SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – The latest word war between Malacañang and Tacloban City over recovery efforts reopened wounds left by Super Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) that had barely healed a year after the tragedy.

On the eve of Yolanda’s first anniversary on November 8, Tacloban Mayor Alfred Romualdez took a swipe at the Aquino government, unsatisfied with how the national government was steering the rehabilitation process: “First of all, why don’t we ask why it took the national government 5 months before we received any kind of financial support?”

On Monday, November 10, rehabilitation chief Panfilo Lacson, sharing President Benigno Aquino III’s sentiment, retaliated with a stinging speech dubbed The Yolanda Report.

“There had been conflicting views whether recovery has been fast or slow,” Lacson said in his speech.

“We’ve been holding our punches,” an exasperated Lacson told media. He accused Romualdez of telling lies and performing below par a year after the disaster.

Recovering on their own

While Romualdez was singled out, mayors in other affected areas actually share the Tacloban mayor’s disappointment.

“They (national government) are not doing anything to begin with. We are recovering on our own,” said Lesmes Lumen, mayor of La Paz, a 5th class municipality about 49 kilometers from Tacloban in Leyte.

Until now, Lumen said, La Paz has not received a centavo from the P50-million recovery plan that the town submitted to the Office of the Presidential Assistant for Rehabilitation and Recovery (OPARR).

According to Lumen, during the critical days after Yolanda, his town received relief assistance mainly from non-governmental organizations and humanitarian groups.

It was only 8 months after Yolanda that La Paz received funds from the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) to rehabilitate its municipal hall, market, and gym – but only about half of the amount needed.

It’s the process

Aquino only approved the comprehensive rehabilitation and recovery plan (CRRP) for Yolanda-affected areas on October 29, almost exactly a year after the killer typhoon.

Sandy Javier, mayor of Javier town in Leyte, told Rappler he understood the delay.

“It’s not accurate to say the government is not doing anything. It’s the process,” said Javier, who also heads the League of Municipalities of the Philippines.

He stressed that his town did its share in complying with requirements, like securing land where new shelters could be built.

“Donors who want to give housing ask us, ‘Do you have property?’ So we buy property. We go to the National Housing Authority for funding to develop the land,” Javier earlier said.

“But they tell us we need a Comprehensive Land Use Plan with geo-hazard mapping. With all the steps we have to undertake, it is just physically impossible for us [to do things] without 3rd party intervention,” Javier explained.

Lacson recognized Mayor Javier as one of the local government executives who had been cooperative with OPARR.

Source of tension

“The closer you are to the ground, the value is more speed. But the farther you are, the value is – well of course speed, but (you do) the right thing. That’s the tension there.”

– Budget Secretary Florencio Abad

However, most LGUs do not have the capacity to comply and rebuild as fast as Javier town did. In many Yolanda-hit towns, housing provision suffered from delays due to search, rescue, and relief operations that lasted for about 5 to 7 months.

According to Budget Secretary Florencio Abad, the national government had to wait for many LGUs until they were able to find land where new shelters would be built.

“The tendency (of LGUs) is to get a settlement area that is free or [affordable]. The problem is those places are near the mountain or the sea,” Abad told Rappler.

The government will not allow that, according to Abad, emphasizing the need to factor in hazards, like landslides and storm surges, in rebuilding efforts.

“The closer you are to the ground, the value is more speed. But the farther you are, the value is, well, of course speed, but [you do] the right thing. That’s the tension there,” Abad stressed.

‘Build back better’

Under the principle of “build back better,” proposals for rehabilitation need to be translated into engineering designs that will reduce risks.

“The requirement is you don’t build like the way you did before. You build to anticipate Yolanda-type calamities,” Abad said.

For instance, buildings to be constructed should withstand storms packing 250-300 kph winds, according to the budget secretary.

The problem is many affected towns, particularly 4th to 6th classes, do not have structural engineers, Abad said.

At least 14 towns in Leyte fall under the 4th or 5th income classes. They usually turn to the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) for expert help. The agency, however, has a limited number of engineers, further delaying the process.

“We need technical skill on the ground: people who can do geo-hazard assessment, land use planners, structural engineers,” Abad said.

Doing it right

Abad also pointed out the uneven capacities of Yolanda-hit local government to absorb funds and implement projects after the disaster.

“When we first received the reports, they were big amounts. And even if there was a list of projects, there was no disaggregation,” he noted.

“Hindi p’wedeng excuse na dahil may calamity, wala kang maipakitang documents (A calamity should not be an excuse for inability to present documents),” Abad said.

But according to La Paz mayor Lumen, he and other mayors have been submitting a lot of documents to get help from the national government.

“Paulit-ulit (Repeatedly),” Lumen complained.

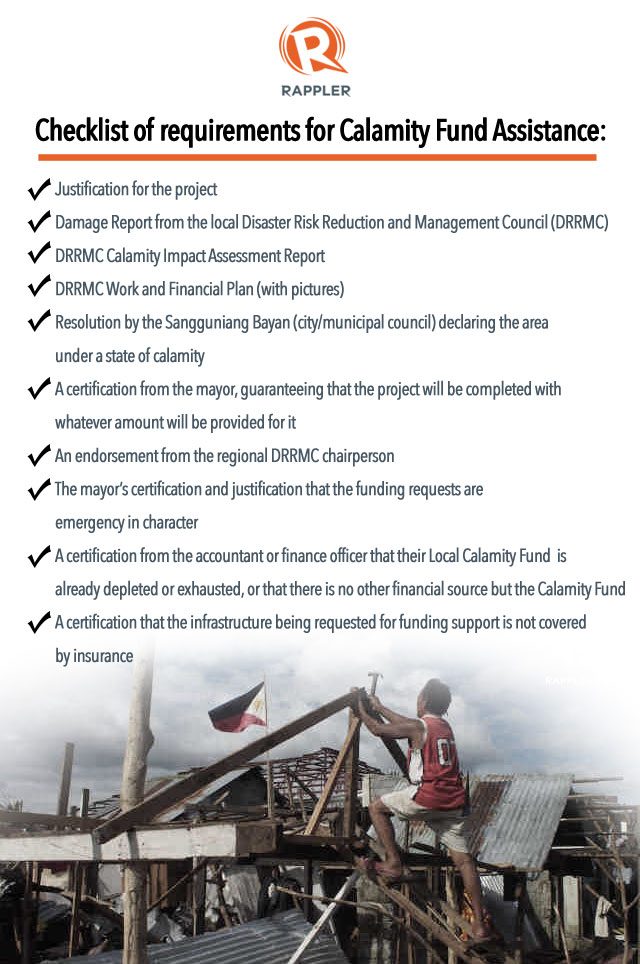

At least 10 documents need to be submitted when requesting for the Calamity Fund Assistance, including a program of work and a financial plan required by the Commission on Audit (COA).

Business as usual

Many Leyte mayors, like La Paz mayor Lumen, claim that exisiting COA rules are another drag on the recovery process. They have raised their concern in various meetings, according to Lumen, who advocates “direct downloading” of rehabilitation funds to local government units (LGUs).

Lumen proposed that funds below P50 million should be directly given to LGUs and communities. Many LGUs had previously demonstrated capacity to implement multimillion-peso poverty alleviation programs and reform initiatives like the Bottom-Up Budgeting (BUB), according to Lumen.

Abad recognized that bringing resources to the ground is the ideal situation, particularly for projects that can be implemented at the grassroots level, like rural health stations.

“If there’s a way that I can directly release to them, and cut, bypass the bureaucracy, that for me is better,” said Abad, who considered the COA issue a continuing challenge.

Abad said there had been a few instances when he was able to do it in the aftermath of Yolanda after a state of calamity was declared. The government asked COA to allow negotiated bids to hasten relief operations, he said.

“The farther you are from ground zero, the less aware you are of the complexities or pecularities of a Yolanda-like calamity. Your tendency is to think business as usual,” Abad said, referring to COA rules.

Political climate

Abad also said not only the disaster, but also the political climate, has traumatized the bureaucracy. The Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF) controversy made officials more rigid in implementing laws, he suggested.

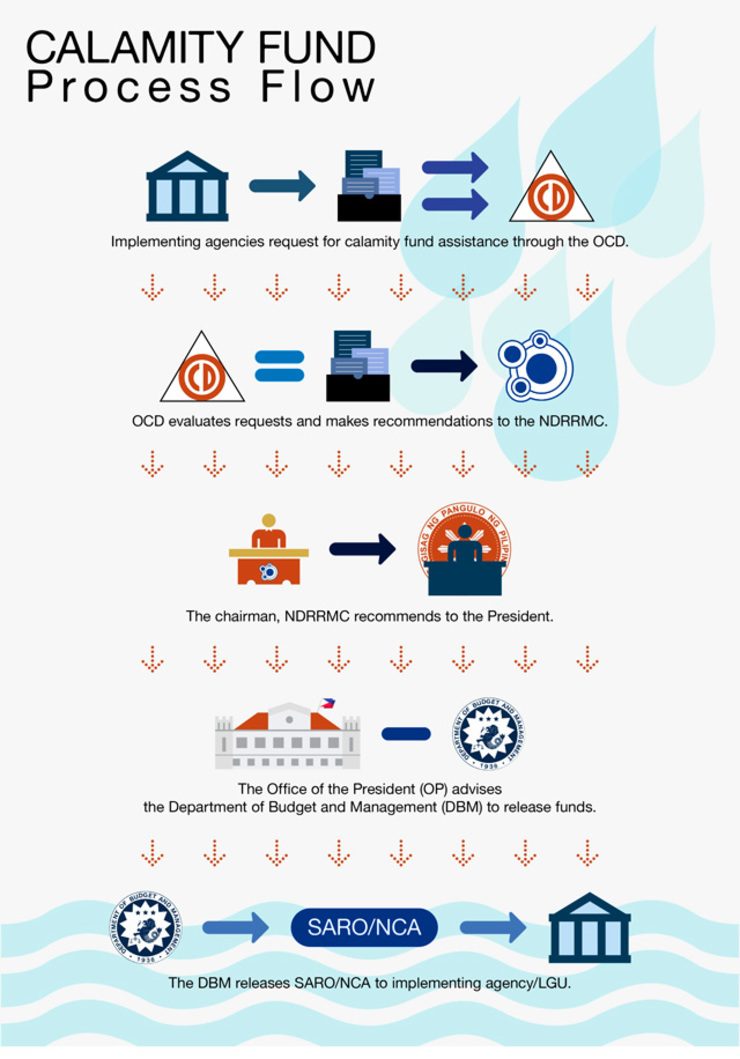

For instance, before his agency could release calamity funds, LGUs and agencies need to follow a tedious and long process in the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) .

“Kung dumaan ka doon, aabutan ka naman ng siyam-siyam,” Abad said. (If you go through that process, it will take longer.)

“That particular process cannot apply to a particular situation that never happened before,” Abad observed.

The budget secretary said the government will review existing processes for dealing with calamities and provisions of relief and rehabilitation. But he conceded that, for now, it has to follow the law no matter how slow. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.