, only 15% of waste is properly disposed of, while only 5% of waste is recycled. Most local government units (LGUs) have not yet institutionalized recycling practices at the ground level.

Initiatives

A lot of proposals have been made to tackle the country’s waste problem. Several senators, including Senators Risa Hontiveros and Nancy Binay, have filed bills seeking to ban plastic straws and bags in restaurants and stores.

Other lawmakers like Muntinlupa City Representative Rufino Biazon proposed a prohibition on the sale, use, manufacture, and importation of single-use plastics.

Quezon City, for example, was the first to open a condiment refilling station so people can get their supply using reusable bottles. (READ: Single-use plastics, still the environment’s number 1 enemy)

But to this day, the country’s waste management system continues to be inefficient, making these standalone efforts the exception rather than the norm.

The COVID-19 crisis also presents a unique challenge, one that will need a response that balances health and environment. The pandemic has highlighted the pressing need to make bolder action plans to combat plastic pollution.

A recent study commissioned by conservation organization World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Philippines proposed to the Philippine government and producers a waste reduction and management scheme that would oblige companies to take more responsibility for the products they put out on the market.

This scheme is presented as one of the initiatives to stop the flow of plastic into nature by 2030.

What is EPR?

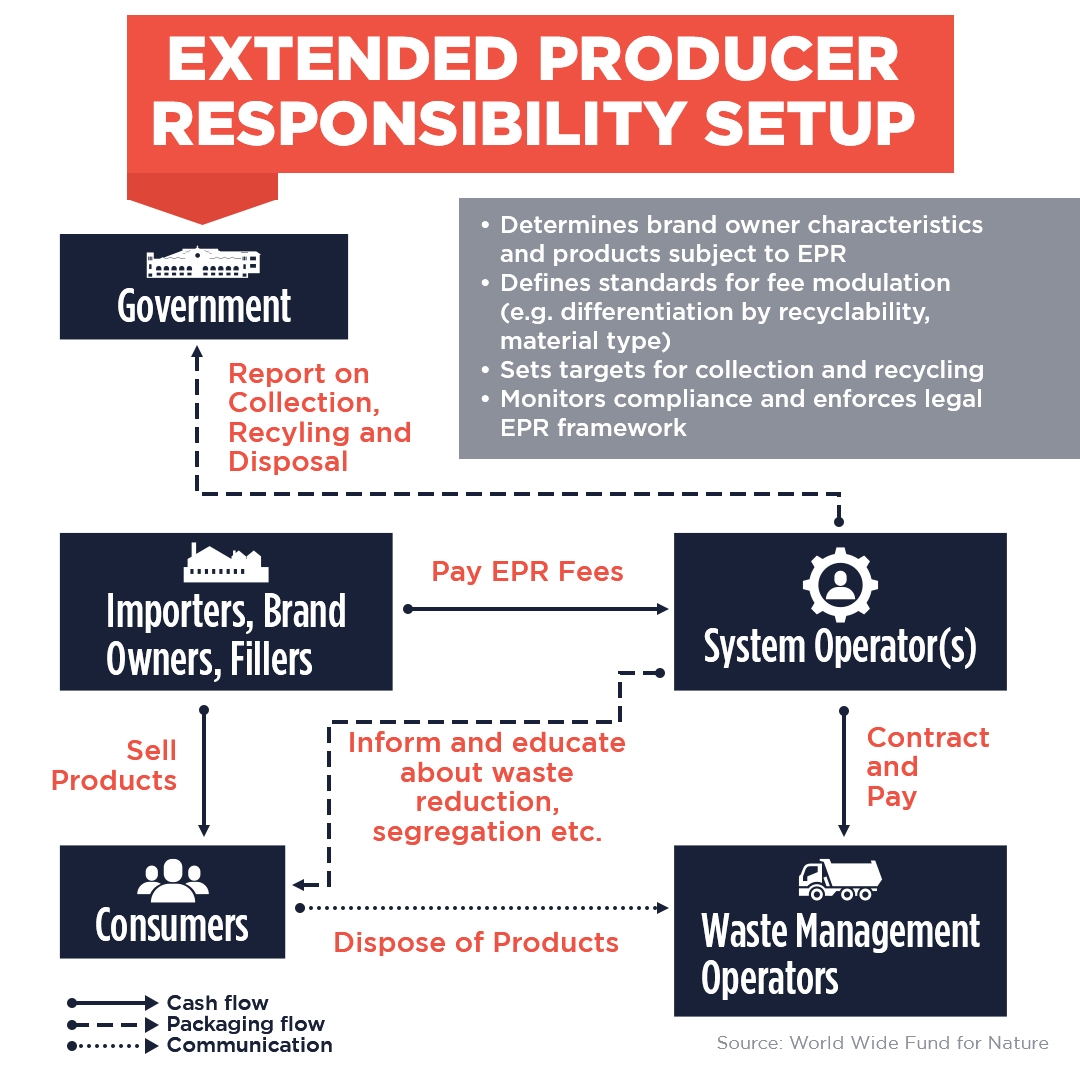

This waste reduction and management tool is the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), a scheme that reimagines the life cycle of products, ensuring that brands and manufacturers take responsibility for everything they manufacture and sell.

Instead of just churning out products that would soon become waste, companies are given the extended responsibility to dispose of and recycle their products post-consumption.

Under the EPR scheme, manufacturers should apply eco-design principles to their packaging to reduce the amount of material used and make a product easier to reuse and recycle. Companies are also required to coordinate with each other and with the government to properly dispose of their waste.

“Whoever brings the product out into the market, siya rin ‘yung may (is also the one with the) responsibility [of] how to deal with it after,” according to Grip Bueta, an environmental lawyer who has been working on EPR and plastic pollution in the Philippines for around a decade.

Bueta works as a consultant for various non-governmental organizations like EcoWaste Coalition, and for judicial capacity building on environment and climate law at the Asian Development Bank.

The EPR scheme will obligate those who place packaged goods on the market to pay for the cost of collection, sorting, recycling, and safe disposal. With the scheme in place, companies will be prompted to reduce plastic packaging and be more proactive in lessening the amount of plastic they produce.

“[Companies] will either directly collect and treat their post-consumer packaging waste, or pay a waste management operator to do so,” the WWF Philippines said in the report they completed last August.

The mechanisms on how companies will execute this responsibility will vary from one country to another, given the current state of each country’s waste management system.

How will EPR work?

Every citizen has the right to a healthy environment, supported by an effective solid waste management system.

In the Philippines, this right is enshrined in the Philippine Constitution, recognized in Republic Act No. 9003 or the Ecological Solid Waste Management Act of 2000. According to Bueta, the law itself is already comprehensive, even describing it as a “world-class law.”

The problem, he said, lies in the implementation.

“It all boils down to the government’s implementation, and to provide resources,” Bueta said, noting that the implementation of RA 9003 will affect EPR. He was referring to the effectiveness of legal safeguards that multinational companies have to follow and the working dynamics of the private sector and government.

By law, LGUs are primarily responsible for drafting policies, collecting, recycling, and composting of waste, as well as maintaining materials recovery facilities and sanitary landfills.

But according to the WWF Philippines, there are only 10,730 materials recovery facilities in the country as of 2018. They cater to a meager 33.3%, or 14,000 out of the total 42,046 barangays in the Philippines.

Waste collection is remarkably inefficient in heavily populated and inaccessible areas. After studying the rate of disposal in each region vis-à-vis wealth, the WWF Philippines concluded that waste disposal is directly related to the level of income in the area.

Low-income LGUs have a hard time implementing the provisions in RA 9003 due to “limited funds, space availability, and resources,” as seen in recovery facilities that are only used as storage for segregation.

Plastic regulation is also inconsistent among LGUs. In the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, for example, there are no LGUs enforcing plastic policies. (READ: Sachet away: What’s lacking in our plastic laws?)

One of the goals of EPR is to “stimulate” a holistic waste management system, reorganizing the system already in place, and filling the gaps of inconsistencies in plastic regulation.

EPR closes the plastic flow loop, making sure that waste is processed and reproduced as other packaging items, and does not end up in the environment. Ultimately, it facilitates a reduced amount of plastic from producers.

An EPR system is only possible “if we have a clear plan and all stakeholders commit to implementing EPR and looking at different issues,” Bueta said. Given the situation, establishing another system such as the EPR may overwhelm the status quo.

With LGUs already lacking funds to properly implement the current solid waste management system, who is going to finance the EPR system?

Under the proposed scheme, companies will also have to pay a fee for every plastic packaging they put out. The fee for recyclable packaging is less compared to non-recyclable packaging. The higher the volume of packaging the companies put out, the higher the fee they will have to pay.

These fees will fund this waste management scheme. It will also divert government funds from waste management and realign them to other equally important social services such as education and health.

According to Ocean Conservancy’s Plastics Policy Playbook, EPR fees can close the financing gap by about 75%. This will ensure consistent and quality waste collection and recycling.

Producers are encouraged to make their packaging recyclable. They may even change business models to adapt to their new mandate, opting for refillables and reusables. The fees will go to a fund that will finance the process of waste collection, treatment, recycling, and disposal.

All stakeholders, especially the private sector, will be organized in a Producer Responsibility Organization (PRO), a system operator that will ensure that responsibility is fair and distributed properly within the industry.

In Japan, for example, their PRO called the Japan Containers and Packaging Recycling Association (JCPRA) actively coordinates with concerned government ministries, municipalities, and consumers.

JCPRA started recycling glass and PET bottles in 1997, and successfully expanded operations to include paper, plastic containers, and wrappers in specified business entities by 2000.

The JCPRA is closely working with 5 government ministries on environment, trade, finance, welfare, and agriculture. As of 2018, the JCPRA processed 82,492 contracts with businesses, amounting to 1,563,937 tons of containers and wrapping recycled.

Where do we go from here?

Filipino culture and consumer habits play a role in why the country produces so much waste, particularly plastic. Much has been said about the tingi (retail) culture, where Filipinos buy products in single-use packages – a practice exacerbated by poor living conditions and limited household budget.

Communities from the lower-income brackets do not have much choice in the way they consume. Shampoo, soap, and food sachets remain the most affordable and easily accessible items. When living becomes a matter of surviving the day-to-day, it is harder to police the way people buy basic necessities.

One of the first steps in changing this and other similar practices is to pass legislation that will jumpstart a national effort toward a more effective waste management system in the country.

Bills seeking to legislate EPR are currently pending in the Senate and Congress. Senator Cynthia Villar authored Senate Bill No. 1331, which amends RA 9003 to include EPR.

Cagayan de Oro 2nd District Representative Rufus Rodriguez also filed House Bill No. 6279, which mandates companies to achieve plastic neutrality in 10 years. Both bills are still pending at the committee level as of October 2020.

For Rodriguez, a total ban on plastics in the Philippines is not possible “as it will have a negative impact on ordinary Filipinos,” he told Rappler.

“If we ban plastics, prices of consumer goods will increase, as alternatives to plastics are more expensive,” Rodriguez added.

The congressman finds EPR as as alternative to a total plastic ban. In his bill, the main objective is to oblige producers to collect the same amount of plastic packaging as they had initially put out.

A total ban will “have a negative impact on ordinary Filipinos,” according to Rodriguez. His bill seeks to make companies accountable, pushed by what Rodriguez calls the “producer pays” principle.

For Bueta, EPR is just one of the many waste management tools we can use to fix the country’s plastic problem. He emphasized a whole of society approach – from the government’s political will to implement policies, the private sector’s willingness to cooperate, to the public’s active participation.

As the Philippines juggles its pandemic response with the surge of single-use plastics, Congress approved House Bill No. 6864 which, among many important provisions, emphasizes the strict monitoring of waste management during the pandemic.

Dubbed the “Better Normal” bill, it provides incentives to manufacturers who will shift to more eco-friendly packaging alternatives. The bill is currently pending at the committee level in the Senate.

Addressing plastic pollution requires measures from all phases of consumption.

According to the WWF Philippines, “it is important to focus on both reduction of the production and the consumption of unnecessary plastic.” These efforts should ensure that “materials are used as long as possible in our society.”

Bueta, too, said the country must go beyond waste management.

“There should be a focus on reducing waste in the first place. Promote green and eco-friendly alternatives. Even approaching the zero waste,” he emphasized. (READ: How going zero waste is addressing PH’s plastic pollution)

But for now, any development that challenges the current line of production and the country’s culture of consumption is welcome.

In its report, the WWF Philippines said EPR as a sustainable waste management tool “is an inevitable element for achieving a well-functioning circular economy.”

For advocates, EPR may pave the way for a more sustainable economy that breaks away from the current linear economy where we just buy, consume, and dump. – Rappler.com

This story is produced in partnership with the WWF Philippines.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.