SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – The Philippine National Police (PNP) has vowed to go after private armed groups (PAGs) ahead of the 2013 elections, and says there will be no sacred cows in this campaign.

“Lahat ng private armed groups di natin sasantuhin, whether they are related to any organization, any party or any individual,” Task Force Safe commander Deputy Director General Alan Purisima said in an All Soul’s Day statement.

Fine words. Except for two things:

- The police seems to make this vow every election season, yet there remain PAGs or private armies across the country.

- Authorities cannot even agree on the number of private armed groups they are supposed to crack down on.

For instance, maps obtained by Rappler showing the PAGs being monitored by the police indicate that there are 86 of them existing in 30 provinces.

The maps, which were dated September 15, 2011 and January 31, 2012 included the location of the armed group under surveillance, the names, designations and positions of the leaders of the armed group, as well as their political party affiliations.

Only one non-politician was listed by the police as a leader of a private armed group:

| LEADERS OF PRIVATE ARMED GROUPS | |

| Mayor | 43 |

| Congressman | 6 |

| Governor | 6 |

| Barangay Captain | 5 |

| Vice mayor | 2 |

| Vice governor | 1 |

| Councilor | 1 |

| Police | 1 |

| Unspecified posts | 20 |

| TOTAL | 86 |

The numbers were based on the PNP’s definition of terms. It says private armies are organized groups of two or more persons, legally or illegally armed, who use their weapons to intimidate for political or economic purposes.

“Private armed groups” therefore are not necessarily classified as “armies.” Retired General Edilberto Adan told this writer in a 2011 interview: “[In effect] they only become private armies when used by their patrons to terrorize by their patrons.”

These private armed groups often become dormant or inactive when the need for the group to exist is no longer there.

Adan was a member of the Zeñarosa Commission, which was formed soon after the Ampatuan massacre of November 23, 2009. Its mandate was to study the nature of the private armed groups and to recommend policies to prevent their proliferation.

Inconsistent count

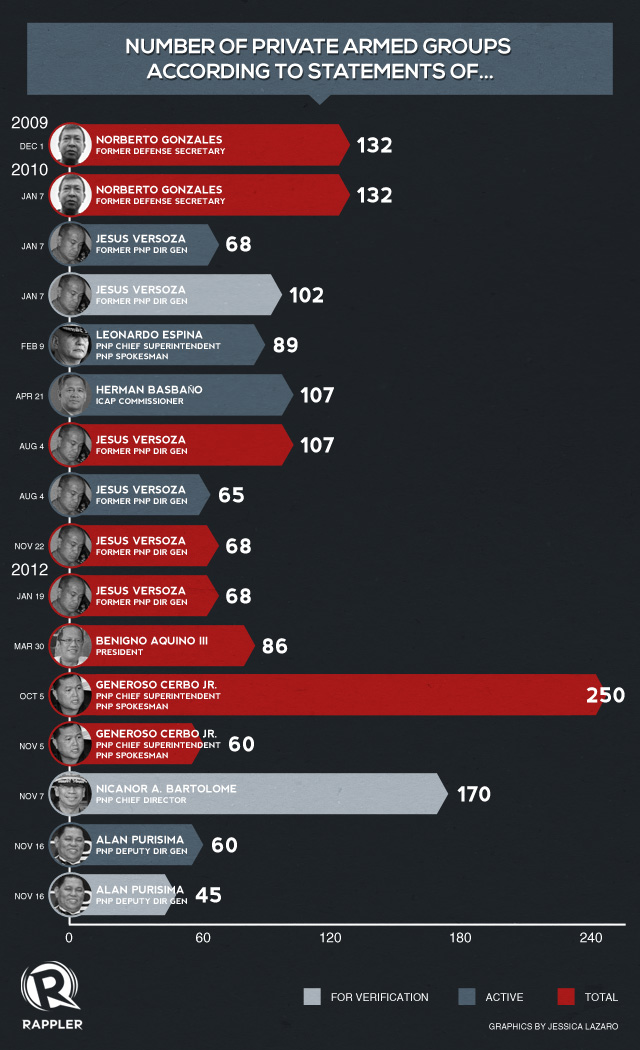

By October this year, the number of alleged private armies had increased to nearly 250. PNP spokesman Chief Superintendent Generoso Cerbo said these are working for politicians in various parts of the country and can have a major impact on the outcome of the national and local elections in May next year.

Days later, however, Cerbo gave a sigificantly lower figure. He said the PNP’s Directorate for Intelligence gave him a working number of 60, with 9 allegedly based in the ARMM.

Since 2009, in fact, official numbers of private armies cited by various authorities in their public pronouncements have vacillated significantly.

On January 7, 2010, months after the Maguindanao massacre, then Defense Secretary Norberto Gonzales said there were at least 132 private armed groups in the country.

That same day, Director General Jesus Verzosa, chief of the PNP, said there were 68 confirmed private armed groups. Of this number, 25 were in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), while 43 were found outside the region.

Verzosa said at the time that they were still “verifying” 102 other private groups suspected of possessing firearms—77 of them in the ARMM, and 25 in other regions.

Defining the problem

Part of the problem involves semantics, those who have studied the issue explain.

In its report, the Zeñarosa Commission noted that there is no law that specifically bans the maintenance of private armed groups. One of the key recommendations in fact is to enact a law to this effect.

It is difficult to crack down on private armies in the Philippines, Adan said, because more often than not they are not really armies in the sense that they have barracks or regular quarters.

“They are not static. They are not always with a patron,” he explained. “They are not in uniforms. Some of them are legally armed.”

Sometimes, Adan said, these armed groups are formed for a particular mission. For instance, members of one private armed group in Masbate were imported from other areas of Bicol for 2010 elections.

Some of them are contractual employees or legally employed by local governments as civilian volunteers.

Force Multipliers

The definition gets more complicated because the Philippine military, the police, with the support of various executive issuances, also routinely encourage the formation of militia groups—such as the Civilian Volunteer Organizations (CVOs), Citizens Armed Forces Geographical Units (CAFGUs), and even vigilante groups—in conflict-afflicted areas.

The military considers them as “force multipliers,” said Jennifer Santiago Oreta, a former member of the Commission Secretariat.

In many cases, though, they perform the role of armed guards of dominant local political personalities. “Politicians often register their bodyguards as civilian volunteers, thus legitimizing them,” Oreta said.

This gray area between private armed groups and government recognized “force multipliers” makes it possible for dominant political clans to accumulate firepower.

It is precisely what happened to the Ampatuans of Maguindanao.

On the lookout for allies in the fight against rebel forces in the area, the 6th Infantry Division, whose jurisdiction covers most of Maguindanao, cultivated an alliance with Ampatuan by supporting and arming his vigilantes.

Much of the clan’s firepower, according to sources, came from the military. Concerned military insiders had cautioned against the practice to no avail—until that fateful November day.

After the massacre, the military turned against its long time ally and claimed that members of the powerful Ampatuan clan, who were accused of perpetuating the massacre, had as many as 3,000 armed men under their control.

PNoy yet to revoke GMA’s order

This situation was enabled by Executive Order 546, issued by President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, which allows local officials to deploy CAFGUs and CVOs as auxiliary bodies for the Armed Forces of the Philippines to fight insurgents.

This executive issuance is still in effect today, making one wonder just how serious the administration is in going after these private armed groups.

In a text message sent to this writer on November 22, Adan said, “I believe some of the measures we recommended are being done. But much more needs to be done.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.