SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Of all the characters in the recent RH law showdown at the Supreme Court, I never expected I would admire and commend Justice Jose Perez the most.

Of all the characters in the recent RH law showdown at the Supreme Court, I never expected I would admire and commend Justice Jose Perez the most.

Amid all the tiresome and convoluted debates which include “when does life begin?” and “condoms as abortifacients,” it was Justice Perez who was brave enough to first bring up the word “statistics” into the fray (at least from how I monitored the live blogs).

Indeed, there are people (especially economists) who would prefer exploring and debating ideas while being guided by numbers and figures, instead of listening to endless ramble that resorts to rhetoric, sentiment, and opinion.

The fact is, the RH law is a well-researched and empirically-based piece of legislation grounded on an understanding of the lives of Filipinos today, especially the plight of the poor.

In what follows I will try to present a line of thinking, backed up by data, which could provide a framework by which the rationale of the RH law can be appreciated easily. In other words, we will try to extract from the statistics a story that can more or less justify why so many of us choose to have a stake in the RH law and the reforms it promises to deliver.

We start with the following:

1) The poor tend to have larger families, and they want smaller families.

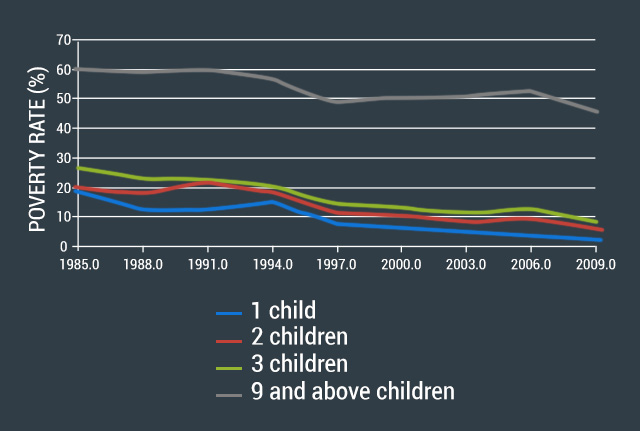

Figure 1 shows that poverty rates have declined over time across families of different sizes. However, for any given year, poverty is more prevalent among larger families (e.g., those with 9 children and above) than smaller families (e.g., 1, 2, or 3 children). We don’t know from the graph if having a large family causes poverty, or if poverty results in large families. But the data show, if anything, a strong association between large family size and poverty.

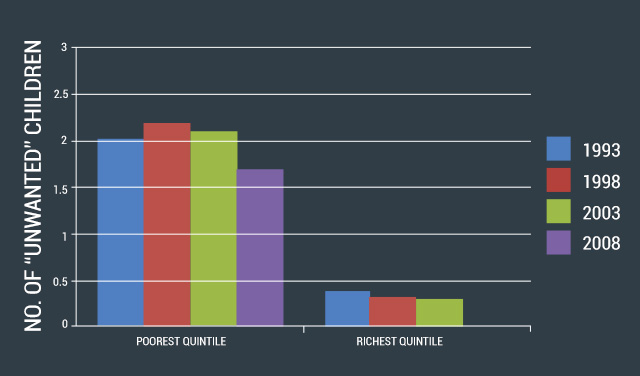

Aside from the tendency to have larger families, the poor are also the social group having the largest gap between mothers’ actual fertility and desired fertility (see Figure 2). Note that the overpopulation issue is irrelevant here. What we’re simply saying is that the poor are having more children than they desire (otherwise known as “excess fertility”) and that the rich have less of this problem.

(In fact, latest data show that the richest income group want, on average, more children than what they have, as shown by the bar in the negative region in Figure 2.)

2) The poor, who have excess fertility, also experience greater risks in pregnancy and childbirth complications.

Pregnancy is not and will never be a disease. But certain pregnancies, like those resulting from excess fertility, do result in heightened health risks during pregnancy and childbirth, even possibly leading to death. That is why there’s a case for providing health interventions regarding risky pregnancies, especially among the poor who are at risk the most.

We have seen that there is some empirical evidence that links poverty and the incidence of maternal deaths. Provinces with higher incidences of poverty are associated with correspondingly high maternal mortality rates. At the regional level, the correlation even becomes stronger and more apparent.

3) One way to prevent excess fertility and its attendant health risks is to use contraceptive methods, whether traditional or modern.

If poor women are getting pregnant more than they want to, they become more at risk of having complications in pregnancy and childbirth. Preventing excess fertility via contraception is one way of averting these complications from the very beginning.

All contraceptives, whether traditional or modern, can fail due to various reasons, including incorrect or inconsistent use. Research shows that even with perfect use (i.e., correct and consistent use), traditional methods like the calendar or rhythm methods tend to have higher failure rates than modern methods like pills, IUDs, injectables, and sterilization. By “failure” we mean the occurrence of unintended pregnancies resulting from failed contraceptive use.

Note that symptothermal or fertility awareness methods (which include the calendar, cervical mucus, and temperature methods) have a fairly low failure rate if used consistently and correctly. But that’s just it: Perfect monitoring of fertile and infertile phases of one’s menstrual cycle is prone to mistakes, misunderstanding, and miscalculations, especially if one is in the heat of the moment and it’s harder to say “no.”

Hence, to say that traditional methods are “less effective” than modern methods is a misleading and incomplete statement: It ignores the fact that traditional methods can indeed prove very effective under certain circumstances, i.e., when used correctly and consistently. Conversely, modern methods may prove more practical and effective in settings where misinformation and misuse about contraceptives in general are rife.

4) Unfortunately, the poor are less likely to use contraceptive methods across the board, whether traditional or modern.

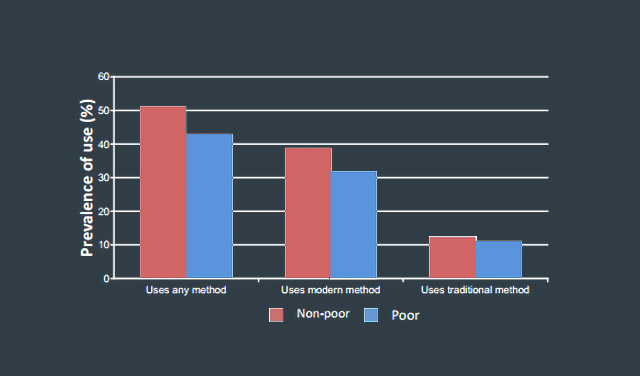

Controlling for correct and consistent use, traditional and modern methods may be on equal footing in terms of effectiveness. Unfortunately, contraceptive use in general (whether traditional or modern) has stagnated and even declined from 50.6% of the relevant population in 2006 to 48.9% in 2011. What’s more, contraceptive use among the poor (vis-à-vis the non-poor) remains lower across both types of methods.

Gaps between contraceptive use between the poor and non-poor are evident in Figures 3 and 4. Figure 3 shows that usage is lower among poor married women than non-poor married women, regardless of the method used.

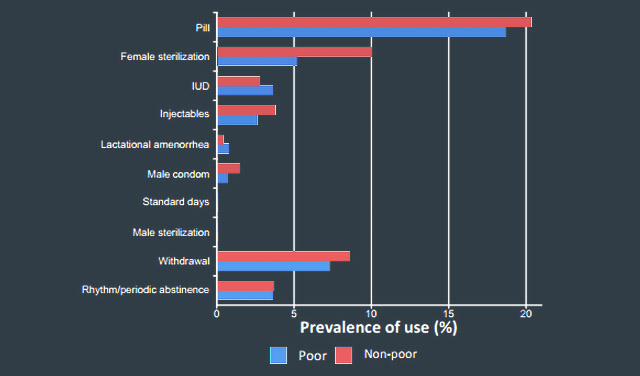

Meanwhile, Figure 4 shows that across a wide range of traditional and modern methods usage is also lower among the poor. There are some exceptions worth noting, like IUDs and the lactational amenorrhea method, usage of which are greater among the poor.

Note that traditional methods such as withdrawal and abstinence continue to be a prevalent choice of contraceptive method among the poor. Until there is a wide spread of information about the correct usage of all contraceptive types comprehensible to both the poor and non-poor, there may be a case for promoting wider access and use of modern methods over traditional methods.

5) Finally, contraceptive use is also lower for poor people who expressly want to limit or space their future births.

Unmet need for family planning services among married women of reproductive age has remained high (and has even risen) over time. (By “unmet need” we refer to currently married women not using any contraceptive method but want to plan their families either by limiting future births or spacing them.) Whereas total unmet need was 15.7% on average in 2006, it has since risen to 19.3% by 2011.

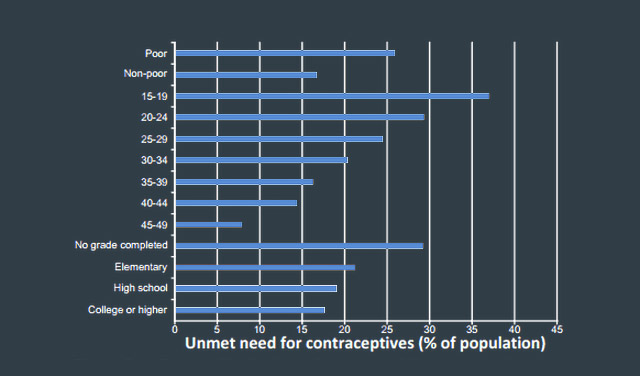

Breaking it down by demographic profile, Figure 5 shows that unmet need is especially high among 3 socio-economic groups: the poor, the young, and those with low educational attainment.

Since the income received by these groups is relatively lower than the rest of society, one might surmise that income could be a plausible constraint in contraceptive use. This is partially why the government sees it fit to assist women in the more vulnerable sectors so that they may have better access to contraceptives — whether by subsidizing costs or making health centers more accessible.

What all these mean

All in all, we can deduce from this plethora of data and research that by promoting wider and more accessible use of contraceptives (whether traditional or modern), the RH law is really just a pro-poor measure intended to help the poor not only realize their desired family size but also reduce the risks that come along with excess fertility.

Note that in our entire exposition we have made no mention or claim regarding overpopulation or population control. This goes to show that a case for the RH law can be made even without reference to these issues.

The intent of the law is simply to address the hardships faced by the poor in the primal act of reproducing, and mandate measures by which we can help them cope. That is, giving birth in the Philippines need not be excessively risky, especially among the poor. That’s all there is to it.

A final note

It is rather surprising (and frustrating) that many people still don’t get the point of the RH law, 14 years after it was first proposed in Congress. More than a decade of protracted debates have finally boiled down to oral arguments in the Supreme Court, and I’m sure that many were baffled to once again hear discussions on “when does life begin?” and “condoms as abortifacients.”

All of these moral, ethical, and philosophical debates are of course important (and some say inevitable) for a full appreciation of the RH law and its merits. However, argumentation on these issues relies on a lot of subjectivity and opinion, making them difficult (if not impossible) to resolve.

In contrast, the essence of the RH law (that of helping women achieve greater reproductive health) can be argued and justified using hard, empirical data.

Perhaps the debates could benefit from a radical shift in attention to issues that could be discussed more objectively and, hence, more fruitfully. Until then, I hope to see more people who — just like Justice Perez — introduce (or at least try to introduce) more objectivity into the proceedings through a greater dose of data, data, data. – Rappler.com

JC Punongbayan holds a master’s degree in economics from the UP School of Economics (UPSE). He is also a summa cum laude graduate of the same school. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations.

Professors of the UPSE have previously published extensively on the merits of the RH law; some related discussion papers can be found here and here.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.