SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

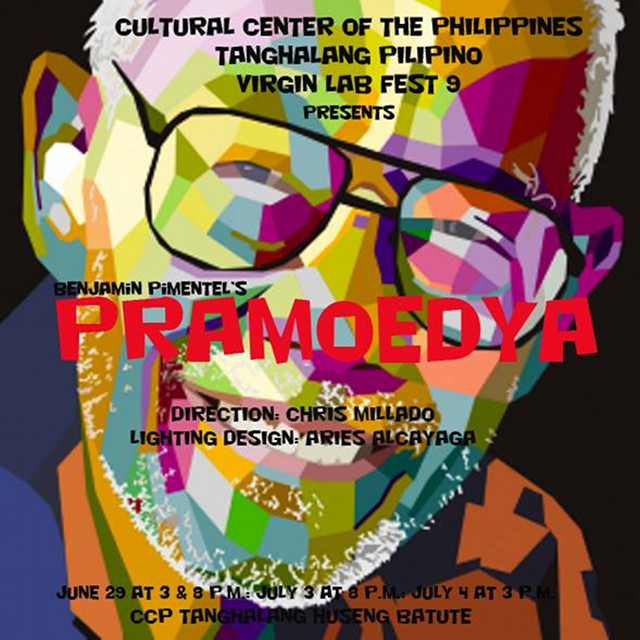

MANILA, Philippines – On Thursday, July 4, I decided to give my daughter and myself a rare treat. We headed to the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) to catch the last playdate of Benjamin Pimentel’s “Pramoedya.”

READ: The passion of Pramoedya

In graduate school, I was introduced to the work of Pramoedya Ananta Toer, an Indonesian writer and Ramon Magsaysay awardee for literature. A nationalist, Pramoedya rebuked his writer colleagues for supposedly allowing themselves to be manipulated by the military in post-colonial Indonesia.

He paid dearly for his views when the dictator Suharto cracked down on communists and nationalists, killing an estimated two million people. Pramoedya was arrested; and without formal charges or a trial, was detained indefinitely in an island prison.

Besides my interest in Pramoedya’s biography, I was looking forward to watching a play written, directed and acted in by friends. The play’s director Chris Millado, playwright Boying Pimentel, lead actor Fernando “Nanding” Josef and I were contemporaries in the protest theater of the streets during the last years of Marcos’ martial law.

Lacking theatrical skills, I was happy to take on the generic chorus roles of the taong bayan or assist with mundane tasks behind the scenes. But with or without talent, I was ever present, performing street plays during rallies, thinking this was my sole act of protest against the dictator Marcos.

Boying asked permission to have us seated in the front row. I grinned my relief; the front row had cushioned chairs which were definitely more comfortable than the hard bleachers of Tanghalang Huseng Batute. Early on, it was obvious that the play “Pramoedya” was well-crafted, well-acted and well-staged.

The audience meets Pramoedya on the eve of his arrest. A friend comes to warn him of imminent danger but the novelist maintains that he has nowhere to go, and thus opts to stay home. Suharto’s soldiers come and arrest him, and he begins a desolate life as a political prisoner on an island he shares with criminals.

Bereft of pen and paper, Pramoedya “writes” his best work, holding nightly storytelling sessions, admonishing his co-prisoners to remember and repeat his tales. The story of Minke (Indonesian for “monkey”), a bright, young university student who wins the love of a half-breed, Dutch-Indonesian beauty, takes hold of the inmates’ imagination, making life on the stark island a bit more bearable.

Cris Villonco plays Fides, a young Filipina journalist on a quest to find and interview the renowned Pramoedya. Fides’ passion in meeting Pramoedya is fueled by her own past. As a college student activist, she berates her younger brother Bobby for his seeming lack of social conscience.

She belittles Bobby’s passion for Led Zeppelin’s rock music and drags him to participate in various protest actions against the Marcos dictatorship. Eventually, Bobby surpasses her commitment, choosing to join the underground revolutionary movement and its militia, the New People’s Army.

The opportunity for Fides to meet Pramoedya comes when the latter is bestowed the Ramon Magsaysay Award. After 15 years on the island prison, Pramoedya is now under house arrest, and Fides arranges a sought-after interview. It is during Fides’ visit that Pramoedya’s writer-colleagues hold a press conference bringing to the fore questions on the writer’s integrity.

They claim that Pramoedya, then favored under the previous Sukarno government, withheld his assistance when his colleagues were imprisoned for espousing their own anti-government views.

The play’s multi-faceted conflicts are brought to a head. Pramoedya grapples with his personal definitions of nationalism and democracy; Fides, with the guilt inadvertently caused by her brother’s death after her prodding him to join the revolution; and Minke, of Pramoedya’s tale, with his futile struggle to free his wife from her distant but maneuvering colonial family.

Increasingly, I felt uncomfortable in my comfortable seat. On stage, Fides has taken on her dead brother Bobby’s persona. “Ok lang ako, Ate…” (I’m okay) he says as he is personified through Fides. In a monologue, he admits that the life of a guerrilla is difficult but nonetheless continues to extol the revolution, the only palpable challenge to the dictatorship.

The monologue struck close to home. How often would I read these same words in letters from my brother Ishmael Quimpo, or Jun, as we called him. A University of the Philippines college freshman, he had also metamorphosed into an NPA guerrilla.

In his letters, Jun narrated how fungus had encrusted his feet and those of his kasama (comrade); how pus would flow from their open wounds and cracked skin. And because antibiotics were unavailable, Jun had offered his own antidote — he serenaded his squad with a song he composed, entitled, “Pasiglahin Mo ang Iyong Pag–asa” (Renew Your Hope).

Like Bobby, Jun downplayed the perils and pains of guerrilla life, choosing to focus instead on the certainty of freedom from oppression and of the revolution’s victory.

The lights on stage dimmed and strobe lights cast shadows on the figures on stage. Pramoedya, resolute that his actions were meant to protect “ang aking Indonesia,” (my Indonesia) is in a near-fetal position, weeping, resigned to the fact that the long years of imprisonment were not enough to prove his loyalty and love for country.

Pramoedya’s co-prisoner is also on stage, half-naked, struggling with a bamboo cage encasing his head. Fides, still playing Bobby’s persona, is in mid-stage, arms, hands and legs outstretched as if bound and held in mid-air by heavy ropes. The Bobby persona has stopped praising the revolution; instead, in a cracked voice, he renders a few lines of Led Zep’s “Stairway to Heaven”:

And it’s whispered that soon, if we all call the tune,

Then the piper will lead us to reason.

And a new day will dawn for those who stand long,

And the forests will echo with laughter.

Bobby twists and strains as he sings the song. He is being tortured by his own comrades, the very people who shared his dream of freedom for the Motherland. As with Pramoedya, Bobby’s years of service to the revolution were not enough to prove he was no spy. Gone were the accolades for the revolution. Bobby ends with a piercing cry: “Ate, tulungan mo ako!” (Help me!)

My brother Jun’s song was silenced, too. Like Bobby, Jun was silenced by 7 bullets from a comrade’s gun.

The stage lights come back on, followed by the announcement of intermission. I glanced at my 17-year-old daughter seated next to me. Next to her sat Joy Jopson-Kintanar and her 31-year-old daughter. I hold deep respect for Joy; twice widowed, she is one of the heroes of the revolution. Her first husband, Edgar Jopson, was a student-leader-turned-revolutionary. He was gunned down by Marcos’ military in their attempt to capture him.

Her second husband was Romulo Kintanar, one-time head of the New People’s Army. He too was gunned down by unknown assassins, ironically when he had decided to lead the life of a civilian to care for his family in post-Edsa 1986, the end of the Marcos dictatorship.

I saw Joy quietly brush away tears into a handkerchief. I felt relieved — at least one other person in the theater understood and shared my bottled-up sentiments. I whispered to my daughter, “Naintindihan mo ba yung last scene?” (Did you understand the last scene?)

“Hindi masyado,” (Not much) she answered. I fumbled for words. How does one explain the revolution? How can one give credence to the fact that during the mid-1980s, the revolution was infiltrated by military spies and in a wave of paranoia, kasama turned against kasama, ordering each other’s torture and death in a frantic bid to purge?

The kasama who survived that “purge” estimate that some 600 to 3,000 were killed by their own. I struggled to explain the revolution and the purge during the intermission. In the end, I felt frustrated, failing miserably to do justice to those killed, knowing there was little recourse but to over-simplify history.

I wished I had the done the more natural thing, cry into my handkerchief like Joy did. I wondered if her young daughter and mine could truly ever imagine the horrors behind the tale of revolution now theatrically depicted before us.

In Pramoedya’s story, Minke’s half-breed wife is forced to leave him and live in the cold Netherlands, with her Dutch relatives. There, away from anything and anyone who could give her warmth, she dies.

The protests against him do not prevent Pramoedya from receiving the Ramon Magsaysay Award but he is barred by his government from flying to Manila to personally accept it. Fides thanks Pramoedya and says her goodbyes.

But like Pramoedya, she wonders why victory and freedom feel like defeat.

At the end of the performance, I stood up, quite unnerved. I came to watch a play about an Indonesian author; I certainly got more than what I came for.

Instead, I was reminded of the little-known historical facts I had lived through, of a revolution gone awry, of a purge that killed its own, and of the tortured and dead still needing to be acknowledged.

And to us who joined this revolution and who survived the horrors of martial law, why then does victory and freedom still feel like defeat?

I found it hard to sleep that night. I wondered if Joy got any sleep, either. – Rappler.com

Susan F. Quimpo is the co-editor/author of “Subversive Lives : A family memoir of the Marcos years” (Anvil Press, 2012). The book is about the story of the Quimpos, a family of activists, and their experiences under martial law.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.