SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

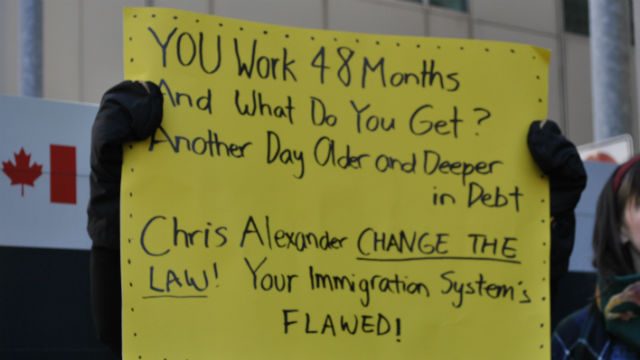

TORONTO, Canada – Migrant workers and advocates staged rallies across Canada on March 29 and 30 to call for a moratorium on the four-year employment limit for temporary foreign workers, which takes effect April 1. They also called on Ottawa to grant permanent resident status to migrant workers.

Under the controversial “4 and 4 rule,” introduced April 1, 2011, temporary foreign workers who have been working for Canada for four years or more must leave the country.

They are barred from returning to work here for another four years. Under previous regulations, workers could simply reapply for another work permit to continue their employment.

Among those affected by the new ruling, which has been described by its critics as “unjust,” are low-skilled workers employed in industries such as agriculture, fishing, food and beverage, retail, construction and personal services, including caregivers.

“Immigration officials are unable to provide statistics on the number of migrant workers due for removals as of April 1 due to time restraints, but advocacy groups estimate there could be as many as 70,000 whose time-limited work permits will expire this year,” according to the Toronto Star.

Concerns have been raised that some workers whose visas have lapsed may simply decide to become undocumented and work in the underground economy.

Currently, about 330,000 live and work under the temporary foreign worker program (TFWP), a number that has tripled in the last 10 years. Workers – many of whom are employed in Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia – come from more than 50 countries, including developed nations. The top 10 countries include the Philippines, Mexico, U.S., Jamaica, India, Guatemala, U.K., France, Korea and Ireland, according to Statistics Canada. (See related story, Facts & Figures)

Exodus

“Many of the people who are being forcibly uprooted on April 1 have lived in the country for longer than four years. They have families, friends, and relationships,” said a statement by Liza Draman from the Caregivers Action Centre (CAC). “Workers already face abuse from employers and recruiters because of bad provincial and federal laws, pulling them away from their communities on top of that is unjust, inhumane and arbitrary.”

Live-in caregivers are among those likely to be affected by the ruling, said CAC. There are about 70,000 workers classified as live-in caregivers in Canada, the majority of whom are from the Philippines and Caribbean nations.

Caregivers can apply for permanent status after two to three years, but the process has normally taken up to three years and approval hinges on a number of factors.

In October, the Conservative government announced changes to the program, making it optional for caregivers to live with their employers; it also promised to bring the backlog of 60,000 applications for permanent residence down to zero in two years. Caregivers will still wait for two years before they can file for permanent resident status, but Immigration Minister Chris Alexander said applications would be processed within six months.

In Toronto, amid blustery spring winds, workers and their supporters staged a rally at the Citizenship and Immigration Canada’s headquarters on St. Clair East. They planted seedlings symbolizing that migrant workers have established roots in their communities.

Rhea, a member of Anakbayan Toronto, a local Filipino youth organization, said she came out to support her “kababayans” (fellow Filipinos) who came to Canada to support their families and would have no jobs waiting for them back home.

Rallies were also held in Montreal, Vancouver, and in other cities in Ontario, including Guelph, Hamilton, St. Catharines and Peterborough.

‘Nonesense ruling’

Syed Hussan of the Migrant Workers Alliance for Change said the ruling does not make sense. “It doesn’t serve anyone’s purpose to remove a trained workforce, and replace it with new workers that are less aware of their rights,” he said in a statement.

“Why does holding down a job for four years result in deportation? Our communities need migrant workers to have permanent status. This mass deportation is classic economic mismanagement and is frankly irrational.”

Ottawa cited a need to “protect the Canadian labour market” as a reason for revising the TFWP. The program was only meant to address temporary labour shortages, the government said, adding that the new rule was also meant to encourage employers and their workers to seek pathways to permanent residence. Critics have noted, however, that Canada’s current immigration laws favor highly skilled workers, not low-skilled, low-wage workers.

Employers have also argued that they have had to hire temporary foreign workers because low-wage, low-skilled jobs do not attract Canadians, despite the fact that more than 1.4 million are jobless.

Canada’s unemployment rate – currently 6.7 per cent – is projected to increase following the slump in oil prices. As of February, at least 14,000 oil industry workers from Alberta and 3,000 from Newfoundland and Labrador lost their jobs, reported The Globe and Mail.

Dan Kelly, president of the Canadian Federation of Independent Business (CFIB) told The Canadian Press that new entrants to the labour market are not interested in menial, low-wage, entry-level jobs. “We have one of the highest post-secondary education attainment levels in the industrialized world,” he said.

Some businesses, including McDonald’s, are, however, under federal investigation over possible abuses of the program, following reports of locals being turned away from jobs.

Under federal law, businesses cannot hire temporary foreign workers if there are qualified Canadians available for jobs. Some economists say some industries prefer to hire temporary foreign workers because they are more compliant and are more likely to stay in the job than students or new graduates.

The Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) has been critical of the program, accusing employers and provincial governments of using it to “drive down wages, worsen working conditions, and undermine unions.” In October, following reports that some temporary foreign workers were receiving 15 per cent less than the median wage, the government required employers to pay them the prevailing wage.

CUPE also noted that these workers often have advanced education and specialized skills but are forced to migrate as “lower-skilled workers” because they are unable to get a visa in their occupation.

21st century ‘coolies’

The TFWP has also widely criticized by Canadian economists and media.

“Low-skill temporary foreign workers are the coolies of the 21st century,” wrote Calgary Herald columnist Raj Sharma. Coolies were “contract, unskilled laborers largely sourced from British India and South China,” he said.

“With the abolition of slavery in the early 19th century, corporate interests needed a cheap source of manpower. Coolies were the answer. Indentured and bonded to their employers, they were worked and, in most cases, exploited. The British Raj, limiting the length of service, imposed regulations, making the company responsible for returning the worker after the contract elapsed. Tens of thousands left their countries of origin seeking higher wages and a better life.”

Sharma added: “Then and now, such contract workers are brown-skinned and mostly Filipinos and Mexicans. Then and now, corporate interests are the same — an emphasis on cheap, reliable, compliant labour.”

More than 3,000 people have signed a petition calling on Ottawa to grant permanent immigration status on landing for low-income migrant workers, said the Caregivers Action Centre.

The CFIB, for its part, has called on Ottawa to introduce a visa that would allow entry-level workers from overseas to apply for permanent residence after two years. – Rappler.com

This story is being republished with permission from The Origami, a content partner of Rappler

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.