SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines — Bea Rose Santiago’s crowning as Miss International 2013 — the fifth time a Filipina has won this prestigious title in the beauty-pageant circuit — is a good occasion as well to remember when it first happened: when Gemma Guerrero Cruz secured for the Philippines its place in this milieu, winning as Miss International in 1964 and becoming the first Filipina to claim the global stage of a leading beauty contest.

In hindsight, Gemma’s victory has become widely appreciated as a lapidary moment in postwar Philippines, particularly reflective of the energetic Sixties. In time, perhaps, the year of Megan and Bea Rose (as well as Ariella Arida) will also be remembered in the context of its own critical period — theirs being a collective triumph for their countrymen amid scandal and adversity.

Mixed feelings

But if 1964, or what one magazine had already called at the time “The Year of Gemma,” is a special chapter in the nation’s memory, that episode had also elicited very mixed feelings in her family.

The Guerreros had long distinguished themselves in the sciences and letters, alongside their passionate chronicling of the country’s history and heritage. And then, this Guerrero daughter, who is also a descendant of Rizal’s family (from the line of her father, the late Ismael Cruz), decides to join a beauty contest!

In this interview with Rappler, Gemma Cruz-Araneta regards fondly, and with much humor, that episode when she was barely out of her teens. It began almost as a fluke inspired by two friends.

“They submitted my name,” she said. “Siguro katuwaan, ewan ko lang ha? They kept convincing me and I said, ‘Hay naku, hindi ako puwede diyan.'”

But Gemma relented anyway, thus walking into a winding corridor, crowded by the usual glamor circus, that led to the stage of her coronation as Miss Philippines in 1963.

That contest was a franchise of the City of Manila that also served as a fundraiser for Boys’ Town and Girls’ Home, Gemma said. But this social component did not convince her family, although she was now obliged to take part in Miss International as the official Miss Philippines.

The resistance came naturally from her mother, the journalist and historian Carmen Guerrero-Nakpil, but more so from her uncle: the diplomat, journalist, and historian Leon Ma. Guerrero.

“I didn’t ask permission from anybody,” Gemma said. “I wouldn’t be granted permission anyway. They were so aghast, and my uncle, who was the ambassador then to England, sent a telegram to my mother: ‘¡Basta de barbaridades!’ [Enough barbarity!] They didn’t know I was going to do it, and when they found out, it was just too late to [stop me],” she laughed. “And they probably thought, well, why not?”

‘Frivolous side’

In “Legends and Adventures,” the second of her 3-book memoirs, Carmen Guerrero-Nakpil recalls that Gemma “had [just] been granted a scholarship in museology by one of the greatest museums in the world, the Museo Antropologico in Mexico City.”

Here, this article liberally quotes from that book:

“But like me, she had a paradoxical, frivolous side,” wrote Mrs. Nakpil, “and she also wanted to give the Miss International title a shot. I was against it because I considered beauty contests idiotic, demeaning spectacles. But remembering my misery from the repression I suffered in my early years in Ermita, I always tried to be as liberal as possible with my own daughters. I gave my consent provided I could be her chaperone. I figured that she would not win the contest anyway, and that, from Long Beach, California, where the beauty pageant would be held, we would afterwards travel to Mexico together in time for her scholarship.

“What followed was an exhilarating whirlwind of activities, new to me, but apparently common to beauty pageants. Rehearsals, fittings, photo shoots, parties in and out of town, visits to film stars’ homes and Hollywood studios, the works.”

The Filipino community in California was suddenly missing, said Mrs. Nakpil. “A Filipino beauty salon said they were fully booked for the week. A Filipino photographer charged an exorbitant amount for photos.”

“Of course, nobody expected me to win,” Gemma told Rappler. “Nobody in the Philippines expected me to win. I did not conform to the Filipino’s idea of beauty.”

Ambassador Guerrero himself, in his interview with fellow Free Press veteran Nick Joaquin, months after Gemma’s victory, said he doubted that she would even make the semi-finals. Then he heard the news and reported to his wife with some perplexity and relief, “Well, she made it.”

Gemma said it was the Q&A, as widely expected, that proved to be the crucial portion. The question, as she recalls it, went something like, “Do you want to win this contest and if you do, what are you going to do with the prize money?” Which at the time was a hefty US$10,000.

“So I said yes, I want to win this contest,” she said, laughing. “But not for myself, but for my country. And I’m going to donate the money to Boys’ Town. I will build a house for them, for the children who sleep in the streets of Manila.

“My mother said afterwards, ‘Uh-huh, you know your politics. Because the Americans always want to know what you’re going to do with the aid they give you.’ Of course, she was joking.”

It happened that this event became, toward its end, a contest between Miss Philippines and Miss USA. The representatives of Brazil, the United Kingdom, and Finland were already named the second, 3rd, and 4th runners-up.

When Miss USA was named 1st runner-up, “I was really so happy — and relieved!” Gemma said. “Because this was the first time the Philippines won an international title.”

Character, myth

To her mother’s amazement, a party at the Philippine consulate was held soon after Gemma’s victory, “and 5,000 ecstatic Filipinos came. Under my breath, I asked, ‘Where were you when we needed you most?’ The axiom about Filipinos loving the underdog is a myth. Filipinos adore winners, but only after they’ve won. We were deluged with attention, gifts, parties, declarations of undying affection. Gemma had to give up her scholarship and her career as a museologist. I learned my lesson in Filipino character and the effects of long colonization.”

The victory became sweet to both mother and daughter because, wrote Mrs. Nakpil in her memoirs, “We had both suffered from the taunts of the mestizeria in Ermita and now tended towards triumphalist glee. Viva la gente morena!”

Mrs. Nakpil was also proud of the fact that “a whole new generation” of Filipino women thereafter was named “Gemma” (so affirmed by Rappler’s Gemma Bagayaua-Mendoza). “But if you ask me, I’d rather not be a beauty queen’s mother ever again.” The term for this role in our frenzied time is “momager.”

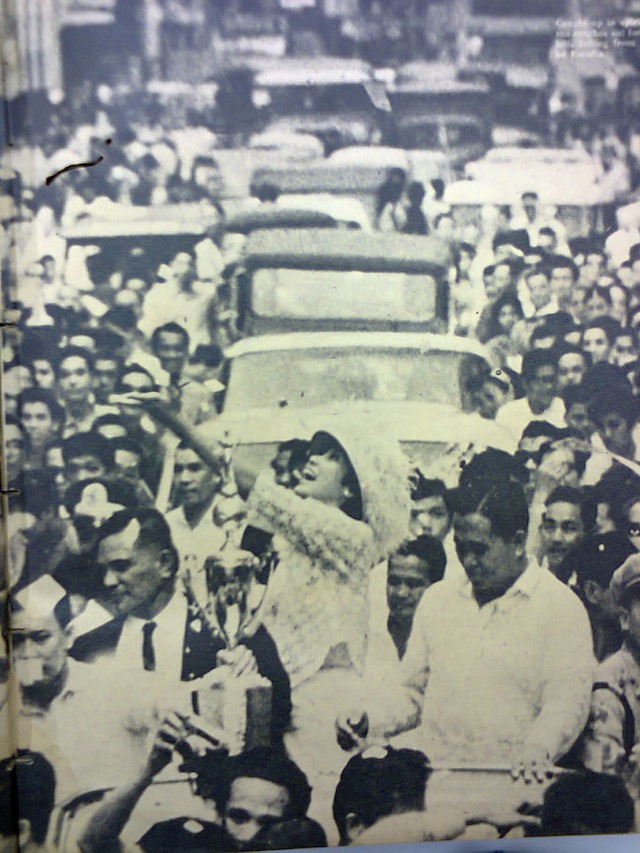

Gemma was given what her mother described as a “vertiginous welcome,” akin today to the customary pandemonium greeting Manny Pacquiao and Megan Young. Gemma’s homecoming was a zeitgeist moment in Downtown Manila during that now-bygone August.

“I arrived in Manila at 7 am,” she said. “Hay naku, who’s going to wake up by this time? The Bayanihan troupe happened to be with us. And I looked out the window and I was very surprised. Huh? Ang daming tao! Nandoon pa yung band ng Boys’ Town.

“A classmate of mine said she was trying to get on her flight while I was coming in. She almost missed her flight and said she will never forget it because, in the midst of all that commotion, I saw her and I waved at her.”

Miss International was treated to a ticker-tape parade from the airport to the Escolta, then to Sta. Mesa all the way to her home in San Juan.

Aguinaldo, Beatlemania

In retrospect, the Year of Gemma was a transition year. President Diosdado Macapagal had reverted the celebration of Independence Day to its original date – from July 4 to June 12 – and Gemma remembers taking part in that parade, a year before flying to Long Beach.

“I was on a float of the Department of Education because I was working for the National Museum then. I was already Miss Philippines and I saw General Aguinaldo seated among the guests.”

That was Emilio Aguinaldo’s last public appearance. On a balmy February the next year, the General, who had been confined at Veterans Memorial Hospital, succumbed to cardiac arrest after a series of cerebral strokes. He was 94. The “passing of en era” is a commonly attributed cliché to anyone’s death but never more true as it concerned the General.

By this time, Beatlemania had invaded this country and the world. Manila would launch its first film festival two years later. The Philippines had affirmed its past but was also looking ahead. Poverty, a predominant setting in Joaquin’s classic reportage on crime, had always been a striking feature of the country and its center, Manila (Quezon City was the official capital then), as Gemma herself referred to in her Q&A in Long Beach. But the Manila of that era was still a different world.

Ambassador Guerrero, who returned home soon after Gemma’s victory, remarked to Joaquin how Manila had become “much more beautiful than when I saw it the last time.” But he was flabbergasted by the predictable reception accorded to visiting Spanish aristocrats during his homecoming. “I would have wanted them to go walking on Azcarraga,” he said of the historic Downtown avenue that had been renamed after his departed associate in the profession of law, Claro M. Recto. “How can you find Filipinos in Forbes Park, for goodness sake! It’s really stupid.”

Quiet disciplines

Meanwhile, Gemma’s life went back to normal, for a while. She married Philippine Graphic editor Antonio Araneta a year later, raised their children, and pursued the quiet intellectual disciplines of her family. She was obliged to pass up the usual opportunities awaiting a beauty titlist, including “an offer to appear in a movie with FPJ,” but she accommodated an endorsement for a sandwich-spread product that was in line with its sponsorship of Boys’ Town.

Mostly, Gemma turned to what the Guerreros did best — research and writing. She won prizes for her fiction, at one point sharing the top prizes of a magazine contest with Eman Lacaba and Lina Espina-Moore. And, among other things, she wrote a children’s book and a beauty book, as well as her much sought-after “Hanoi Diary” — her account on the Vietnam War (happily in print again), together with Antonio Araneta. Then came what Nick Joaquin described as the “masterly sophistication” of “Sentimiento,” Gemma’s collection of fiction and articles on heritage, published in the Nineties.

Mostly, Gemma turned to what the Guerreros did best — research and writing. She won prizes for her fiction, at one point sharing the top prizes of a magazine contest with Eman Lacaba and Lina Espina-Moore. And, among other things, she wrote a children’s book and a beauty book, as well as her much sought-after “Hanoi Diary” — her account on the Vietnam War (happily in print again), together with Antonio Araneta. Then came what Nick Joaquin described as the “masterly sophistication” of “Sentimiento,” Gemma’s collection of fiction and articles on heritage, published in the Nineties.

The title story itself is a globetrotting escapade set in the mundane world of NGO work, featuring a Filipina stationed in Central America and the two men in her life who turn out to be “prosaic” beneath their glamor, as Joaquin commented in his blurb for this book. One of the men, he wrote, is “a Latin lover, lousy in bed, who has to be ‘overpowered.'” The real glamor is in Gemma’s writing:

“He asked the usual leading questions of any Chief of Mission arriving at a new post, wondering if his assistant could be turned into a trusted ally. Then with a quick change of mood he asked, frowning slightly, why a Filipina should circumnavigate the world to Nicaragua, to work on development projects, while her own country was the despair of funding agencies because it had a low absorption rate of 30 percent. He declared in a rather pontifical tone that I should have stayed in the Philippines and done something about it, instead of contributing to my country’s ‘brain drain.’ I was flustered by his expected disapproval, to say the least, but before resentment could set in, he very cleverly gave the conversation another turn and happily observed that the agency was not in the shambles he had dreaded to find and thanked me for ‘manning the fort’ until the Chief of Mission arrived. He stood up and with a courtly bow left my office. I could not figure out what had hit me.”

Soon enough the characters become intimate. “I anticipated his wishes; never betrayed his insecurities and trusted him with my own. Yet, he was somehow perturbed by the very candor that he found refreshing. Whenever he asked why I loved him I replied, very simply, that he was the man I had always wanted to meet. ‘Words of a sphinx,’ he would say, ‘with no logic nor reason.’ To which I answered, ‘Love is the absence of thought.'”

Gemma acknowledges that she doesn’t write as much fiction as she used to. “You sort of get caught in the day-to-day activities,” she said. But she still writes “because, once you stop, para bang you’ve stopped playing the piano.”

This writer complimented Gemma for being kahawig with the current Miss International. She said “Thank you,” and as we were back on that subject, she pointed out the “great responsibility” that a title holder must wield even after her reign.

“I’m really grateful to my countrymen because at this late day, they still remember and are appreciative. But people will always be attentive to what you say.” She smiled. “Dapat talaga wala nang barbaridades.” — Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.