SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Inside a shanty in Barrio Tumbar hangs a graduation photo that is warped and stained from the floods that submerge this home year after year. The old woman who owns the house beams when guests say they didn’t know she had a daughter who finished college. The old woman doesn’t, but she does not deny it. She is just as proud of the girl whose smile has fused onto the glass.

Inside a shanty in Barrio Tumbar hangs a graduation photo that is warped and stained from the floods that submerge this home year after year. The old woman who owns the house beams when guests say they didn’t know she had a daughter who finished college. The old woman doesn’t, but she does not deny it. She is just as proud of the girl whose smile has fused onto the glass.

Like in many rural towns, Tumbar’s children run half-naked through its dusty dirt roads, mostly growing up to bear more children and continue this cycle. Both the velvet toga and the carefree smile in the photo are out of place in the barrio. Its subject is definitely not one of its children. I know, because the girl in the picture is me.

I was raised by my yaya Esperanza Dela Cruz in 1980s Metro Manila. Ising came to us from my father’s hometown of Lingayen, Pangasinan and took care of my parents’ home. She was in charge of housekeeping, cooking, and childcare for 4 siblings for a period spanning 30 years. As the youngest child, I was her baby and I slept by her side from infancy until the 4th grade, finally getting my own bed but only because my mother decided it was already too close for comfort. I was already calling the nanny Mommy, she let me suck my thumb till age 10, and I refused to sleep or eat without her by my side.

An outsourced love

I was my yaya’s girl. I was so frail and sickly that I was hospitalized every year, so she catered to my picky food choices and to my every ache and whimper. She would get up at midnight to cook if I said I was hungry. If I stirred in my sleep she would rock me until I dozed off. During blackouts she would fan me with an abaca fan until I fell asleep in the darkness of the tropical heat, its straw making crumpling sounds to a windy beat.

As needy as I was and as much as she spoiled me, ours was not a unique love story. Most of my peers had working mothers. At home, a spare set of arms always took care of the house and the children. It was an unwritten rule that for a salary, a yaya would be the mechanical mother, watching each child’s step and move, feeding them every meal and changing each diaper. Most yayas got past this arrangement without crossing the boundaries that are usually clear — ones that in my case, were fortunately not.

My yaya peppered me with kisses before bed and we cuddled at night as she sang me made-up lullabies. “I miss you anak,” she would say when we were apart. “I miss our loving-loving!” She listened to Johnny Midnight in the 80s and Mike Velarde in the 90s, making me drink the radio-blessed “toning water” or kiss the El Shaddai handkerchief. She taught me love in the form of tender words and the most determined kisses. She let me stir the pot of stew she was cooking, giving me credit for the dish when she was done.

Time changes love

Years passed and we all grew up, leaving Mommy unmarried and with no children of her own. When I left for college, there wasn’t much use for an older maid whose taste buds were beginning to fail. She was given a severance and let go in 1998, so she went back home to Tumbar, to the house that she built little by little with her savings, from its straw hut origins to its current half-finished, barely enclosed patchwork of steel and hollow blocks. Electricity is a luxury and water comes from a hand-pumped well in the middle of Barrio Tumbar. Day and night the old woman is alone. She grows some crops she sells at the market so she has some income.

Reminders of inadequacy

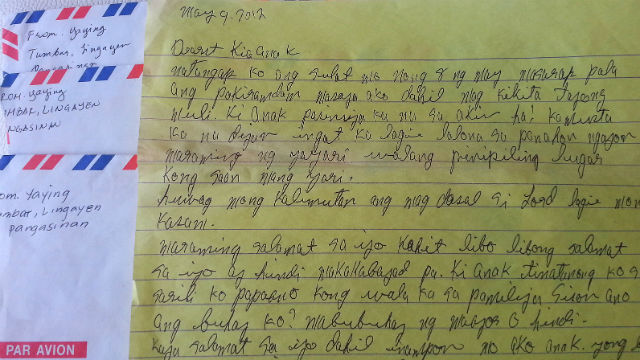

As a young adult, I made plans for Mommy that included a life with me, but in 2002 I met a vacationing New Yorker and moved to the US to follow my heart. I send her a monthly allowance she depends on, but to me it is a periodic reminder of my inadequacy. She writes me letters bearing drops of candle wax. In the part that she says she loves me, where she says how hard life is without a family, the paper is stained with tears.

In my fantasies I am home for good and I’ve taken her from Tumbar to stay with me. But my reality is limited to tearful letters in between visits whose gaps are filled with my worry. The ailments are all there now at age 70, from diabetes to high blood pressure, to random pains and bumps whose causes she’d rather not know. I heard news of her collapsing at a party and getting hit by a tricycle. In her letters, her grief echoes only into concern for me: “Anak, mahirap ang walang pamilya. Kailan ka mag-aasawa? (My child, it’s so hard without a family. When are you going to get married?)”

One more day

During my visits to Tumbar every few years, the children are still wearing our hand-me-down clothes. They chase my car and swarm the driver as he carries in the sack of rice and the boxes of groceries I’ve brought for Mommy. She offers me food and drink as I sit on the wooden plank that is her bed. She takes out her ratty photo album filled with pictures — most of which are of me.

“Kee, mahal na mahal kita. I love you and I miss you,” she says, kissing me and holding me and making me feel so, so tiny. We cry together like doomed souls, never speaking the inevitable end to our story.

Will we have another “loving-loving” day together? The time will come when the answer to this will break me. – Rappler.com

Shakira Andrea Sison currently works in the financial industry while dabbling in several unrelated projects and interests. She is a veterinarian by education and was managing a retail corporation in Manila before relocating to New York in 2002. Follow her on Twitter: @shakirasison.

A longer version of this piece, entitled The Santol Tree, is included Motherhood Statements, an anthology edited by Rica Bolipata Santos and Cyan Abad-Jugo. Released in time for Mother’s Day, Anvil Publications is launching this book on May 9, 2013, 6 pm at Bestsellers bookstore, 4th Level Robinsons Galleria. For store availability, call Anvil at +6324774752.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.