SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

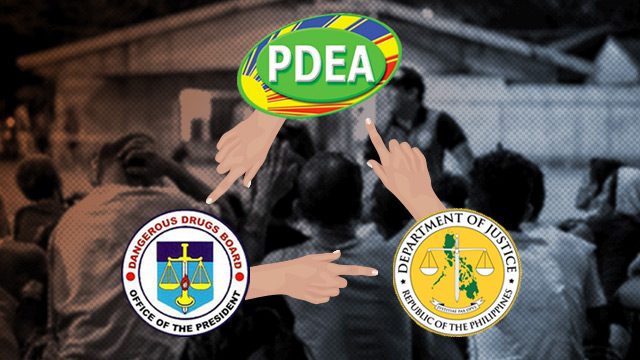

MANILA, Philippines – Consider this: the Philippine National Police (PNP) is at odds with the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA), which is in turn in conflict with the Department of Justice. This, on top of the Dangerous Drugs Board (DDB) having a spat with PDEA.

Senator Vicente “Tito” Sotto III said agencies involved in fighting the war against drugs more often than not resort to finger-pointing. The repercussions are not difficult to imagine.

Sotto said the PDEA dislikes how the DOJ dismisses the many drug cases they file. Citing his experience as DDB chair during the Arroyo administration, Sotto recalled: “Nitong panahon nitong huli, panahon ni Gloria Arroyo, ‘di rin maganda ang relasyon ng PDEA at PNP. Madalas magturuan.”

(During the time of former president Gloria Arroyo, the PDEA and PNP did not have a good relationship. They pointed fingers at each other.)

“Tapos ‘eto pa, PDEA at DOJ hindi rin nagkakasundo. PNP at DOJ hindi rin nagkakasundo. Nabubuwisit ang PDEA dahil nadi-dismiss mga kaso nila. Kaya ‘di maganda tingin sa DOJ. Ang DOJ may record 80% ng kaso dismissed. O sige, ano aabutan ngayon ni Duterte? ‘Di ba, in shambles,” he said.

(Also, the PDEA and DOJ are not on good terms, like the PNP and DOJ. PDEA is annoyed at the DOJ because it dismisses most of the cases filed. The DOJ is put in a bad light because it has a record of 80% dismissal. See, what will Duterte inherit? It’s all in shambles.)

DDB Chairman Felipe Rojas Jr, for his part, said more law enforcers should be trained to address the high dismissal rate of drug cases.

The chain of custody of evidence, he added, suffers because enforcers are not knowledgeable about standards and protocols.

“We need to train more law enforcers in illegal drugs operations kasi maraming drug cases nafa-file ang nadi-dismiss dahil sa investigators (because there are many filed drug cases which end up getting dismissed because of investigators). ‘Yung chain of custody ‘di malinaw (The chain of custody is not clear). Masakit sa ulo dahil mababa ang conviction rate, 10 to 20% (It’s a headache because the conviction rate is low, 10 to 20%),” Rojas said, adding such practice will not deter criminals because of the uncertainty of arrest and conviction.

This is also where corruption enters most, if not all, layers – from operation to investigation and prosecution.

“Nauuwi sa dismissal ng cases (It leads to dismissal of cases). Ang mga pulis ‘di naga-attend ng court hearings (The police end up not attending court hearings). There is also the recycling of shabu,” Rojas said.

To address the problem, Senator Panfilo Lacson said the law should be revised to lessen the difference between the charges of drug use and possession.

“Nakikita diyan nagtuturuan diyan prosecution and law enforcement. Sasabihin ng prosecution, pinahina ‘nyo ebidensya. Sasabihin ng law enforcement, minagic ng prosecution kaya nadismiss,” Lacson said.

(It can be seen that the prosecution and the law enforcement are pointing fingers at each other. The prosecution will tell the police, you weakened the evidence. The law enforcement would tell prosecution that they performed magic that’s why the case was dismissed.)

“Dapat mabawasan ‘yung flexibility ng law enforcement at prosecution para wala masyadong leeway. Kasi ngayon ‘yung drug use and possession ay bailable and non-bailable, malaki na agad diperensya, puwede na pagkaparehan ‘pag salbahe ang prosecution at law enforcement,” he added.

(The flexibility of the law enforcement and the prosecution should be lessened so there would be less leeway. Now, drug use and posession are bailable and non-bailable, respectively. The difference is already big, it could be a venue for corruption for evil prosecution and law enforcement.)

Lacson and other lawmakers have also proposed the exemption of suspected drug lords from the bank secrecy and the anti-wiretapping laws, as big-time operators have resorted to complex and modern means to further their illegal businesses.

To address the seemingly disjointed anti-drug efforts, Sotto has filed Senate Bill Number 3 to create the Presidential Anti-Drug Authority (PRADA), to unify the 4 major programs under a single office – enforcement, prosecution, prevention, and rehabilitation.

It remains to be seen if this measure will become a law as it has to undergo a lengthy legislative process. Even if Duterte himself is a staunch fighter of drugs, his methods in addressing the drug menace are different. As with any measure, the political will of the President is crucial in its enactment.

Funding and rehabilitation

For all their tasks and responsibilities, the DDB and its agencies lack funding to implement the law, especially the rehabilitation aspect, said Rojas. (READ: Rising number of users seeking drug rehab is a ‘happy problem’ but…)

RA 9165 says that drug users and pushers can “voluntarily submit to treatment and rehabilitation.”

Under the law, a drug user who wants to undergo treatment has to secure a police and court clearance to be submitted to the DDB or a DDB representative.

However, not all drug users need to be admitted to centers, according to Rojas. Some may just avail of outpatient procedures depending on the “level” of drug use.

Unfortunately, drug rehabilitation in the country has been least prioritized in the past years, leaving them with less resources and logistics to be tapped as they face a sudden influx of people seeking treatment. In fact, the DDB said there are only 44 rehabilitation centers in the country.

While the responsibility of funding these centers falls in the hands of the Department of Health, the DDB is expected to provide support, especially at the height of Duterte’s anti-drugs campaign.

The problem, however, is two-fold: lack of funding and the spread of limited funds among government agencies.

“Napabayaan talaga ang rehabilitation. Kami sa DDB, binibigyan ng P77 million a year for the construction, repair, and financial assistance for drug rehabilitation and detainees. Kulang na kulang. May budget ang DOH for rehabilitation pero not enough. Kalat kalat din ‘yung budget – DDB, DOH, PDEA,” Rojas said.

(The rehabilitation aspect was really neglected. Here in the DDB, we were given P77 million a year for the construction, repair, and financial assistance for drug rehabilitation and detainess. It’s insufficient. The DOH has a budget for rehabilitation but it is not enough. The budget is also spread out among the DDB, DOH, and PDEA.)

To address the problem – at least for the short- and medium-term – Rojas said the DDB and the DOH have tapped the religious and private sectors to help in drug rehabilitation. (READ: Communities, private sector help is key in nationwide rehab program)

The Christian group Christ’s Commission Fellowship currently helps the government in counseling drug users and pushers, the DDB and the DOH said.

While the DOH gets the blame for the rehabilitation woes, the agency said it has been doing its job even when the drug problem was still off the radar.

In fact, DOH Assistant Secretary Elmer Punzalan said they know the ins and outs of the rehabilitation process as they have long established the Dangerous Drugs Abuse Prevention and Treatment Program.

The problems, Punzalan said, are the lack of funding and the sudden surge of “surrenderees” brought about by the administration’s fight against illegal drugs. (READ: War on drugs: Rehabilitation must be more than a knee-jerk reaction)

“Not true. Kulang lang kami sa pondo. Matagal ng meron pero ‘di kasi sya ang focus ng ibang president. Tanungin ‘nyo kami ngayon alam namin, kasi dati pa namin ito ginagawa. Nagsabay-sabay lang ang kulang ng pondo at biglaang dami ng mga nag-surrender,” he said.

(Not true. We just lack funds. We have long established programs but illegal drugs was not the focus of past presidents. Ask us now, we know what is happening because we have been doing this a long time ago. It’s just that everything happened all at once – lack of funds and the influx of those who surrendered.)

Punzalan said Malacañang has already vowed to give them at least P2 billion to address the rehabilitation problems. But until the money is with them, this amount remains a pledge and nothing more.

If there’s one thing the anti-drug fight has highlighted, it’s that it takes more than legislation to end the menace. While the law imposes strict sanctions on a wide range of violations, the problem lies in the implementation.

In a bureaucracy like the Philippines, where discretion – and, in turn, corruption – is rampant at every stage of enforcement, it may take more than 3 to 6 months to succeed in the fight versus illegal drugs, considering the fact that the 14-year-old law, like most Philippine laws, only got the attention it needs now. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.