SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

On April 13, Rappler hosted the Rappler Senatorial Debate, bringing together 6 senatorial candidates exactly a month before the 2013 midterm elections. The focus of the following essay is on the event’s debate segment, where pairs of candidates were allowed to ask each other two questions. Rappler’s multimedia reporter and documentary producer Patricia Evangelista is an international public speaking champion and a former debater for the University of the Philippines, Diliman.

The crowds gather early. Gordon supporters in uniform red T-shirts fill the front rows. A woman with a notepad counts heads, “72, we’re at 72.” A man sets up drums. Any mention of Gordon over the loudspeaker prompts a screaming frenzy, in between bites of hotdogs and handfuls of Kirei chips.

Richard Gordon says the problem with the Filipino is that they do not think. They need to be led, and he hopes this time they will choose right. He would like to remind you he did not inherit his name from his mother, or his father. He earned it on his own.

Bam Aquino would like you to know he is the youngest candidate running under the administration coalition. He would also like to remind you how well the Philippines is doing today under the hands of President Benigno Aquino III, and that he would like to continue the Aquino promise. He also says he is repeatedly asked if he is the President’s son. He grins, self-effacing, no, he says, he is a cousin.

Risa Hontiveros admits it is difficult to run without a popular name, but says she has faith in the capacity of the ordinary people to create a senate for the good of all, as does Teddy Casiño, who suspects that people think of Casiño rubbing alcohol first before they think of Teddy Casiño.

Grace Poe says her name often, although perhaps not as much as her father’s name. Her people wear white vests over their yellow shirts, with her name printed front and back. Grace Poe, the “Poe” in capital letters. Grace Poe, printed on the back of the white vest. Grace Poe, “daughter of FPJ,” in bright letters on blue. On the off chance you forget, she will say it again. Poe, Grace Poe.

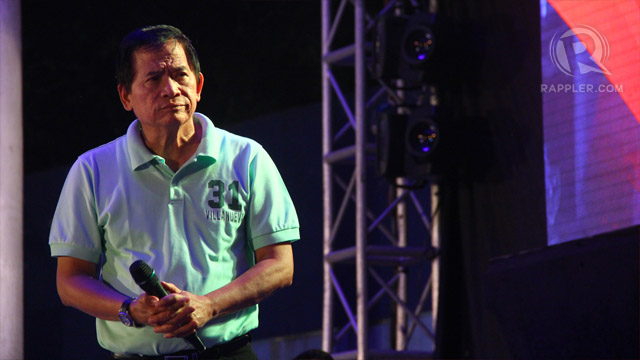

And Brother Eddie Villanueva, speaking in the third person, would like you to know that Brother Eddie is an activist, that Brother Eddie was jailed twice during martial law and that Brother Eddie was willing to be jailed in defense of truth and democracy. Brother Eddie says that Brother Eddie became an intellectual communist. Brother Eddie says he was a student leader and a shoe salesman and a clerk in a bookstore before Brother Eddie became an evangelist. Brother Eddie says, finally, to remember that Brother Eddie has no personal agenda, that Brother Eddie’s agenda remains God and for country. Vote for Brother Eddie, says Brother Eddie, because Brother Eddie will become your salvation.

Casiño vs Hontiveros

It was the faceoff between former Akbayan Rep Risa Hontiveros and Bayan Muna Rep Teddy Casiño that promised actual debate.

Aside from a complex history stemming from historical differences among socialist ideologues and open tension between rival left-wing organizations and their allies (Read: It’s war: Akbayan vs Anakbayan) the two camps have been running largely similar campaigns, banking on the minority status of their constitutuents.

Both claim to represent the needs of “the ordinary person,” proclaiming themselves voices of the underdog. Both camps argue an insider’s view of poverty, oppression, labor, activism and human rights. The debate last Saturday would be one of the first times Casiño and Hontiveros would face each other on a national platform, outside of almost-rabid warfare on online forums and vicious press releases sent out in response to each other’s public statements. The debate was an opportunity to cut through the overlapping stances both sides have been taking, one Hontiveros immediately took advantage of hitting Casiño with his record as a human rights defender.

“You project yourself as a defender of human rights,” Hontiveros told Casiño. “Why was it that in your 9 years in the House of Representatives, I recall that you did not, even once, speak when it came to abuses of the New People’s Army against ordinary citizens?”

It was an important question, highlighting Bayan Muna’s reluctance to come to the defense of civilians who were killed and injured in recent encounters in Misamis Oriental and Negros Occidental. (Read: NPA apologizes for Negros ambush).

Casiño drops the ball here. Instead of denying Hontiveros’ accusation, Casiño concedes, justifying his selective defense by the fact there are more “ordinary people” victimized by the military.

Although Casiño gives the standard rhetoric in his press releases—“If there are any proven violations [by the CPP-NPA-NDF], I hold them accountable and demand proper corrective action from them”—he speaks as if the capacity to simply condemn human rights violations is a currency in limited supply. The New People’s Army, argues Casiño, has its own systems for justice, and is accountable to the victims. He adds that they hold the NPA accountable to their “own systems” where they decide “how to change themselves” and “correct their mistakes.”

“Our experience with rebel groups is that when you face them with complaints against them, they will admit to them immediately. Once they do, they will find ways to give justice to the victims. It doesn’t become a very big issue.”

What Casiño forgets first is that he is now campaigning for a position in a government whose laws are not the laws espoused by communist rebels, and that a lawmaker claiming to be a human rights advocate can never claim he is satisfied by justice meted out by any institution outside of the courts of law.

What he forgets second is that the people who are begging for assistance in bringing justice to victims murdered by the NPA are also “ordinary people.” (Watch: Casiño: A Rappler Profile). It is an odd answer for a man who claims to be the voice of all victims. His answer in the debate draws the line Hontiveros emphasized with her question—when it comes to human rights violations, Casiño will stand in defense of some, not all.

It does not mean that Hontiveros showed particularly well against Casiño, perhaps also granted his failure to take advantage of the stage to demand answers of Hontiveros and Akbayan.

He could, for example, have asked about the implications of Hontiveros’ frequently denied relationship with presidential political adviser Ronald Llamas (Read: Politicians and their lovers). He could have asked her to differentiate her party from President Aquino’s liberals, or demanded, for example, exactly why Akbayan deserved to be called a minority while part of the President’s coalition. Instead, he asks whether Hontiveros would support the removal of customs chiefs Ruffy Biazon, a question that Hontiveros does not answer, instead offering a rambling commentary on the government’s commitment to reform, Biazon’s discussions with the President, the dangers of privatization, the need for tighter borders and the behemoth that is customs smuggling.

It appears Hontiveros was better prepared and more aggressive, Casiño wasting questions and failing to point out the flaws in her reasoning. Hontiveros manages to claim ownership of the Reproductive Health Bill and the Freedom of Information Bill, pointing to Bayan Muna’s shifting support, while Casiño points to Hontiveros’ 2010 acceptance of campaign funding from the Aquino family.

“How,” asks Casiño, “do you propose to stay independent and remain a check and balance to the ruling party and traditional politicians?” Both answer well, Casiño blaming his flip-flopping on Malacañang, Hontiveros enumerating the varying positions she took against the administration. The truths behind either answer are a matter of perspective, but neither called the other out. It was not the best of debates, but it was a debate, a far cry from the congenial back-patting that occurred when Grace Poe and Eddie Villanueva next took the floor.

Poe vs Villanueva

Grace Poe begins with a smile and a gift for the preacher in green. “I would like to ask what projects or outreach programs you’ve supported in your group. For example, for the youth or whatever else your group has done.”

It is a free ticket to campaign, and Villanueva took full advantage, enumerating at high speed every Jesus is Lord ministry, going from jails to hospitals to the jobless to the 11 million OFWs in 52 countries including “most of Asia, China, Pakistan and Afghanistan,” going so fast and so far that Brother Eddie Villanuva finally forgot to speak in the third person.

And yet all the assistance Villanueva claimed to have provided his religious constituents matters very little in the context of a senatorial election.

Had Poe considered this a debate, or had at least believed Villanueva a worthy candidate, she could have asked questions that respected the fact Villanueva is a candidate for the highest legislative position in the land. Even after the question, Poe was in a position to encourage rational discourse, to use her second question to ask if Villanueva intends to prioritize Jesus is Lord chapters in disbursing his pork barrel, to ask, for example, if he would allow his religious affiliations to play a role in the creation of laws or even what role he believes religion should play in the national agenda.

Instead she smiled at the evangelist, said she had no other questions, and effectively reduced the debate round into a Jesus is Lord proclamation rally. Perhaps there is no malice here, perhaps this is testament to how Grace Poe intends to play the legislative game—I scratch your back and you scratch yours—at the expense of actual issues. (Read: The independence of Grace Poe).

It was a good ploy, at least in terms of Villanueva, who was happy to use his questions to promote the mythology of Brother Eddie Villanueva.

When your father was alive, says the preacher, he came to my home to ask me to join him in rallies. Would you join us in protest if ever the administration promotes policies and programs that harm the people and benefit only the rich?

Yes, says Grace, for as long as the protests “damage no one.”

When I was an activist at the UP College of law, says Brother Eddie Villanueva, I had jailed two policemen who killed a peasant in Bocaue. I had jailed a judge, a fiscal, four lawyers and a drug syndicate in Bocaue. If we are elected, would you join me, he asks, to have jailed those who have become too abusive of the people?

Of course, says Grace, that should be done.

This was not a debate, so much as a script built for apparent coalition partners. Villanueva’s repeated reminders to the public of his influence—FPJ would visit me—and his emphasis on his activist role—I jail bad men—appeared more important than his actual questions, questions that only a certified idiot could answer badly. Of course Grace will stand up against abusers. Of course Grace will want to jail criminals. Of course, Brother Eddie, thank you for that Brother Eddie, you are right Brother Eddie.

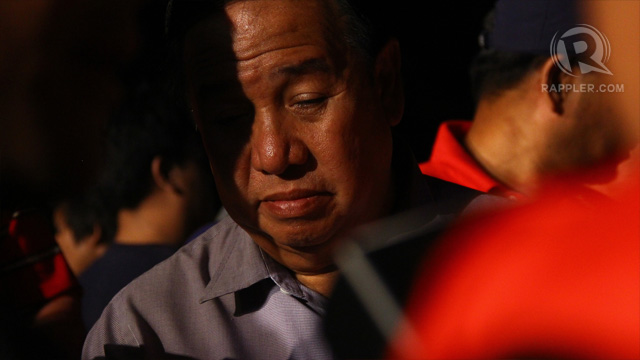

Aquino vs Gordon

The last pair, Liberal Party vs the United Nationalist Alliance, pits Bam Aquino—“I am a son of People Power”—against Richard Gordon. Aquino carried himself well, his apparent humility and seeming decency only emphasized by the roughshod manner Gordon employed in demonstrating his intellectual and administrative superiority over Aquino and the rest of the nation.

Aquino emphasized his youth, calling Gordon a senior senator with both his questions, asking Gordon what role he felt young officials should play in government, and what issues he felt both he and Aquino could collaborate on.

Gordon chose not to answer, and instead waxed poetic over the need for wisdom and maturity in the Senate, and managed to insult, in the span of 4 minutes, the Filipino youth, the elected senators—“Sometimes they’re not willing to debate. Sometimes they do nothing because they do not have the capacity to debate”—and the voting public. There seemed to be a large amount of contempt for both the members of the Senate and the public that voted for them, and Gordon made no attempt to mask that contempt even earlier in the debate—“The problem is that people do not think.” It was a ploy that failed when Gordon ran for the presidency, but it may very well work for the Senate. The strongman cometh, and this strongman reads Camus.

“That is the story of our country. Nothing is happening because all we get are promises and all we get thrown are free T-shirts. Shouldn’t it be that we teach our people to have jobs so that they can buy their own T-shirts?”

It is a fair idea, an important one, and yet it makes it necessary to wonder who paid for the 72 T-shirts printed with Gordon’s name worn by the 72 people screaming his name in the audience.

Gordon correctly attacked Aquino’s LP links, throwing Aquino a shopping list of national failings, ranging from smuggling to extrajudicial killings to the lack of electricity in Mindanao. Aquino answered well, emphasizing improvements under Aquino’s term, adding that changes do not come overnight and that continued development needs to be led by the Liberal Party.

It was the second follow-up question where Aquino floundered. Gordon asked again about extrajudicial killings in Davao Oriental and Metro Manila, Aquino answered again the same way—the economy, gradual change, LP at the helm, without acknowledging the brutal reality of more deaths outside the law.

“I don’t want to sound like an apologist for the President,” says the President’s cousin.

It was an important defense, but one that only emphasized what was lacking—a defense.

Welcome to the party

It was, in all, an important debate, revealing not so much platform and policy but the manner political maneuvering has influenced the ability of the political elite to engage in debate. Even knowing the rules of debate may shift from one floor to another, the basics are sorely missing.

Some would argue that this is a campaign, not a debate, that there are values more important than the ability to ask the right question or articulate the right answers.

But there is a reason logic and reason are important, and this is what seems to have been forgotten. Senators are required to debate, to have the courage to clash and question and demand, to impose reason over rhetoric in an attempt to craft the best possible laws in the service of the people.

Debate tests not only arguments, they test people, a test that the Senate failed collectively with the passing of the Cybercrime law.

The Senate is not meant to be a motley collection of national favorites, they are meant to be the best of the nation, statesmen in the grand tradition, because what is at stake is not a seat number, it is the public they claim to represent, ordinary or otherwise.

The crowd walks off at the end of the debate. Those carrying banners head off early, some say they have already been paid. The drums are hauled into trucks, the whistles are turned in, vests are folded carefully for the next sortie. Barefoot children scramble for the leftovers. Perhaps the preacher should pray for their souls.

Watch the full #RapplerDebate:

– Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.