SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – We all know the iconic scene of the US Marines planting the flag on Iwo Jima. If not from history books then from watching House of Cards and countless other series and movies based in Washington, DC, many of which use the larger than life memorial – the figures are more than 30 feet high – for dramatic effect. On the base are the names of all the wars and battles the Marines fought, including one I aimed a lower resolution iPhone on in a 2015 visit: “Philippine Insurrection 1898-1902.”

That name denies how the US came to control the Philippines: not just buying it from Spain, but fighting Filipinos who had already all but defeated Spain.

In his latest book, historian Rey Ileto says for decades that’s how Filipinos learned to refer to what most of us now know as the Philippine-American War. If I read Ileto right, he believes that thanks to that distinction, several generations lost touch with many of our heroes and heroics. And while the spell has been broken, we are still in many ways, in a phrase he uses, “mental colonies” of the US.

How has that influenced how we deal with the world, whether it is with direct rivals of the US, like China and Russia, or smaller countries somehow linked to these rivals? What have we lost due to this filter? How might President Rodrigo Duterte change that?

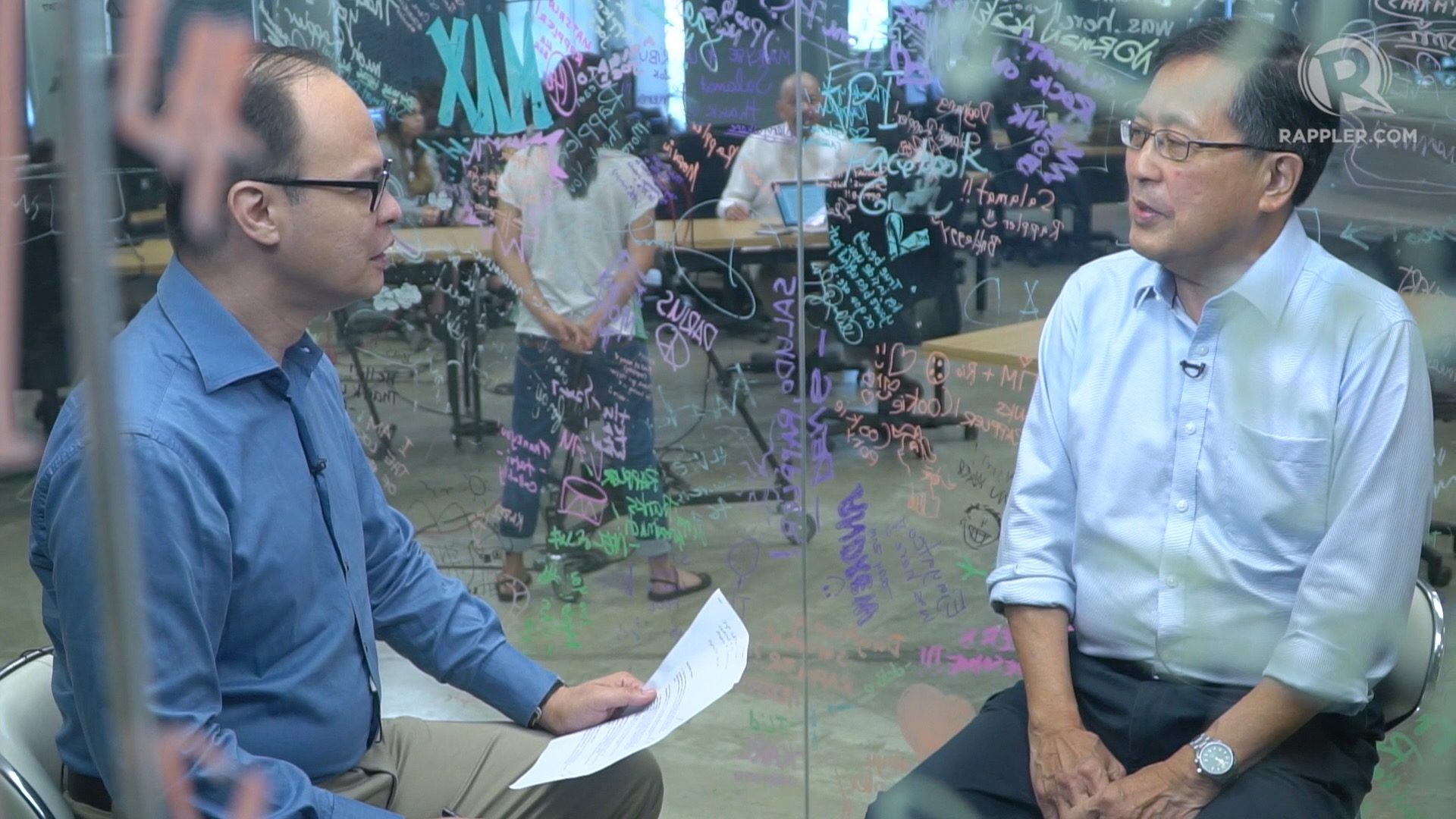

“I found it refreshing that the President is willing to open up to countries that were previously taboo to Philippine relations with. It’s a very positive move,” Ileto said when I interviewed him on Rappler’s “What’s The Big Idea?” series. “Very clever, but a bit dangerous.” (WATCH: What’s the big idea?: Rey Ileto: History and Duterte through un-Americanized eyes)

Ileto’s new book is Knowledge and Pacification: On the US Conquest and the Writing of Philippine History (Ateneo de Manila University Press). It follows his 1998 “Filipinos and Their Revolution” and the work he is best known for, his 1979 “Pasyon and Revolution.”

At 70, Ileto jokingly wonders whether there will be one more opus after the same 29-year stretch of time. Take a second to do the math.

In fact, Ileto says this book, in the works for more than 10 years, is finally out in large part after Rodrigo Duterte brought up the Philippine-American War – even displayed pictures of American atrocities – to brush aside questions about his war on drugs.

I got a better understanding of the war thanks to a chapter where Ileto talks about the skills, successes, backgrounds and character of men who don’t get mentioned as much as the flawed, fractious Aguinaldos and Bonifacios. Men like Miguel Malvar – who was de facto leader from Aguinaldo’s capture to his own surrender – and lieutenants like Norberto Mayo and Ladislao Masangcay.

It is one thing to be sad and angry at what the US managed to snatch from us thanks in part to factionalism – and even collaboration – at the top. It is quite another to find better men to feed one’s historical pride and nationalism. I only wish Ileto spent more time on them.

Ileto gets into how the more critical look at our relationship with the US had roots in the Japanese occupation, when our temporary masters’ natural desire to put the US in a bad light coincided with President Jose P. Laurel’s nationalist streak – the same Laurel who founded the Lyceum university where Ileto points out Duterte got his political science degree and initiation into anti-American activism. (Ileto also says Japanese-sponsored anti-American research probably allowed Teodoro Agoncillo to whip up Revolt of the Masses by 1947.)

There is also a revealing, personal chapter on Ileto and his father, General Rafael Ileto: West Point graduate, Army chief and vice chief of staff early in the Marcos years. The General Ileto chapter is a great transition from the war in the first part of the book to the later discussion of leadership and sometimes (for want of a better word) authoritarianism of General Ileto’s boss – the dictator Ferdinand Marcos – and the “boss mayors” who ruled under Spanish, US and Philippine law.

If I understand him right, Ileto says some scholars have focused on a few controversial local leaders to show that Filipinos don’t know how to govern, at least not in the idealized American way. And thus we should be thankful for the American tutelage. But there are reasons for the “bossism,” including the military backgrounds of some of these men. And many were not authoritarian at all.

Even when we spoke in June, Ileto said it was too early to label Duterte authoritarian.

“We are seeing him through other lenses instead of taking him on his own terms and trying to understand where he is coming from and what he is trying to tell us about how someone with experience of being mayor for 23 years,” Ileto says in the interview. “Of course there are negative as well as positive aspects to this but we we must learn to listen to understand what is going on.”

Duterte was new to the presidency when Ileto submitted his manuscript, which ends with the hope that this presidency marks a turning point in how we view the US and, by extension, ourselves. – Rappler.com

Coco Alcuaz is a former Bloomberg News bureau chief and ANC business news head and anchor. He now hosts Rappler’s “What’s The Big Idea?” interview series. Connect with him on Twitter at @cocoalcuaz

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.