SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – For many Filipinos, Sept 26, 2009 will always be a day to remember.

It was a time of hopelessness, when in a flash, lives, property and livelihood were swept away by a monstrous deluge. It was also a time of courage when the same disaster inspired equally awesome acts of heroism and selflessness.

On that day, Tropical Storm Ondoy (it was not even a typhoon) battered Metro Manila and nearby provinces, even affecting Regions XI, IX, XII and the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao.

It let fall a record amount of 455 millimeters of rain for 24 hours straight, almost one-and-a-half times the historical average for the month of September from 1998 to 2008.

By the time it left the Philippine Area of Responsibility the next day, it left more than 400 people dead from floods and landslides and damages worth P11.12 billion, according to the National Statistical Coordination Board.

The Philippines can expect more disasters like Ondoy to strike in the future. The Philippines is the 3rd most disaster-prone country in the world, according to the World Disaster Report 2012. A Maplecroft study ranks the Philippines 6th in the list of countries most vulnerable to climate change impacts, which include extreme weather conditions.

Readiness

So is the Philippines ready for another Ondoy?

Lucille Sering, Secretary of the Climate Change Commission, said the government has taken steps to better equip the country for the next deluge. Many of these steps are rooted in learnings from Ondoy and Pepeng, the two major calamities in 2009 that inspired the creation of the Commission in the first place.

What has government done since Ondoy? Here are 5:

1. More collaboration and coordination

A major learning from Ondoy is the need for more coordination between government agencies, civil society and other sectors.

“The thing we most learned is that the programs of government need to be cross-sectoral. There is a need for everyone to be involved. Most government plans then were sectoral, the agriculture sector would focus on agriculture alone. But we came up with a plan that is thematic,” said Sering.

That plan is the National Climate Change Action Plan or NCCAP, a comprehensive plan that lists steps for an integrated approach to adapt to climate change and mitigate its adverse impacts. The plan puts heads together. It involves 23 government agencies, local government units, the academe, business sector and non-governmental organizations.

Read the NCCAP Executive Summary here.

All these sectors must collaborate to find solutions to 7 priorities set by the NCCAP: food security, water sufficiency, environmental and ecological stability, human security, sustainable energy, climate-smart industries and services, knowledge and capacity development.

2. Vulnerability assessment

Disaster rehabilitation funds that go to repairing damaged property and providing for the needs of evacuees and disaster victims has increased by 26% from 2008 to 2012, bemoaned Sering. The rate is even higher than the increase in the calamity fund itself which is just 6%.

“We are saving lives yes, but we are increasing expenditure. What we want to see is an infrastructure development wherein even under circumstances of extreme weather, we lessen evacuation. That’s the idea of climate resiliency.”

The best way to lessen expenses on disaster rehabilitation is to prepare for the disaster way ahead. To do that, communities must be able to assess where storms will hit them hardest. This is where mapping comes into the picture.

Advances in mapping technology now allows maps to show specific impacts of climate change in a given area.

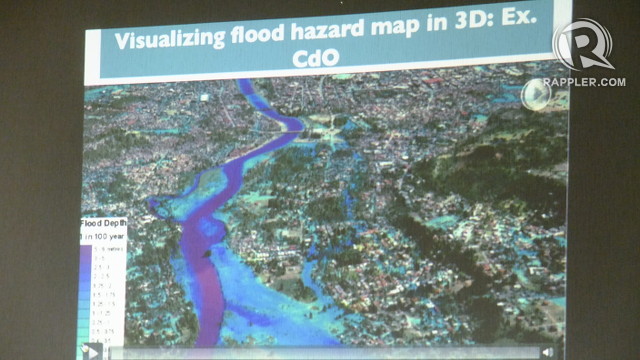

Three-dimensional mapping called the Disaster Risk and Exposure Assessment of Mitigation Light Detection Ranging or DREAM LiDAR project allows people to see what will happen to a flood-prone area the next time disaster strikes.

Aircrafts with built-in LiDAR equipment hover over the area. The LiDAR equipment then emits light pulses which generates data about the area, producing high-resolution maps of, for example, watersheds, rivers and potential flood zones.

The data can tell LGU officials which residential areas should be evacuated or, looking ahead, which areas will not be good for investment because they are flood-prone.

With the help of the Department of Science and Technology, the Climate Change Commission completed the first 3D map showing the 2020 and 2050 rainfall scenario for Cagayan de Oro, one of the worst-hit cities during Typhoon Sendong in 2011.

READ: Climate Change Commission unveils first climate change map

But Metro Manila, Ondoy’s main victim, does not have this kind of map yet. However, the geohazard map the megacity does have is good enough for disaster management, at least, in the short term.

The DREAM LiDAR map costs P5 million-P10 million to create, according to Sering. If enough sectors put their heads and wallets together, any community can get this kind of map for themselves. It may be pricey but Sering said, “It’s nothing to the cost of damage. I call it defense of expenditure.”

3. Going local

Another realization from Ondoy, said Sering, is the need to customize disaster preparation plans to the specific and unique circumstances of each community.

“What’s applicable in Albay may not be applicable in Cebu. The requirement of the law (Climate Change Act of 2009) is for us to do local climate change action planning.”

And so the Commission set out to form Eco-towns, or demonstrations of climate-resilient towns that would serve as models for other local government units. Under the Eco-town Framework, LGUs can ask the Commission for assistance in creating plans to make their communities better prepared for the effects of climate change. These effects include impact on agriculture, water sufficiency and environment, aside from disasters.

Siargao, a teardrop-shaped island off the coast of Surigao del Norte, became one of the pilot areas for the Eco-town project. One of the best surf spots in the country because of its proximity to the Pacific Ocean, it is the most vulnerable to tsunamis for the same reason. It is also among the poorest communities in the country, according to NSCB.

The Commission gave them their first geohazard map. Before then, they only had crude table maps as their basis for city projects and development. With the help of the geohazard map, the local government was able to identify risk areas and assess their natural resources. They saw that without their mangrove forests, one of the country’s largest, they will be very vulnerable to tsunamis and floods.

Immediately after, the local government passed an ordinance to protect the mangroves and marine protected areas.

The map and other data gathered by the Commission brought attention to the fact that the community’s investment in agriculture did not bring back returns. Storms wipe out crops at an almost regular basis, emptying their coffers and making them more dependent on the national government for money.

“What we are doing is helping them know what activities in their area they can earn from because that’s where they should be investing. They have to diversify,” said Sering.

Other Eco-town demonstration sites are San Vicente in Palawan, Eastern Samar, Batanes and the Upper Marikina River Basin.

4. Alleviating our cities

“I don’t think Metro Manila is ready for another Ondoy.”

Sering said that highly urbanized areas are the most vulnerable to disasters. Our cities have become concrete jungles where the dearth of absorbent soil and trees makes water run-off from rain accumulate faster, leading to floods.

A study by the Metro Manila Development Authority after Ondoy showed that the megacity’s drainage system is not able to absorb water run-off. Extreme weather conditions add even more water, overwhelming the system.

A cabinet cluster in the Climate Change Commission which includes the MMDA and Department of Public Works and Highways is trying to address the problem.

“There is an aggressive push for clearing waterways. We see more dredging being done now,” added Sering.

But one major problem the initiative faces is that aside from informal settlers blocking waterways, there are legal structures there too.

“Any small amount of land that you take away from your river will raise the water level in times of extreme rainfall.”

Another strategy being pursued by the Commission is to decrease the urban population. Rural-to-urban migration has led to over-populated cities. But the reason why people from rural areas choose to leave their hometowns for the big city is poverty.

“There’s urban migration because there are no jobs available. Even schools there offer IT and criminology. Agriculture is not glamorous for them. It’s like you’re ready for poverty if you’re in agriculture,” explained Sering.

That’s why the Eco-town Framework is being applied to the poorest provinces first. Priorities targetted by the framework include protecting the agriculture and fisheries sector in the provinces to provide sustainable livelihood for the people. If they’re making enough money where they are, they won’t see the need to move to the city.

The framework is also strengthening health and social services in rural areas so that residents don’t need to go to the cities to avail of them.

5. Early warning systems

Another tool we have now is Project NOAH (Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards), a project under the DOST which aims to use advanced technology and innovative information systems to prevent and mitigate disasters.

NOAH projects include the DREAM LiDAR mapping, enhanced geohazards mapping, Landslide Sensors Development Project, Storm Surge Inundation Mapping Project and Weather Information Integration for System Enhancement or WISE.

It aims to install 600 automated rain gauges and 400 water level measuring stations in 18 major river basins in the country including the Marikina River Basin, Cagayan de Oro River Basin, and Iligan River Basin. These basins are closely watched during typhoons and storms as their water level rise prompts massive evacuation and contributes to flooding in nearby areas.

All these efforts are meant to provide vulnerable communities a 6-hour lead-time warning against impending floods.

“The early warning system gives us more time to leave the house. If we cannot catch up with infrastructure, at least we can do better in our early warning system. Our priority now would be how to save lives,” said Sering.

Learning from memory

Though Ondoy is one of the most traumatic disasters to hit the Philippines in recent years, an older storm remains the most vivid in Sering’s mind. In 1984, her hometown of Surigao del Norte was devastated by Typhoon Nitang. It was her experience of Nitang that motivates her to help combat climate change.

Learning from Nitang has made Surigao del Norte one of the few disaster-ready provinces in the country, according to the Commission’s assessment.

“We’ve adjusted through time. We learned from it. Until now, even high school and college students know about Nitang. We really passed it on. You don’t take this for granted. We keep it alive in all our stories and we try to remember it constructively,” said Sering.

Perhaps the rest of the Philippines can take a page from Surigao del Norte’s book. Perhaps the best way to make the most of a tragedy like Ondoy is to remember it and keep its story alive. – Rappler.com

Marikina days after Ondoy image from Shutterstock

Imelda Avenue after Ondoy image from Shutterstock

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.