SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

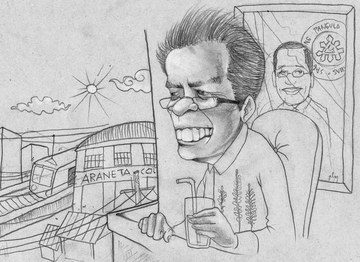

Illustrations by Geloy Concepcion Design by ANALETTE ABESAMIS and DOMINIC TUAZON

Rappler’s series of

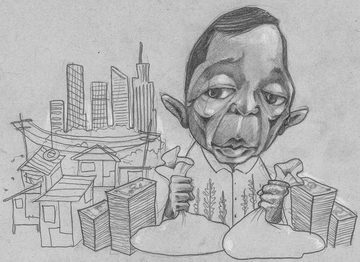

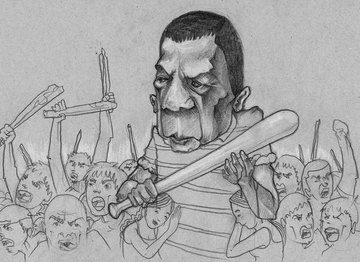

Here, in The Demonized, the second installment, we examine the worst versions of candidates running for President, as imagined by their critics. These profiles condense the range of commentary from political opponents, interest groups, columnists, as well as the grievances that populate both online and offline conversation. We hope to make sense of what frightens, what offends, and what angers a nation in search of a leader.

The story begins, as most epics do, with the birth of a foundling. Nobody knew where she came from, only that she was left, one morning in September, on the steps of the Parish Church of Jaro. She could have been one of many orphans left to scrabble for charity and make their own way. But this one child, by virtue of fate or circumstance or God’s kindly eye, was adopted by the best of parents to live the best of lives, surrounded by comfort and love and all things good and true.

In the grand epic that has become the public narrative of Grace Poe’s life, she is a special creature, the unknown hero chosen from unknown roots, her heart pure, her courage vast.

Listen, she says, I was once as small as you. See me now, and see what I have become.

What Grace Poe has become is a story, reduced to plot lines that say very little about the woman whose claim to greatness doesn’t quite match the lightness of her experience. Watch her, amazing Grace, the brave messiah in pearls, delicately weeping into a white square, making a plea for the throne while claiming the divine right of kings.

The king’s daughter returns, and she comes for his sword.

The American President

In 2001, Grace Poe raised her right hand and swore an oath before the flag of the United States of America. She promised to support and defend her country’s laws and Constitution. She promised to bear arms when called upon to serve. She promised that her oath was given freely, without reservation or evasion.

She promised, most of all, to “absolutely and entirely renounce and abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty” – in her case, the foreign and sovereign Republic of the Philippines.

That renunciation, she says now, was only a matter of necessity.

“That was the situation of many of our countrymen today,” she said. “I think that my situation has actually brought into our consciousness the situation of many of our countrymen now. How the state failed us with opportunities that we could have provided our families with dignity staying here.”

Except that the state did not fail Grace Poe. She was a 22-year-old newlywed who wanted to be independent of her millionaire parents. Her choice wasn’t necessity, at least necessity as defined by most of the roughly 2.3 million Filipinos working overseas. Her sacrifice included a house in the Washington suburbs, driving her children to school, and the experience of cleaning her own house – an experience she believes grants her membership into the sisterhood of thousands scrubbing foreign toilets.

“Madame Senator, you are not an OFW,” Vice President Jejomar Binay called her out in a televised debate. “I’m not saying I am,” she responded, “but I’m saying I’ve lived in another country.”

This is the story as imagined by her critics. One day, Grace Poe, the coddled child of film celebrities, whose background and education allowed her every opportunity to serve in comfort in the Philippines, traded the citizenship she now vehemently claims in exchange for a green card and the pursuit of love. Here stands the woman with the moral cause and the moral soul, waving from the stage, smiling at her people, the self-proclaimed savior of the millions who suffered in the republic she abjured.

On-the-job training

Grace Poe’s political career began with a promise to continue the legacy left behind by her father, action star Fernando Poe Jr. Her campaign poster was a family portrait. Her speeches began and ended with his name.

“She seemed to claim that her bid for the

Unless and until she decides to slip on leather gauntlets and star in a Carlo Caparas television sequel, her claim of fulfilling a family legacy holds no water.

“The presidency is not on-the-job training,” said Liberal Party standard-bearer Mar Roxas. “The future, the lives, and the well-being of a hundred million Filipinos are at stake.”

Poe answers criticism by claiming she offers a fresh perspective. Yet a review of both her legislative record and her time running the film and television review board offers no hint of a breathtakingly novel approach to government work. The laws she championed – free lunches for schoolchildren, for example – may address child hunger, but are in no way revolutionary. Even her campaign to pass the freedom of information bill, arguably her best known crusade, has long been fought for by legislators in both Congress and the Senate.

Her press releases say that “her committees have been among the most active in conducting public hearings and meetings in aid of legislation,” a claim that will inevitably be true for the committee on public order, regardless of who heads it.

Certainly Grace Poe did her job, no more and no less, but 3 years of minimal missteps – and a single bill passed – may be no resumé for the president of the republic.

“It would be risky,” said United Nationalist Alliance standard-bearer Binay, to entrust the Philippines to leaders “without experience and competence.”

In 2015, Poe offered a 20-point agenda for her presidency. She promised to eliminate classroom backlogs. She promised free irrigation. She promised to increase the infrastructure budget. She promised to hold the corrupt accountable. She promised the minimum wage. She offered to lower electricity costs. She committed to pursue peace. She pledged to protect the rights of persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples, urban poor, women, youth and children, the LGBT sector, and senior citizens. She promised each community “a proper hospital, staffed with enough doctors, nurses, and midwives, and with all the necessary equipment and supplies.” She swore she would fight for the West Philippine Sea through peaceful means. She will end heavy traffic, build more roads and bridges, offer faster Internet, protect artists, support athletes – “We should never give up on our dream to win an Olympic gold medal” – strengthen tourism, focus on disaster risk reduction, and, of course, offer free lunches to school children.

The items on her platform have long been part of the agenda of nearly every candidate. None of these ideas are fresh. None of them will transform the landscape of Philippine public policy.

“There’s promise after promise, but where are we getting all that money to fund all those projects? That is the question,” asked presidential candidate Miriam Defensor Santiago in the Cagayan de Oro debate.

Everyone’s hero

All of this reveal the hollow core of the Poe campaign. Claiming all is a priority means nothing is. By standing for everything, she stands for nothing. Here is a woman so desperate for approval that her presidency runs the risk of belonging to everyone other than herself – including the man she chose for her vice president.

Grace Poe is “open” to the death penalty, “but will call for a national plebiscite.” She is “open” to the burial of dictator at the heroes’ cemetery, but hedges by saying there should be a legal review. At a time when the reproductive health bill had earned the support of every women’s rights advocate, she said “the debate should be made public” – even when it was.

In 2013, she was a guest candidate of the Liberal Party as well as the opposing United National Alliance. She said she saw no wrong in straddling both – if it can help her candidacy, why not?

“Here in our country,” she said, “it has hardly any value when it comes to having a political party because people change parties like they would depending on the political weather, right?”

Mother bountiful

“People ask me what I have that other candidates don’t,” she said after the High Court announced she is qualified to run. “This is what I can say: as a woman, as a mother, I have common sense and compassion for our fellow men.”

Grace Poe is not the only woman among the presidential candidates, and not the only mother. That place is also held by Santiago, senator and judge, whose own extensive curriculum vitae trumps not only Poe’s but arguably every candidate for the presidency. Even without arguing against Poe’s own narrow view of what a woman should be – “There’s really a specific role of the father, he’s the tough guy in the family, but the woman is more into the caring side” – her faith in motherhood’s magical properties is negated by her own father’s much-vaunted tender-hearted benevolence.

But the larger criticism against Poe’s claim to greatness is that she holds no monopoly on the virtues she has claimed, not as a candidate, not as a woman, certainly not as a mother. Of the 54 million Filipinos voting, more than half are females, a large part are mothers, and many more have suffered and continue to suffer beyond the experience of one Grace Poe. What then does Grace Poe have that the average, commonsensical, compassionate Filipino mother does not? What makes her so special that she can claim that her mistakes are no reflection of her skills?

Her posters plead for the public to “Adopt Grace.” It is a slogan that belongs more to humanitarian pamphlets and Facebook fund drives.

Here is what it means – the child in distress will rule the nation in turmoil.

“I was not simply adopted – I was a foundling,” said Poe, who wept during her speech. “Even if I didn’t feel less of a child of my parents, society sometimes made me feel so.”

Poe’s self-constructed narrative of persecution places drama as cornerstone of her campaign, claiming that just like everyone else, just like those who are ill, poor and forced to work overseas under precarious conditions, Grace Poe, too, draws from her dramatic life story.

(Read: FULL TEXT: Grace Poe: Ipaglalaban ko ang mga may hugot)

This is a woman claiming to be qualified for the position of commander-in-chief, all while painting herself the vulnerable foundling in need of care and affection. Her campaign is anchored on drama – a presidency whose single platform is biography. Strip her of the story, take away the violins, and all that will be left is a woman who once abandoned the same country she is asking to lead. Remember the orphan. Imagine the small child. Vote with your heart. Adopt Grace Poe.

Listen to her now, and ask her who she is. Father’s daughter, mother’s child, barely a citizen, not quite a hero, a neophyte senator whose one great distinction comes from collecting on the kindness of strangers. See her, amazing Grace, the brave messiah in pearls, delicately weeping into a white square, making a plea for the throne. Her virtue is not compassion so much as it is pity.

The king’s daughter returns, and she comes carrying a tin sword. – Rappler.com

Editor’s Note: All quotations have been translated into English. This is The Demonized, the second installment of The Imagined President series, where Rappler examines the negative images of candidates running for President as imagined by their critics. We hope to make sense of what frightens, what offends, and what angers a nation in search of a leader. For Part 1, The Idealized version of Senator Grace Poe”s profile, read The Once and Future King.

Patricia Evangelista is Rappler’s multimedia manager. She is an international fellow of the Dart Center Ochberg Fellowship for Trauma Reporting and was awarded the Kate Webb Prize for exceptional journalism in dangerous conditions. In 2016, she received The Outstanding Young Men award for the field of journalism. Tweet her @patevangelista.

Nicole Curato is a sociologist from the University of the Philippines. She is currently a Discovery Early Career Research Award Fellow at the Center for Deliberative Democracy & Global Governance based in Canberra. In 2013, she received The Outstanding Young Men award for the field of sociology. Tweet her @NicoleCurato.

Checking your Rappler+ subscription...

Upgrade to Rappler+ for exclusive content and unlimited access.

Why is it important to subscribe? Learn more

You are subscribed to Rappler+

Join Rappler+ Donate Donate UPGRADE TO RAPPLER+ TO COMMENT JOIN RAPPLER+ TO COMMENT

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.