SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Invasions aren’t always spearheaded by armies. Sometimes a released pet is all it takes to transform a country. What are the most commonly encountered Philippine animals?

Invasions aren’t always spearheaded by armies. Sometimes a released pet is all it takes to transform a country. What are the most commonly encountered Philippine animals?

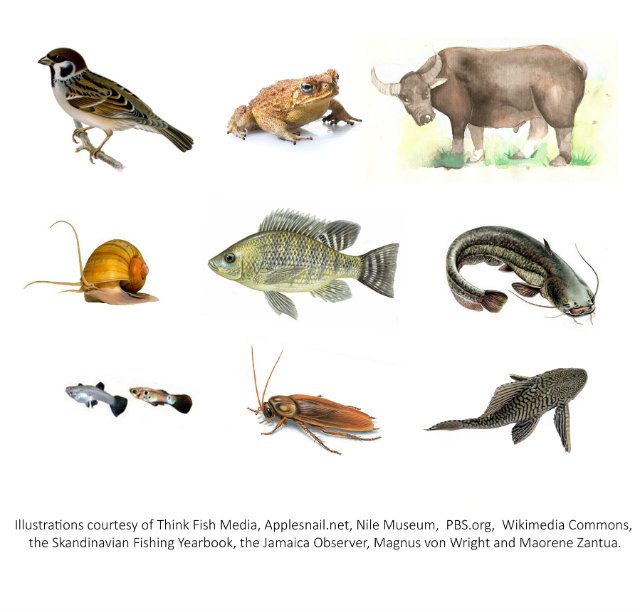

If the maya, tilapia, ipis, dagang estero, or kalabaw are top-of-mind, you’re in for a surprise. Despite being ever-present, none of them originated from the Philippines. (READ: Elephants, rhinos, tigers in the PH)

Introduced by accident or on purpose, exotic species can overpower native plants and animals in just a few generations. How prevalent are introduced species in the Philippines?

Maya birds fom Europe

Maya birds were actually imported from Europe to combat loneliness. And they’re impostors too. The term maya once referred to a group of small, gregarious birds – particularly the richly-hued chestnut munia (Lonchura atricapilla) which was our national bird until 1995.

Legend has it that lonely Spaniards, wishing the Philippines to feel more like their beloved Spain, brought Eurasian tree sparrows (Passer montanus) with them in the early 1900s.

A century later, they’ve become our most familiar bird, flitting over every major Filipino island, town, and city sometimes plaguing ricefields. Sadly, most Pinoys now mistakenly believe the introduced Eurasian tree sparrow is the real maya when in fact the original one is the chestnut munia.

Imported African tilapia

Originally hailing from Africa and the Middle East, tilapia has become among the world’s most important food fish. It is grown in 70 countries. Mozambique tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) were brought to the country in the 1950s, followed by Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in the 1960s. The territorial and prolific mouth-brooders took over all major Philippine waterways within 50 years.

Tilapia can decimate the native fauna of many rivers and lakes in the Philippines and elsewhere. In Lake Victoria, Africa’s largest, the introduction of Nile perch and tilapia has spurred the extinction of 60% of the lake’s native fish in what may be the biggest vertebrate extinction of the 20th century.

Dagang estero as expert ship stowaways

Hailing from northern China, dagang estero or brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) invaded every continent, save for Antarctica by hitching aboard ships. They are the most widespread mammal next to humans.

Typically seen slinking around grimy alleys and gunky canals at night, these all-gnawing rodents have annihilated many island species, especially birds. In Palawan’s Bancauan Isle, introduced rats wiped out all ground-breeding seabirds. Rats are also smarter than we think, they’re as intelligent as dogs – learning fast and remembering solutions to complex problems.

Colorful guppies and malaria

Introduced in 1921 to keep mosquitoes at bay, prolific “millions fish” or guppies (Poecilia reticulata) have spread to just about every waterway in the country. They dine on wriggling kiti-kiti or mosquito larvae. However, not all introduced species are harmful. These lively livebearers – they pop out little guppies instead of laying eggs – control mosquito-borne diseases like dengue and malaria. Hence, they help make our country a safer place.

Giant cane toads, pests, and sugarcane fields

Their success story is truly riveting. Giant cane toads (Rhinella marina) eat more than insects. They gorge on anything – small birds, mammals, reptiles – even other toads! With their toxic, leathery hides and rabbit-like reproduction rates, they’ve become the Philippines’ most common amphibian – sitting at the top of the heap in their warty, bug-eyed glory.

Alien catfish displacing the native hito

Introduced for food, African sharptooth catfish (Clarias gariepinus) and Asian walking catfish (Clarias batrachus) are displacing our delicious local hito or the broadhead catfish (Clarias macrocephalus), which is now dwindling because of land conversion and hybridization with the two alien species. A good reason to conserve our broadheads? Among the 3 species, ours is still the tastiest.

Golden kuhol from South America

“What better way to feed people than to throw South American snails into ricefields?” thought entrepreneurs in 1982. Well, these little golden buggers don’t spread at a snail’s pace. Eight years after introduction, golden apple snails (Pomacea canaliculata) and their familiar pink egg clutches infested 11% of the Philippines’ ricefields, turning our palayan into their personal salad-bowls. Tasty yes, but these gastronomic gastropods are now top rice pests.

American cockroaches and commerce

By stowing away on ships, planes, trucks, bags, and anything small enough to crawl in, American cockroaches (Periplaneta americana) colonized the world, contaminating food stores with cockroach crap.

Aside from being unbelievably tough to kill – they can take a full-force slipper-slap and still merrily scurry into a wall-crack – they’re armed with a truly terrifying move: the flying ipis (cockroach) attack.

Carabaos brought in by Malay settlers

Originating from India, Indochina and China, wild water buffalos were domesticated approximately 5,000 years ago. Malay settlers brought carabaos (Bubalus bubalis carabanensis) to till the isles which would someday be the Philippines around 2,200 years ago. The beloved, hardworking carabao has now been naturalized as our national animal.

Dumped South American janitor fish

No invasive species story would be complete without mentioning janitor fish, particularly the common plecostomus (Pterygoplichthys pardalis) and sailfin plecostomus (Pterygoplichthys disjunctivus). Aquarists just love these tireless sucker-mouthed algae eaters, which hail from the fast-flowing waters of South America.

Unfortunately, they grow larger than a foot, way too large for most aquaria. Well-meaning pet-keepers then dumped them in rivers. Voila, the infestation has spread as far as Mindanao. Looks like we’re the real suckers.

Introduced, invasive or naturalized?

Chinese soft-shelled turtles, South American knifefish, Central American jaguar guapote , the list goes on and doesn’t even include plants.

So what differentiates introduced and invasive species? Introduced species have little large-scale effects on the environment, while the invasive outwits, outplays, and outlasts most other species.

Many animals have also become naturalized as stable components of ecosystems. The famed mustang horses of North America were brought by Spanish conquistadores to the New World 522 years ago.

The legions of ancient Rome introduced pheasants from Asia to Europe 2,100 years back. Australia’s ubiquitous rabbits are descended from 24 European bunnies that a farmer set free 156 years ago. Well yes, they breed like rabbits.

Over time, these animals blended into their new habitats.

To stem the tide of alien invasion, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) developed a National Invasive Species Strategy and Action Plan. “We can no longer ignore this issue for its impacts have extended beyond what we consider intangible. We’re losing our potential to further benefit from our native biological resources,” explained Dr Theresa Mundita Lim, head of the DENR’s Biodiversity Management Bureau (BMB).

Your role in all this

Hobbyists and farmers could stop releasing non-native animals into the wild.

You can also take photos of unfamiliar animals and send them to the DENR-BMB or post them online to map out the range of both foreign and local species. “It’s important to recognize the various pathways for entry like tourism, agriculture, forestry and the pet trade,” said Lim. “We want to best manage the entry of invasives by working closely with those responsible for each pathway.”

Knowledge is power.

Careful culling can also dent introduced populations. Using aids like poisoned bait and advanced tracking, New Zealand successfully removed invasive rats in 10% of its islands, proving that eradication is possible in closed island ecosystems.

But controlling invasive fish and farmed species is more complicated. “Invasive predators like knifefish are among the worst, having eroded the fisheries productivity of Laguna Lake,” stressed Dr Ma. Rowena Eguia, head of the Manila office of SEAFDEC, an international body which promotes sustainable fisheries development in Southeast Asia.

“However, many invasive species like tilapia have also become important aquaculture mainstays, providing millions of people with food and livelihood. Responsible and tightly-controlled aquaculture is the key,” Eguia added.

The war against alien invaders will drag on for decades but through steady vigilance and sound science, we can win.

Conservationists dream of an unsullied world, but the truth is that the Earth’s ecosystems are already in a constant state of flux. Since spreading out of Africa 200,000 years ago to dominate this planet, we’ve ushered in a new epoch. This is the Anthropocene, an era where the ebb and flow of life is dictated by the strongest invasive species of all.

In this globalized world, humans alone will decide whether native or invasive species will reign supreme. And though we should do everything possible to conserve native life, I cannot help but recall the words of Charles Darwin: “it is not the strongest nor the smartest species which survives, but the most adaptable.” – Rappler.com

Gregg Yan is an award-winning communicator who investigates ecological and anthropological issues in Asia. He leads the “Best Alternatives Campaign” and highlights solutions through various advocacy groups.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.