SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – It is one of the Philippines’ main weapons against illegal drugs yet Republic Act 9165 or the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002 looks good only on paper.

With President Rodrigo Duterte’s fight against drugs, this 14-year-old measure was suddenly put under the spotlight.

RA 9165 mandates the government to “pursue an intensive and unrelenting campaign against the trafficking and use of dangerous drugs and other similar substances.”

Under the law, those caught importing, selling, manufacturing, and using illegal drugs and its forms may be fined and imprisoned for at least 12 years to a lifetime, depending on the severity of the crime.

Since the law was passed at a time the death penalty was still applicable, it is the maximum punishment imposed by the original law. This, however, is moot at present as the death penalty was already abolished in 2006.

If such strict law was passed 14 years ago in 2002, the question remains: Why does the multi-billion drug industry remain unstoppable?

Duterte’s strong drive against drugs has raised more questions than answers involving the measure: Is the law effective? What else can be done? What went wrong?

For Senate Majority Leader Vicente Sotto III, principal sponsor of the law, the legislation is anything but a failure.

Had the law been implemented properly and consistently, Sotto said the country’s drug problem would not be as massive as it is now.

“Kaya lumala hindi inimplementa nang tama ang batas noong mga nakaraang taon. Mula 2002 hanggang ngayon, every now and then parang roller coaster, may panahon na aasikasuhin, may panahon na hindi. Talagang execution ang problema. Ang ganda na nga eh,” Sotto told Rappler.

(That’s why it got worse because the law was not properly implemented in the past year. Starting 2002 until now, it’s like a roller coaster. It’s implemented every now and then, there are times it would be prioritized, there are times not. Execution is really the problem. The law is already good.)

Past administrations had their own respective focus. Now, Duterte’s single agenda of fighting criminality has opened the floodgates of issues that had long been neglected.

Politics? PDEA vs DDB

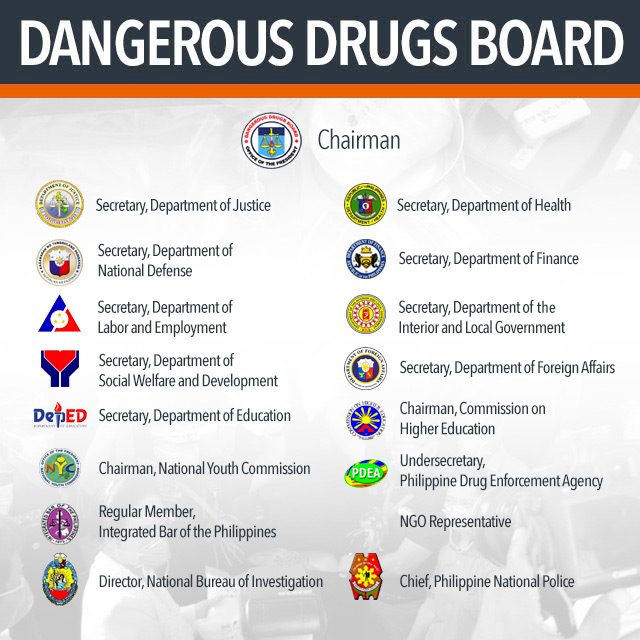

RA 9165 repealed RA 6425 or the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1972. The law mandates the Dangerous Drugs Board to be the policy- and strategy-making body that plans and formulates programs on drug prevention and control.

Article 9, Section 77 of the law states that the DDB “shall develop and adopt a comprehensive, integrated, unified and balanced national drug abuse prevention and control strategy. It shall be under the Office of the President.”

The DDB is composed of 17 members, including the chairman with the rank of Secretary.

The law also created the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA), which serves as the implementing arm of the DDB, and is automatically part of the 17-member DDB.

These two, ideally, work hand in hand to fight drugs. In reality, however, politics and bureaucracy get in the way of things.

The DDB chair has a rank of secretary, while the PDEA Director General is considered an undersecretary. But since it is PDEA that implements the law and does the operations on the ground, Sotto said PDEA tends to reject being under the DDB.

“May leadership problem. Yung PDEA at DDB chair, hindi nagkakasundo. May feeling sila di sila subservient sa isa’t isa. So ang nangyari, ang PDEA feeling nila di sila subservient sa DDB, di nga umaattend ng forum regularly. Magkasama yan sa opisina. Ilang taon yan. Ewan ko kung bakit,” Sotto said.

(There’s a leadership problem. The PDEA and the DDB chairmen are not on good terms. Each of them has a feeling that they are not subservient to each other. So what happens, PDEA feels it is not subservient to DDB, it does not attend regularly. They share the same office. It has been going on for years, I don’t know why.)

DDB Chairman Felipe Rojas Jr, for his part, admitted politics exists inside but downplayed its effect, saying it is not enough to jeopardize the entirety of the anti-drug effort.

“Yung appointment of officials, yung iba hindi qualified, minsan intervention ng pulitika,” Rojas said. (The appointment of officials – some are not qualified, sometimes politics intervenes.)

This does not come as a surprise to some, as such is the situation in most government offices in the country.

Senator Grace Poe, former Senate committee chair on public order, said the track record of appointees should be checked.

“I really think it all boils down to the credibility of the people you will assign in those posts. In the past kasi, mga nandun sa PNP (Philippine National Police), nandun sa iba’t ibang organizations, so sila-sila pa rin (In the past, those from the PNP are also in other organizations, so it’s just always them). I really think kailangan ma-vet mabuti yung Dangerous Drugs Board (I really think those in the Dangerous Drugs Board should be properly vetted),” Poe said.

But while the suggestion is good, the reality is that appointments still depend on one person – the president. He himself chooses who leads the crucial agencies of PDEA and the executive offices that comprise the DDB.

As of posting time, Rojas was already relieved from his post after Duterte ordered appointees of former president Benigno Aquino III to submit a courtesy resignation. The President has now assigned the post to former assistant secretary Benjie Reyes.

As simple as quorum

The politics inside the board may have more repercussions than what meets the eye. Another problem of the board is the lack of quorum, which requires 9 out of 17 members. While it may not necessarily be political, such challenge shows the seemingly shaky dynamics inside, which in turn sheds light on the struggles of policy formation and implementation.

The DDB has 17 members from all aspects of drug rehabilitation precisely because the law wants a holistic approach to the complex drug problem. But while the intent is good, the same could not be said about the agencies involved.

The law mandates that the DDB meet once a week or “as often as necessary at the discretion of the Chairman or at the call of any 4 other members.”

One may call it lucky if the board gets to meet weekly. At the very least, the Board meets once a month, according to Rojas.

Asked if he, as chair, has powers to compel and convince other board members to attend, Rojas only had this to say:

“Very limited, in fact, wala talaga. In some agencies sa abroad, ang DDB ang may hawak ng pondo. As they say, the one who holds the gold rules. Kapag ikaw may hawak ng pondo susunod sa ‘yo yan pero wala sa akin,” he said.

(Very limited. In fact, none. In some agencies abroad, the DDB holds the funds. As they say, the one who holds the gold rules. If you hold the funds, they will follow you but it’s not with me.)

Sotto, former DDB chairman, echoed Rojas’ sentiment.

“’Di nagmi-meet regularly dahilan lagi walang quorum. Hindi uma-attend secretaries. Yung mga secretaries nagpapadala ng undersecretaries, puwede naman yun na representative lang, pero yun mga Usec nila di rin uma-attend eh,” said Sotto.

(The board does not meet regularly, the usual excuse is lack of quorum. The secretaries do not attend. The secretaries send their undersecretaries as their representatives, which is allowed, but the undersecretaries do not attend too.)

The surge in the popularity of Duterte’s anti-drug campaign has given the DDB a huge role to fill, something difficult to accomplish all at once, especially if institutions have long been weak.

“Matagal ang decision-making process – convene the board, magno-notice ka pa. You have to wait for the resolution. Unlike other countries, isa lang ang decision-making at mabilis,” Rojas said.

(The decision-making process takes a while – convene the board, you have to submit notice. You have to wait for the resolution. Unlike other countries, their decision-making process is unified and fast.)

To be concluded – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.