SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines (UPDATED) – It’s been a tough year for Ombudsman Conchita Carpio Morales and her band of anti-corruption prosecutors. Set to retire in 2018, Morales is seeing major corruption cases being dismissed, even as information about where the money went or who stole it remains unknown.

It’s robbery with a nameless thief – mind-boggling to the ordinary taxpayer, but painful for the Office of the Ombudsman, which investigated and prosecuted these cases for years, only to see the suspects walk free in the last 12 months.

The tough year began on July 19, 2016, when the Supreme Court (SC) acquitted the Ombudsman’s biggest fish at the time – former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.

PCSO fund scam

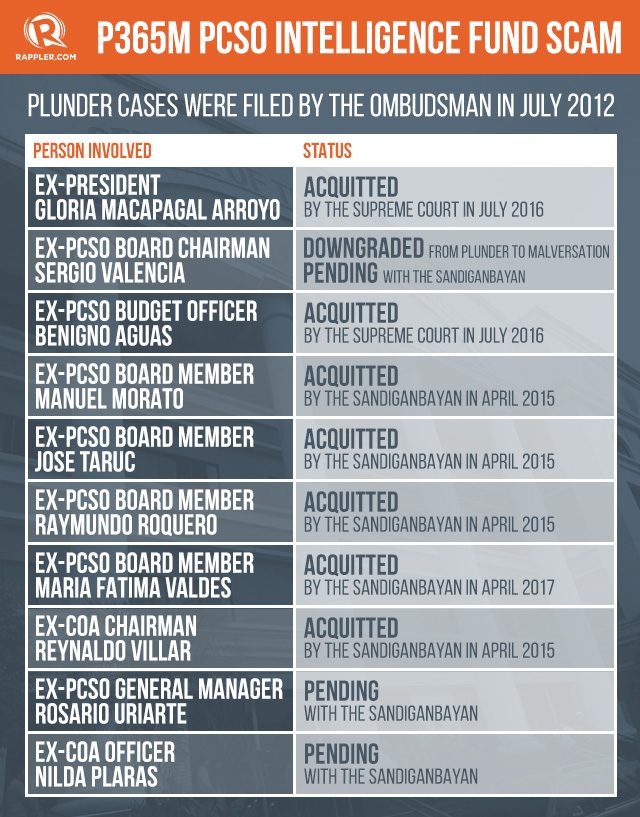

Arroyo and 9 others were accused in 2012 of plundering more than P365 million in Philippine Charity Sweepstakes Office (PCSO) funds, but each of the accused got away as years passed that, by this time, only two were facing charges, with one of them managing to have his alleged offense downgraded to the bailable malversation.

The Arroyo acquittal was controversial, although it wasn’t so much of a split for the magistrates of the High Court with only 4 justices dissenting: Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno, Associate Justice Marvic Leonen, Associate Justice Benjamin Caguioa, and Arroyo appointee, Senior Associate Justice Antonio Carpio.

Why did this scam case fail? As in all dismissed cases, the blame is on the prosecution – the Ombudsman prosecution.

The issue was that, from 2008 to 2010, PCSO officials diverted a total of P365 million to their intelligence fund, which can be accessed and withdrawn anytime with minimal restrictions.

It was former PCSO General Manager Rosario Uriarte who asked additional intel funds from Arroyo, who approved them. The approval was supported by resolutions, which were passed by the board members who would later be accused as well.

According to lawyer and accountant Aleta Tolentino, chair of the PCSO audit committee who was used as witness by the Ombudsman, the cash advances made by Uriarte exceeded the allowable amount. Citing PCSO charter, Tolentino said the operating funds were the only allowable source of intel funds. In this instance, however, it was impossible to have gotten the intel funds from there because PCSO’s operating funds were already on the negative at the time.

Uriarte and others took the money from the prize and charity funds – the funds used to pay sweepstakes winners and provide for the agency’s charity work, which is its core purpose.

Ombudsman investigators found more irregularities: these cash advances were not properly liquidated and they didn’t specify projects and beneficiaries. Worst – at least for Arroyo – the approval was sought directly from the President without going through the layers of the social welfare and health departments, which have direct control and supervision over the PCSO by virtue of a 2005 executive order.

What the SC ruling says

Arroyo’s implication in all of this is that she wrote “OK” on the margin of Uriarte’s letter-requests for additional intel funds. But the High Court said it was not an overt act of plunder because it is a “common legal and valid practice of signifying approval of a fund release.”

The SC also asked: where is the money? If prosecutors couldn’t produce physical evidence that at least P50 million, the treshold for plunder, went into Arroyo’s hands, then she’s not a plunderer.

The SC, in fact, also doubted that the case was one of plunder. For the magistrates, a conspiracy must have a mastermind, a main plunderer. Because the prosecutors did not name a main plunderer, it could therefore be assumed they all benefitted equally. So if you divide P365 million by 10 – the number of accused – that would mean each of them only got P36 million each and that is lower than the plunder treshold of P50 million.

The SC also dismissed the prosecutors’ argument of command responsibility – the fault of subordinates, the fault of their boss. The tribunal said it is “legally unacceptable” to apply the doctrine of command responsibility to Arroyo because it only pertained “to the armed forces or other persons subject to their control in international wars or domestic conflict.” The scam was not a case of war, the SC pointed out.

The PCSO board members issuing resolutions that certified the cash advances was not enough for the anti-graft court Sandiganbayan to say there was conspiracy among them.

Dissenters in the SC took issue with the majority decision. Sereno said the need to identify a main plunderer was not contemplated by the plunder law, effectively saying the High Court introduced a new legal principle.

Associate Justice Estela Perlas Bernabe, who concurred in part and dissented in part, warned that the SC decision would now require proof of the money although thieves are very likely to hide them well.

Leonen had biting words: “The scheme is plain except to those who refuse to see.”

Uriarte, who evaded her charges for 4 years, had been described as the missing link who supposedly could pin down the former president. That did not happen. Uriarte is the remaining PCSO official facing plunder, and she has a tough road ahead because she was the one who asked for the cash advances.

It remains to be seen if the SC decision on Arroyo would help Uriarte’s case, but there are windows of opportunities for her in the ruling.

For example, the SC said “Uriarte’s requests indicate their compliance with the Letter of Instruction (LOI) 1282.” LOI 1282 is a memorandum from the Marcos years which laid down rules for intelligence funds, and which prosecutors said Uriarte violated when she sent her letter-requests to Arroyo.

The SC said: “According to its terms, LOI 1282 did not detail any qualification as to how specific the requests should be made. Hence, we should not make any other pronouncement than to rule that Uriarte’s requests were compliant with LOI 1282.”

Fertilizer fund scam

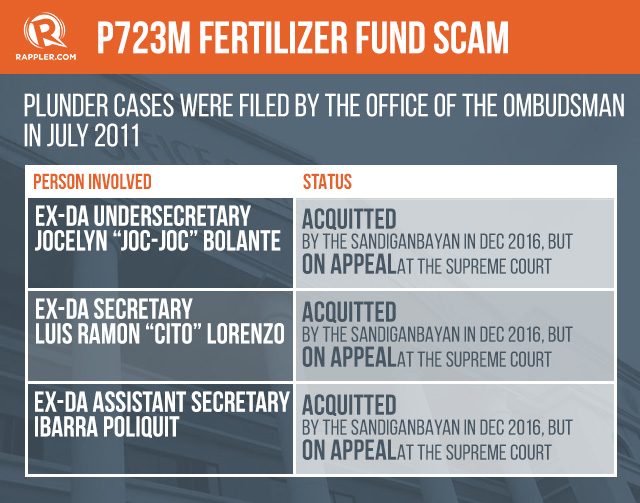

Then there is the fertilizer fund scam: P723 million was allegedly misused in a scheme that involved officials of the Department of Agriculture (DA) and local executives. The speculation was, the funds were used to help finance the political allies of Arroyo in the 2004 elections.

In 2011, the Ombudsman accused former DA Undersecretary Jocelyn “Joc-Joc” Bolante of orchestrating the scam, which involved buying overpriced fertilizers and implementing ghost projects in connivance with foundations – a scheme similar to the now familiar pork barrel scam.

The Sandiganbayan cleared Bolante twice, as well as his co-accused former DA Secretary Luis Ramon “Cito” Lorenzo Jr and former Assistant Secretary Ibarra Poliquit. The court handed the acquittals without even issuing any warrant of arrest.

Bolante was accused as mastermind because he requested the funds from the budget department on behalf of the DA. He also submitted the list of project proponents, which were found to be unqualified. Ombudsman investigators said Bolante was not diligent in monitoring his projects, “which resulted in the misappropriation, re-alignment and diversion of fertilizer fund to other purposes.”

The Ombudsman calculated P56 million in fertilizer funds that it could no longer find now. This became its basis for charging him with plunder, but for Sandiganbayan, the evidence was too weak.

“Contrary to the musings of the prosecution, we find nothing substantial therein that would change our view as to the lack of probable cause for plunder in this case…. No material participation, other than the release of the funds, could be shown to be attributable to accused Bolante,” said the anti-graft court.

Ombudsman Morales is not backing down, however. She has elevated this case to the SC, and called the Sandiganbayan decision “unreasonable” and “erroneous.”

Inordinate delay

The P723-million fertilizer fund scam is made up of separate cases involving the same scheme. But they are only graft cases against local officials because the amounts involved, taken individually, do not reach the P50 million plunder treshold.

Even as graft cases, they are still being dismissed one by one. Introducing: the doctrine of “inordinate delay.”

At least 4 other fertilizer fund scam cases have been dismissed since 2016 because, the Sandiganbayan says, the Ombudsman took too long investigating and prosecuting them. This violated the rights of the accused to a speedy disposition of cases, it said.

This issue has been the subject of conflict between the Ombudsman and its supposed partner in fighting corruption, the Sandiganbayan. Morales questioned the anti-graft court justices before the SC, with a prayer of striking down the doctrine, or at least amending it so that the Ombudsman’s cases are not dismissed just because there are delays in the investigations.

Morales also sent a letter to Sandiganbayan Presiding Justice Amparo Cabotaje-Tang to seek her consideration – but the anti-graft court continues to heed the inordinate delay doctrine.

The most recent case to fall apart due to inordinate delay was the P6-billion debt deal between Philippine National Construction Corporation (PNCC) and British lending firm Radstock. The debt agreement was ruled unconstitutional by the SC in 2009, and subsequent graft complaints were filed with the Ombudsman in 2010.

Using the delay doctrine, 12 officials were acquitted in April 2017, inspiring one of the accused, former government corporate counsel Agnes Devanadera to use the same argument. She had previously challenged evidence, but when her co-accused were acquitted because of the delay doctrine, she dropped her earlier argument and used this.

First Division Justice Geraldine Faith Econg even asked Devanadera in open court: “Are you a Johnny-come lately?” but still proceeded to acquit her barely a month after.

This may just be the biggest problem of the Office of Ombudsman today. Based on its own data, from January 2016 to May 2017, a total of 79 cases were dismissed because of inordinate delay. (Cases against different individuals and different counts from the same incident were counted separately.)

A total of P7 billion is involved in all these dismissed cases, although the Ombudsman’s office clarifies it does not necessarily mean it is the same amount it could have recovered as civil indemnity. In some cases, investigators explain, the issue is the shortcut in the process: the projects are there, they see where the money went, but there was anomaly in the transactions, most of which have something to do with skipping public bidding.

Morales: 10 lawyers vs 100

The Office of the Ombudsman has taken its battle with the Sandiganbayan to the High Tribunal, accusing the anti-graft court of being inconsistent with their rulings.

“With all due respect, the refusal of Sandiganbayan to acknowledge the Ombudsman’s limitations is bordering on the unfair and unjust…. We continue to file informations under a cloud of uncertainty because of lack of clear and firm guidelines as to how Sandiganbayan interprets and appreciates the legal concept of inordinate delay,” the Ombudsman said in its SC petition.

Morales, who does not freely give media interviews, felt compelled in April to call a press conference – with two executives in tow – to lengthily discuss this issue with the media. Corruption is a hard crime to prove, they said, so the fact-finding phase should not be included when counting delay. This is also what they’re asking the SC to consider.

The office also grapples with the lack of manpower, with some prosecutors being recruited to be trial court judges. Hiring is continuous, according to the office, but Morales said in April she would stay picky: “It’s difficult to hire lawyers because we’re very strict. I’d rather have 10 lawyers who are competent than 100 lawyers who are insufficient and lazy.”

In that press conference, Morales defended her prosecutors, and said their cases were not weak. “We cannot be reckless, we see to it that when we file a case, we see to it we are loaded with ammunitions to defend our case,” she said.

While it may appear now that they are running out of ammunition, Morales is stepping on the gas for her last 12 months as Ombudsman – despite the threat of an impeachment case. “Good luck!” she tells her critics.

“We are in our penultimate race,” said Morales, this time referring to the pork barrel scam, now the Ombudsman’s biggest case, perhaps the biggest in the history of the agency.

But movements, especially in the Department of Justice (DOJ), seem to attempt to shake even this. Justice Secretary Vitaliano Aguirre II himself has expressed leanings toward making alleged mastermind Janet Lim Napoles a state witness.

Aguirre has called for a reinvestigation and has even made statements to the effect of wanting to take over the prosecution, although he admits it’s Morales who has jurisdiction.

Morales is fierce as always. In May, she said: “I’m not bothered at all. We are confident of our position. Whatever they say, let them say.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.