SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – In the Philippines, the national government has its hands full — not with implementing tobacco regulation but with court cases meant to stop its efforts.

In 2005, the country was supposed to begin enforcing tougher tobacco control policies to comply with an international treaty it signed, the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). The 2008 deadline for instituting more effective packaging breezed by. As did the 2010 deadline for comprehensively banning tobacco promotions and sponsorships.

With its hands tied in legal battles, the government has largely had to settle for weaker measures, such as text warnings instead of the recommend picture-based ones.

In all cases in the courts to date, the tobacco business has had the upper hand. Tobacco firms are mostly challenging proposed government oversights, specifically:

- Compelling companies to place picture warnings on cigarette packs. Less than two months after the Department of Health issued Administrative Order No. 2010-0013 calling for graphic health warnings, 5 major firms challenged the mandate. So far two tobacco companies have been victorious in getting regional trial courts to declare the order invalid while the other firms have obtained favorable preliminary rulings.

- Banning smoking in select public places in Metro Manila. Last July, the Metro Manila Development Authority (MMDA) began arresting people caught smoking in certain open areas of the metropolis, like transportation terminals and gas stations, in an attempt to limit exposure to secondhand smoke. A local Mandaluyong court swiftly sided with apprehended smokers, issuing a preliminary injunction in October to stop the agency from making more arrests.

- Giving the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authority over tobacco products for the first time. In 2011, the Philippine Tobacco Institute, an association of leading tobacco companies, asked a Regional Trial Court in Las Pinas City to set aside the implementing rules and regulations of the FDA Act of 2009 which spelled out that regulation of tobacco products falls under the purview of the FDA. Despite what seemed like an initial victory for the FDA in the preliminary rulings, the regional court ultimately sided with the tobacco institute, stripping the FDA of the authority to supervise the quality of tobacco products on behalf of consumers. The FDA elevated the case to the Supreme Court but it has not sought a restraining order or attempted to check tobacco as it waits for the decision.

- Limiting ads for tobacco products to the interior walls of stores selling them. In 2008, a Marikina court sided with a broad definition of point-of-sale that allows tobacco companies to place advertisements on the outward facing area of a store and within the perimeter of the establishment. The ruling lets tobacco companies turn the shop itself and the space on which it stands it into an advertising area, offering a way around the country’s seemingly strict law prohibiting outdoor billboards.

- Blocking and regulating tobacco promotions. The Department of Health’s (DOH) attempt to reign in industry marketing practices was blocked by the Regional Court and the Court of Appeals. In the 2011 Court of Appeals decision, Associate Justice Noel Tijam wrote that the DOH “committed grave abuse of discretion,” by trying to ban tobacco promotions, reopening the door for creative marketing practices and sponsorships. The DOH has appealed the unfavorable decision, raising it to the Supreme Court.

“In all tobacco control cases in the Philippines there has been no victory for public health ever,” said Evita Ricafort, a lawyer with Health Justice Philippines, a non-governmental group that keeps tabs on all the cases filed by the tobacco industry and offers legal aid to the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG).

Cases meeting slow traffic

Over the past 5 years, 11 legal cases have cropped up involving the tobacco industry. Government and private individuals who have taken on the industry have not won a single one.

Lower courts earlier decided in favor of the tobacco firms in 8 of the cases, but government lawyers have appealed the decisions. The 3 other cases are pending in regional trial courts. At various stages, the cases have met agonizingly slow traffic.

With stronger regulations stalled, the Philippines has fallen behind regional peers in curbing tobacco use. In the Philippines, there are 87,600 tobacco-related deaths every year or 10 every hour, according to the DOH and the World Health Organization (WHO).

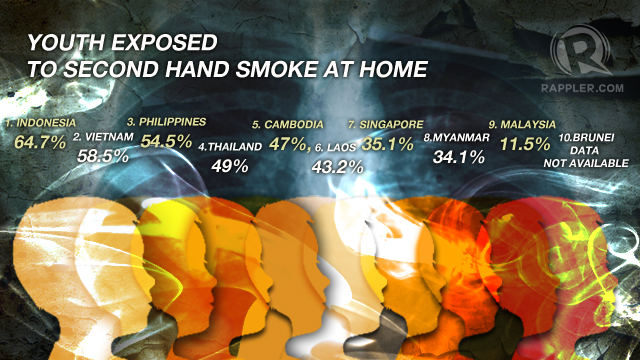

Perhaps it is no coincidence that the 3 countries in the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) with the highest per capita cigarette consumption—Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines—all do not have picture warnings on cigarettes.

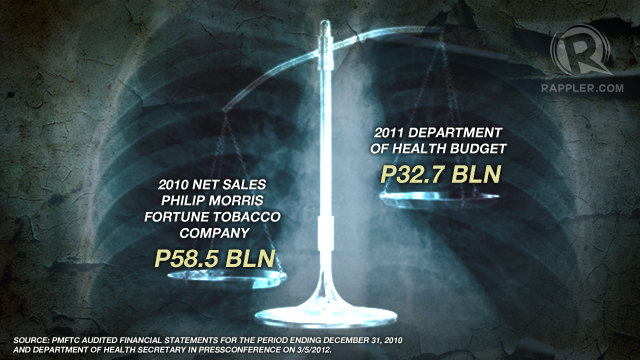

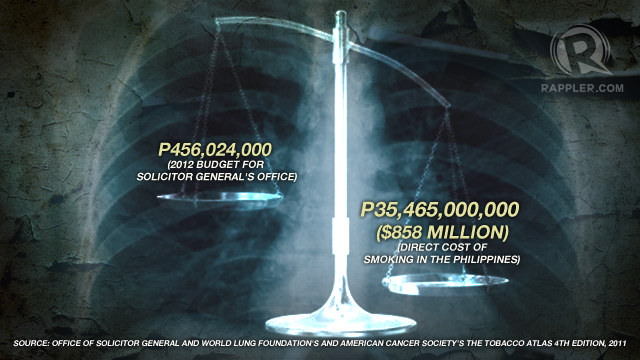

Big budgets

The victories of the tobacco firms are not surprising. They can afford the best law firms for their legal defense. Defending government, meanwhile, are underpaid lawyers with massive case loads.

Tobacco companies have been able to afford numerous lawsuits that defeat or delay control measures.

In May 2010 then Health Secretary Esperanza Cabral issued Administrative Order No. 2010-0013 mandating picture warnings that graphically show the ills of smoking. She also sought to ban misleading descriptors such as “mild” and “ultralight” on every cigarette pack sold in the Philippines.

But the AO was only a paper tiger, with not a single tobacco company complying.

In a clever legal strategy, the AO was opposed in 5 separate courts by 5 different tobacco firms: Fortune Tobacco, Mighty Corp., Philip Morris Fortune Tobacco Company (PMFTC), Japan Tobacco International (JTI), and Telengtan Brothers & Sons, which is doing business under the name and style La Suerte Cigar & Cigarette Factory.

The move of tobacco giant Philip Morris to oppose graphic health warnings before a regional trial court in Batangas is the height of irony. Batangas hosts the tobacco firm’s main Southeast Asian manufacturing plant, where cigarettes are packaged with the picture warnings for export to Thailand.

The government is now fighting for the AO against experienced and respected law firms. Tobacco companies have employed the likes of Romulo Mabanta Buenaventura Sayoc & de los Angeles, one of the oldest and largest Philippine law firms specializing in corporate cases.

Japan Tobacco International is being defended by Villaraza Cruz Marcelo & Angangco, which has experience fighting Petron Corporation’s legal battles. Meanwhile, the court documents for Mighty Corporation are being signed by retired Associate Justice of the Court of Appeals, Hector Hofileña.

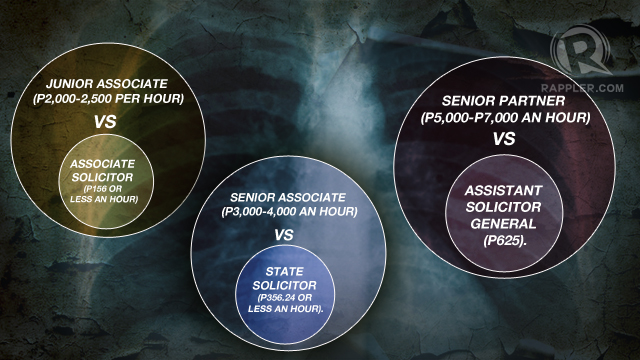

Industry sources say average hourly rates at a medium-sized firm are P2,000-2,500 an hour for junior associates. Compare that to the roughly P156 an hour (assuming a 40-hour work week) or P25,000 a month for an entry level attorney in the OSG. A senior associate in a medium-sized firm would average P3,000-P4,000, about 10 times what a state solicitor makes per hour.

The disparity may be even worse. While P57,000 is the average monthly salary for a state solicitors, they often work more than the expected 40 hours a week, bringing home work or even sleeping at the office.

The cases against JT International and Fortune Tobacco, for example, are only 2 of the roughly 2,500 cases that the likes of State Solicitor Joan V Ramos-Fabella is handling for the government. She has 25 times the caseload of a lawyer at a mid-level law firm, who by comparison might handle an average of 100 cases, according to industry sources.

Assistant Solicitor General Sarah Jane Fernandez is firm that despite being relatively over worked and underpaid, government lawyers are up to the task of fighting the larger firms.

She admits, however, that the number of case load that government counsels handle is a factor in their preparation to go to legal battle. “Perhaps they (opposing counsel) can focus more [with fewer cases].”

Who benefits from delays?

Alex Padilla, a former health undersecretary who spearheaded his department’s battle against tobacco, explained that the legal stalemates only help one party: the tobacco industry.

“Either they (the tobacco industry) water down provisions or delay legislation to death,” said Padilla. In either case, tobacco firms hold off the implementation of the contested tobacco control measures.

Padilla pointed out that it could be argued that the tobacco firms are engaged in forum shopping, which “is a prohibited practice in our courts.”

Forum shopping happens when cases of the same nature are filed with different courts, in the hope that if one case is lost, another will still get a favorable decision. So far, none of the courts have called the tobacco firms to task for this practice.

The tobacco firms have denied engaging in forum shopping, although it seems unlikely that the companies didn’t know about each other’s lawsuits.

As a former PMFTC employee said: “They’re all members of the Philippine Tobacco Institute (PTI). So as an industry I think they work closely together. There are regular meetings.”

Cigarette companies are known to work together within PTI when there are issues that affect the industry as a whole.

PMFTC is the joint venture of Fortune Tobacco and Philip Morris Philippine Manufacturing Inc. However PMFTC and Fortune have filed two separate cases challenging AO 2010-0013. Fortune lodged its case in Marikina City, where a neighborhood is named Barangay Fortune in its honor. PMFTC brought its case to Tanauan City, which is home to PMFTC’s state-of-the-art cigarette manufacturing plant.

PMFTC denied Rappler’s multiple requests for an interview.

Tanauan became the site of a major victory for tobacco when in February the court declared the A.O. invalid.

But it’s not just the government who is losing ground against tobacco firms.

Delays in court confront private individuals, like Father Robert Reyes, who is better known as the “running priest” for the runs he takes to support social causes.

His dead brother’s family is seeking damages from Philip Morris over what they claim were deceptive marketing practices directed at youth. He believes the company’s products killed his brother Vincent, who started smoking at 14, and died from a metastatic cancer that spread from his lungs to his bones and brain.

“It is the only existing damage suit filed against a tobacco company in the Philippines that we are aware of,” said Ricafort.

Filed in 2004, it took the Makati Regional Trial Court 5 years to calendar the case for hearing. And 3 years later, the case is still being heard.

PH lags behind Asian neighbors

In the face of legal setbacks and stalemates, the Philippines has fallen behind its regional economic peers in implementing tobacco warnings. Of the top 6 economies in the ASEAN, 4 currently use graphic health warnings.

The 2 that have failed to implement the warnings are the Philippines and Indonesia. Both countries have received a shameful Dirty Ashtray Award from the Framework Convention Alliance, a Geneva-based confederation of 350 organizations pushing for the implementation of the FCTC in the signatory countries.

Casting the net further among all the ASEAN countries, high and low income alike, 4 countries have enacted the warning (Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, and Brunei), while 6 have not (the Philippines, Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia, Myanmar and Laos).

The picture warnings were so effective in Singapore that after the initial implementation in 2004, a survey by the Health Promotion Board, an arm of the Ministry of Health, found that 28% of smokers reported smoking fewer cigarettes. The pictures stigmatized smoking to the point where 14% of smokers said they avoided smoking in front of children.

Currently 35% of Singaporean youth are exposed to secondhand smoke in the home, compared to 54.5% in the Philippines.

Joy Flavier-Alampay, regional communications manager of the Thailand-based Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance, says the Philippines has an inherent weakness in pushing for tobacco regulation. Her organization monitors the implementation of graphic health warning policies across the region.

She pointed out that in the Philippines, the Inter-Agency Committee on Tobacco, the body charged with regulating the companies, includes a representative of the tobacco industry.

“There are certain things that you cannot push, people will always put their interests on the table,” said Flavier-Alampay, who is also the daughter of former health secretary and two-term senator Juan Flavier.

Downward trend

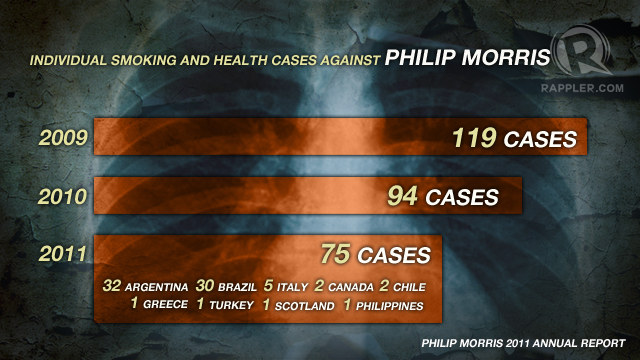

The industry is getting more aggressive in hauling governments to court—not just in the Philippines but in other countries with anti-tobacco policies. These days consumers are leveling fewer cases against tobacco firms.

Individual smoking and health cases against Philip Morris have declined in recent years. Of the cases Philip Morris documented in its 2011 Annual Report, 32 were in Argentina, 30 in Brazil, 5 in Italy, 2 in Canada, 2 in Chile, 1 in Greece, 1 in Turkey, 1 in Scotland, and 1 in the Philippines.

The court rulings, which favor tobacco companies, have effectively brought anti-tobacco efforts to a complete halt.

“No one’s moving forward, it’s sort of a chilling effect on the agencies. If there is a decision against you and you move forward with implementation, the court can cite you in contempt, fine and imprison you for disobeying an order. That has led to some agencies’ reluctance (to move forward),” said Ricafort.

One possible option is to implement graphic health warning in areas not covered by the current court cases, explained Dr. Eric Tayag, an Assistant Secretary of the Department of Health.

But the Health Department is not keen on that. “What’s the use? We want equity. We don’t want to choose cities where they will be. We want graphic warnings to be universal and not just limited to certain cities,” Tayag said.

Attorney Ricafort hasn’t stopped following up on the cases and offering legal support to the Solicitor General’s Office, yet even she admits, “We’re not even on square one, we’re on negative 100.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.