SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

For the last few months there have been letters to the editor, news items, comments, and gossip, concerning something called JASMS. People who may have chanced upon these tidbits may have been wondering—what is JASMS anyway and why all the hullabaloo?

For the last few months there have been letters to the editor, news items, comments, and gossip, concerning something called JASMS. People who may have chanced upon these tidbits may have been wondering—what is JASMS anyway and why all the hullabaloo?

Frankly, I don’t know what JASMS is but I know what it was.

JASMS is the acronym for Jose Abad Santos Memorial School—named after the former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, who said to his son as he was about to be executed for being unwilling to pledge allegiance to Japan, “Do not cry, Pepito. Show these people that you are brave. It is a rare opportunity for me to die for our country. Not everybody is given that chance.”

Chief Justice Abad Santos was also the Chairman of the Board of the Philippine Women’s University.

In 1948, Doreen B. Gamboa, British by birth and a Filipino by citizenship, thought it fitting to name the school that she was about to set up, after the Chief Justice. She had just arrived with a Master’s Degree from Mills College in the United States and was given the mandate by PWU with whom she had been connected since the early ’30s. She had helped set up one of the first pre-schools in the Philippines and had been working with Filipino children for many years. When she came back, she was determined to set up the kind of school that she believed Filipino children deserved—very different from other schools.

In 1948, Doreen B. Gamboa, British by birth and a Filipino by citizenship, thought it fitting to name the school that she was about to set up, after the Chief Justice. She had just arrived with a Master’s Degree from Mills College in the United States and was given the mandate by PWU with whom she had been connected since the early ’30s. She had helped set up one of the first pre-schools in the Philippines and had been working with Filipino children for many years. When she came back, she was determined to set up the kind of school that she believed Filipino children deserved—very different from other schools.

To make a long story very short, she battled for many years to set up the kind of school she wanted. She battled parents who thought their children would not learn anything (I will explain why later), she battled government bureaucracy so afraid of change, she battled teachers set in their ways, and she battled the Catholic Church which considered her methods communistic if not atheistic. But she had the support of the president of the Philippines Women’s University—Dr. Francisca Tirona Benitez and her husband and Chairman of the Board of PWU Dr. Conrado Benitez.

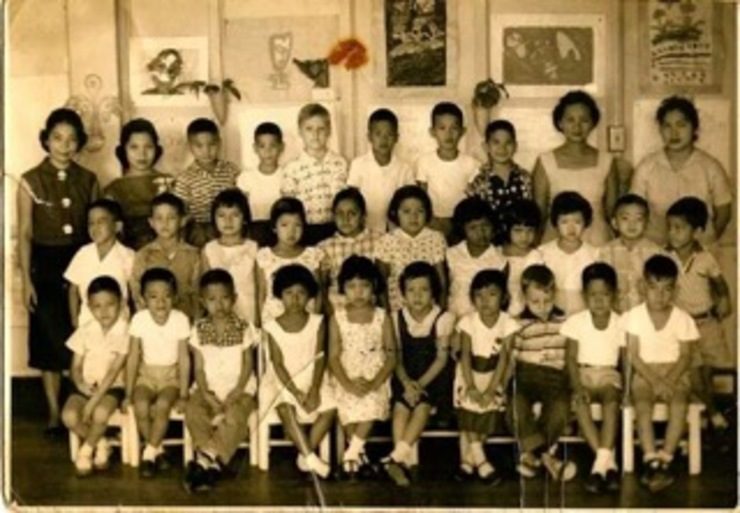

LIttle by little she got her way and earned the trust of more and more parents and JASMS on Taft Avenue continued to grow. She trained a group of teachers who understood her methods and what she was trying to achieve.

In 1954, the Philippines American Life Insurance Company which had built the first housing development in Quezon City, offered PWU a lot adjacent to the housing development on the condition that it be used for a school which was a requirement of the then Philippine Homesite and Housing Corporation. PWU then built a school on Mrs. Gamboa’s specifications and this became JASMS Highway. Some years later a high school was built.

Dream school

JASMS Highway was all that Mrs. Gamboa had dreamed of for a school. Classrooms were big and airy. Hallways were wide and open. The preschool classrooms completely opened into their own playground area. There was a big auditorium and gym. There were grounds big enough not only to accommodate sports and games but to allow the creation of the “JASMS Farm.”

“The Philippines is an agricultural country. City children need to know about agriculture.”Mrs. Gamboa said. So there were rice paddies, vegetable plots, fruit trees and a pond for fish.

The children learned to manage the farm. They learned to market their produce. They learned to take losses when the weather was not right. They learned the problems of the farmers first hand. The pond and garden were also sources of material for science projects.

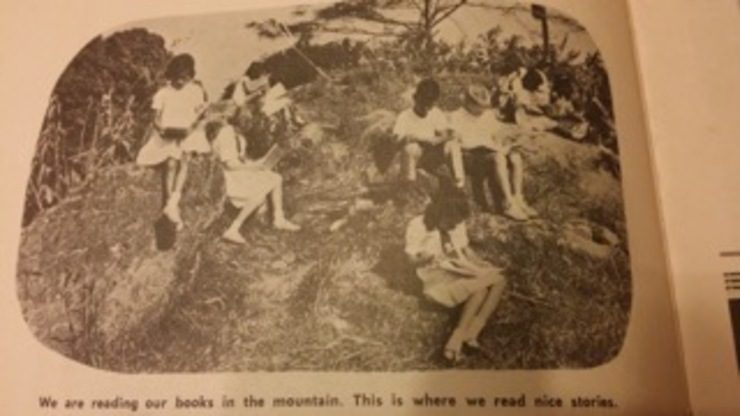

Then there was “The Mountain,” a big pile of rocks and adobe on which grass and wild flowers grew and which provided the back drop for many dramatic presentations and celebrations.

What made it different

So what was so special about the school? I will not go into details of Mrs. Gamboa’s “method.” But here are some of the things that made it different.

No matter what grade, reading, writing, and mathematics were not taught as separate subjects but integrated into the particular “unit of work.” Resource persons and field trips were used extensively.

There were no entrance examinations and definitely no entrance examinations for (good grief!) kindergarten children. Mrs. Gamboa believed all children deserved a good education.

There were no desks in the classrooms. Only tables so that students—no matter what age or grade—could sit around and discuss their “unit of work.” Each classroom had its own book shelves where the teacher would put reference books and other materials for easy access on the particular topic of discussion. There were blackboards all around and bulletin boards and space for “projects” to be set up.

There was no competition for grades—students worked according to their own abilities, each contributing what he could to the project. Students better endowed helped those who had less ability.

In other words, children learned to take care of each other.

Actually, there were no grades given. Students were evaluated on the basis of what they accomplished versus what they were capable of accomplishing. Only the Bureau of Education (as it was known then) knew what numerical grades they had been given.

There was no homework. (Ah, this really got the parents worried.) Mrs. Gamboa believed that a whole day in school should be enough and that home time should be spent enjoying the company of parents and siblings and resting—this being good for mental, emotional and physical health.

Teachers were there only to guide and to see that the right materials were available to the children. Children were encouraged to seek knowledge not have it rammed down their throats. This, some people considered as “lack of discipline.” Yet, a teacher could leave the room and the children would continue working on their own as if she was there.

Mrs. Gamboa wanted children to grow up in a democratic classroom so that they would learn first-hand to be citizens in a true democracy.

There was always library time with a big library with books on open shelves so that the children could browse and a friendly librarian to help find materials the student needed.

I could go on but the main thing was the children loved going to school. And they learned to love learning.

Effective?

But was this kind of education effective?

Well, to my knowledge, graduates of JASMS elementary school had no trouble getting into and doing well in “traditional” high schools. All JASMS high school graduates who wanted to get into the University of the Philippines, did so. JASMS alumni include doctors, nurses, scientists, teachers, visual artists, musicians, businessmen, and other professionals.

Also, most important, JASMS students learned to care for others besides themselves. And this, I think, is what Mrs. Gamboa wanted most of all for them to learn.

Now back to the present. First, why do I not know anything about what JASMS is today?

It’s because I turned away. I had to watch Mrs. Gamboa, my mother, suffer as she watched her beloved school begin to change. The struggle to keep class sizes small; teachers’ salaries commensurate with the work load, ability, and experience; and tuition fees at a level that would not exclude the less financially able—became harder and harder.

Then a building was built for a nursing school and she saw further encroachment as the University required classrooms to be used for adult evening classes.

Then she became ill and when she died in January 1977 it was too painful for me to become involved with JASMS. And so I never knew what was happening.

I know some of her teachers managed to keep it going for many years. And then one day I heard that something had happened to the property and only a small portion was left. The Mountain was gone. The Gym was gone. The soccer field was gone. The Farm had been long gone.

The preschool classrooms were gone and the whole school occupied only what was once the high school. Most of the original teachers had died or retired.

Struggle

JASMS still struggles to exist—mostly, I think, because alumni and parents still are grateful for what the school did for them and for their children.

They do not believe that a school like JASMS should be allowed to just disappear. (READ: Save the Philippine Women’s University)

My daughter, Gillian, brought up in JASMS, who absorbed much of what her grandmother was, gave up a high-paying corporate job to try and rebuild JASMS. She is braver and a much better person than I am.

I don’t know what will happen.

Land values are land values. Perhaps it’s too much to hope that education might be considered of some value as well—specially the kind of education that JASMS offered; specially the kind of education that this country so desperately needs. – Rappler.com

Joy Gamboa Virata is a respected thespian and theater director. She is the founder and artistic director of Repertory Philippines.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.