SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

ZAMBOANGA CITY, Philippines – I arrived in this city on the 6th day of the siege that began on September 9 when Moro National Liberation Front fighters occupied coastal villages and demanded to be allowed to hoist a flag of independence at the city hall.

The images I saw everyday in many ways reflect the reasons why conflict in Muslim communities persist to this day. There was blood, fighting, faith. There were poor villages, decrepit houses, the unemployed, and old folks who feel they have been ignored by the government. There were real images of grief, there were photo-ops by public officials.

Here’s my recollection of those days:

Sept 14: Getting my feet wet

My first assignment was to visit the evacuees at the Joaquin Enriquez Memorial Sports Complex. I thought it was an easy task since I’m quite familiar with scenes in evacuation centers every time calamities strike Metro Manila. But this one was different. It was like two typhoons hit one city in a single stroke!

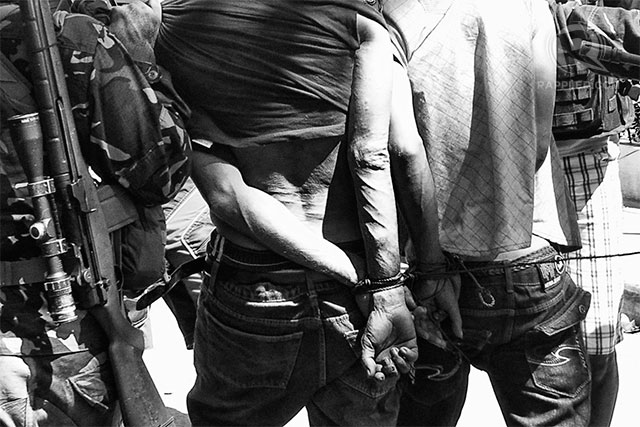

After lunch, I proceeded to the war zone in Sta. Catalina. It was quiet there compared to the day before. I saw a group of soldiers dragging 2 men —bloodied, bonded and blindfolded. The men identified themselves as hostages, but the soldiers insisted they were MNLF fighters.

Just a few blocks away from Sta. Catalina is the city proper. It is the center of commerce, governance, leisure, and education in the whole Zamboanga peninsula. I saw a Philippine flag in front of the city hall, but there was no sign of any human activity in the surrounding areas.

Sept 15: Sunday, bloody Sunday

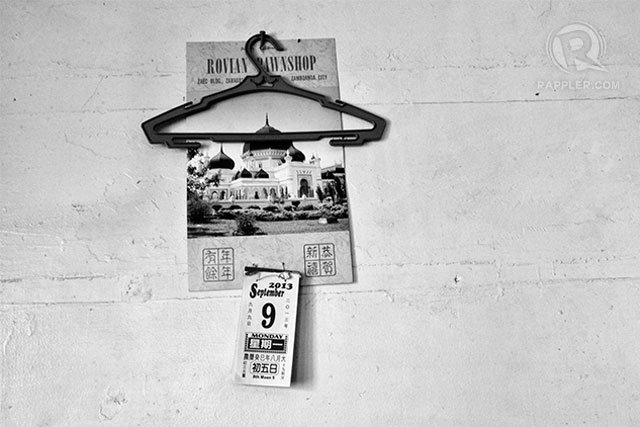

Government forces retake Sta. Barbara Elementary School. A calendar inside a police precinct identifies Sept 9 as the start of the standoff.

Pilar Street connects Barangays Sta. Catalina and Sta. Barbara. Here I saw, for the first time, dead MNLF fighters. It was reported that they died before midnight of Sept 14.

Zamboanga City is predominantly a Catholic city. I visited the cathedral, hoping to see people praying for peace. But to my surprise, only a few residents were there. Fear continues to grip the city.

Sept 16: Raining mortars

There was definitely no sign of the ceasefire supposedly agreed upon between MNLF’s Nur Misuari and Vice President Jejomar Binay. Task Force Zamboanga forces fired mortars one after the other, targeting suspected MNLF strongholds in Sta. Barbara and Sta. Catalina.

That afternoon, 2 MG520 choppers dropped bombs in a fishpond at Barangay Rio Hondo, where suspected MNLF leader Habier Malik was reportedly hiding. The attack yielded no rebels — dead or alive.

Towards the end of the day, an improvised bomb blew up a car parked at a residential street in Barangay Camino Nuevo. No one was killed. The military dismissed the incident as a diversionary tactic of the MNLF.

Sept 17: Freedom, reunions

A huge batch of civilian hostages escaped their fleeing captors that morning. They underwent processing and debriefing inside Camp Batalla in Barangay Cawa-Cawa, and were reunited with their families in the afternoon.

It was reported that Zamboanga City police chief Jose Chiquito Malayo was held hostage by MNLF rebels in Barangay Mampang. Before sundown, Malayo was on board a bus en route to the Western Mindanao Command headquarters with his alleged abductors who supposedly surrendered to him. The day before I left the city, troops manning the mangroves in Barangay Talon-Talon surprised me with cellphone videos of what transpired: there was no hostage taking and it looked like no surrender happened, at least in that area.

I was able to sneak into the now famous Lustre Street of Barangay Sta. Catalina. Here I saw the destruction caused by the standoff. Empty shells of bullets littered the ground, houses were in ashes, and the remaining structures were riddled with bullets.

In contrast, the scenic beauty of the Zamboanga Bay sunset hides the chaos and uncertainty.

Sept 18: Confusion

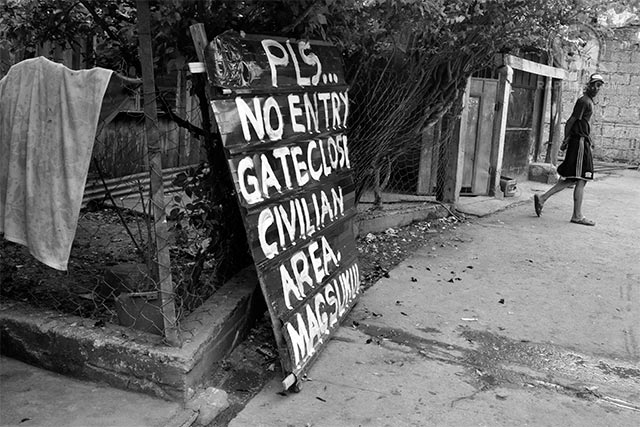

With the surrender of some MNLF members and the release of hostages, people thought that the standoff was over. But not in Barangays Mampang and Arena Blanco. Here I saw people boarding assorted vehicles to flee persistent street battles in their area.

Back in the pueblo, I see signs of normalcy. The city’s temporary market is full of people buying food supplies. Shops and financial institutions open for a limited period of time but a few steps away, streets leading to the war zone remain a ghost town.

Sept 19: ‘Normalcy’ restored

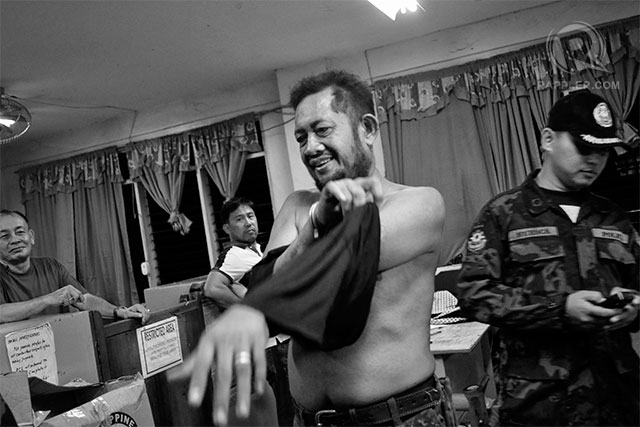

On this day, the Zamboanga International Airport reopened. The authorities also regularly present to the media batches of MNLF fighters who have either surrendered or were captured. Some evacuees begin to return to their homes.

“Normalcy” is disrupted by big fires and sporadic gunshots from the war zone.

Sept 20: Friday prayers

Muslim evacuees inside the Joaquin Enriquez Memorial Complex hold a high noon Friday Prayer in a makeshift mosque.

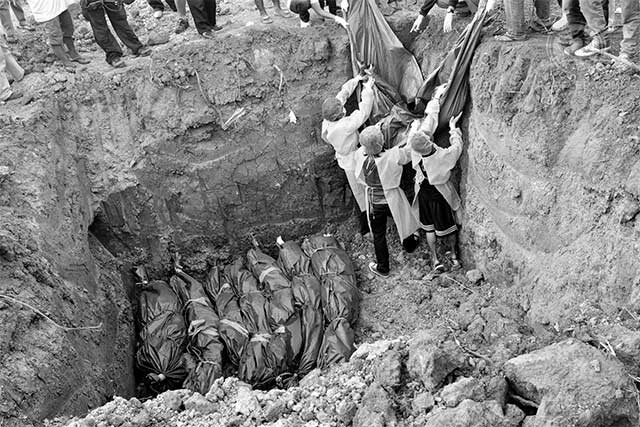

In a vacant lot in Barangay Mercedes, 8 MNLF fighters who were killed in battle were buried without the Muslim tradition. At least 45 kilometers away from the mass grave, an improvised explosive device kills 3 civilians in a bus terminal in Barangay Lamuan.

Sept 21: Revelation

Released hostage Fr. Michael Ufana holds a mass with his fellow hostages at the St. Joseph’s Parish. In a press conference he recalls his ordeal as a “negotiator” and captive of Habier Malik. He then revealed a missed opportunity – when government turned down Malik’s demands in a negotiation that could have ended the crisis.

Earlier that day, while preparing breakfast, a volunteer for the evacuees, Norma Lladones, 71, died on the spot as a mortar pierced through the wall of their house in Barangay Tetuan, a kilometer away from the war zone.

Sept 22: Aquino: War’s about to end

President Aquino leaves Zamboanga City, assuring the public that the standoff would end anytime that day.

Sept 23: But wait, there’s more

The standoff didn’t end Sunday. On Monday, military choppers keep on firing their machine guns the whole afternoon. That evening, residents of Barangays Talon-Talon and Tugbuan leave their homes to evacuate to a safe place.

Sept 24: The other battle zone

In the outskirts of Barangay Talon-Talon, members of the police Special Action Force (SAF) guard mangrove areas. According to them, the area is an escape route for MNLF rebels. Supported by the Navy at sea, a Bronco plane bombs the mangrove areas incessantly. The other day, in that same area, a SAF sniper killed an MNLF rebel fleeing with 2 hostages.

Sept 25: Day of photo-op

To show the public that the standoff indeed ended, classes in the safe zones resume. A flag raising ceremony is held at the Sta. Clara Central School attended by Cabinet members and military officers. In photos and videos, this day looks like a normal school day with huge attendance. In reality, only 16 students attend the school opening. The rest are plucked from the evacuation center for the photo-op.

At the Edwin Andrews airbase, 3 slain government security forces are given departure honors. They were all killed by sniper fire from the MNLF.

More than 30 MNLF members who were either captured or have surrendered are presented to media in the evening. Their big fish on this day is a commander and former politician, Enier Misuari, nephew of MNLF chair Nur Misuari.

I left for Manila the following day. Back home, I saw TV reports of flags being raised in a mangrove tree in Barangay Mariki and the KJK building inside Barangay Sta. Catalina.

I had to ask myself: is this simply a flag-raising battle?

The military battle has probably ended, but a difficult war has just begun: the rehabilitation of displaced civilians and the restoration of trust between Muslims and Christians who have tried — and most of the time succeeded —to peacefully co-exist in the peninsula.

–Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.