SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Editor’s Note: We are running the first chapter of the book, “Marawi Siege: Stories from the Front Lines” by former Rappler senior reporter Carmela Fonbuena. She weaves together narratives from soldiers in Marawi – from the botched raid to arrest Abu Sayyaf leader Isnilon Hapilon on May 23, 2017 to his death five months later from a sniper’s bullet. Fonbuena was among the first journalists on the ground during the siege of Marawi in 2017. She also spoke to Marawi residents, Maute Group fighters, hostages, local officials, and Moro Islamic Liberation Front members to piece together their accounts and stories. She started working on the book in July 2018 and completed it during the coronavirus pandemic, in between assignments for Rappler and The Guardian. All of 7 parts and 23 chapters, the book will be out this November. Follow latest announcements about it on Facebook.

YEAR 2. Two years after the Marawi Siege, many parts of the city are still in ruins by May 2019. File photo by Bobby Lagsa/Rappler

1:45 pm, 23 May 2017

At the corner of the street, a group of elite soldiers in full battle gear dismounted from three vans. Two boys on the narrow strip stopped dribbling their basketball, frozen as they stared at the troops. Soldiers were a common sight in Marawi City, which hosts Kampo Ranao, the headquarters of the 103rd Infantry Brigade of the Philippine Army, across the street from the provincial capitol compound. But it was likely the children’s first time to see troops from the Light Reaction Regiment (LRR). Members of this United States-trained anti-terrorism unit of the Philippine Army Special Operations Command (SOCOM) could look like soldiers out of a Hollywood war movie because of the gears they carried. Each one, from the commander to the lowest-ranking soldier, wore a helmet and tactical vest. Each one carried a special rifle and other equipment they would rather not divulge.

“Leave now!” a soldier growled at the children, who had stood still all this time. “I’ll shoot you if you don’t leave.” They scampered away.1

The company commander went by the name “Azalea.” The LRR to which they belonged was created in 2001 after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the United States. This elite group plucked its members from other SOCOM units – the First Scout Ranger Regiment and the Special Forces Regiment – and trained them in close-quarter battles to become either snipers or assaulters who would hunt down high-value targets, rescue hostages, and secure presidents and visiting heads of state. It operated under the Joint Special Operations Group (JSOG), a mobile strike force that combined the elite forces of the army, navy, and the air force, and may only be deployed by the chief of staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP). Its accomplishments usually made headlines, but the unit was rarely identified to avoid retaliatory attacks.

Azalea’s team had been in Marawi for more than a month. As Lanao del Sur was increasingly becoming a concern, they were deployed to hunt down followers of the international jihadist organization Islamic State. They raided in April a Maute Group training camp in Piagapo, a town neighboring Marawi City, killing two militant leaders and at least three foreign fighters they coddled.

On May 23, 2017, naval intelligence operatives provided the location of the safe house of Isnilon Hapilon, a veteran fighter who gained world attention after the Islamic State named him the emir in Southeast Asia. This was the kind of mission the LRR was made for.

Outside the safe house, Azalea radioed their arrival to commanders closely monitoring the mission. He called in the first of these radio reports 15 minutes earlier at 1:30 pm, when they started moving from Kampo Ranao. The area was only about three kilometers away from the camp, but traffic was horrendous on the city highway, and the safe house was located deep in a dense residential area.

The raid involved about a hundred soldiers. The LRC was the “main effort” while a team from the Naval Special Operations Group (NAVSOG) – the Philippine Navy SEALs – was “supporting effort.” The Mechanized Infantry Division provided armored vehicles, and one company each from the First Scout Rangers Regiment and the 1st Infantry Division were deployed as “blocking forces.” If this was like previous raids Azalea’s team had led, the soldiers estimated they would be back in Kampo Ranao in two hours. They would enter the safe house, probably fire two shots, and then get the target. But the raid was not to become as successful as troops had hoped. The last report from this mission would be radioed two days later.

Azalea scanned the narrow street to search for the safe house that matched the description he was provided. He was told it was a blue apartment-type house with a black gate. But there was no blue house and there was no black gate. One house in the middle of the street looked like a safe house. It had white walls but the beams were blue. The gate was dark blue, almost black. It had to be it.

The snipers took their positions and assaulters prepared to barge in. On Azalea’s signal, a small explosion forced the gate wide open. Soldiers rushed into the house, parting laundry hanging on overlapping clotheslines, as they made their way to the first door.

One, two, three, four, five assaulters barged in. “Positive. There are guns,” the radio crackled. The guns were on the floor, but there was no living soul in the first room. They moved towards the second room, a kitchen, and that’s when heavy exchange of gunfire ensued.

Bodies crashed to the floor.

The enemies threw an improvised grenade; shrapnel ricocheted off the walls and ceiling.

The military had been hunting down Hapilon for decades in his lairs in the island of Basilan, far away from Marawi City. He was an original member of the country’s most violent and most enduring extremist armed group, the Abu Sayyaf Group.2 It was formed in the 1990s by Middle East-trained scholar Abdurajak Janjalani, a former member of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), once the leading separatist organization in Mindanao that signed in 1996 a landmark final peace agreement that would thrust founder Nur Misuari to become governor of the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM).3

Janjalani and the rest of the ASG originals rejected mere autonomy, however; they insisted on independence. Decades later, some Sulu residents remained sentimental about the ideology that first brought them together. But the ASG did not achieve legitimacy as a rebel organization, and seemed interested only in leaving a trail of violence in its wake, reveling in its global notoriety for launching bombings, kidnappings, and extortion. It was responsible for one of the worst terror attacks at sea in Southeast Asia – the bombing of passenger vessel Superferry 14 that killed 116 people in February 2004.4 It was involved in the “Rizal Day bombings” in Metro Manila in December 2000, a series of explosions that targeted a plaza near the US embassy, the central business district in Makati, the airport, and the metro train.5 At least 22 people were killed and more than 100 others were injured. It raided a luxury resort in Palawan in May 2001 and seized scores of hostages, including an American couple.6 Hapilon’s involvement in the raid put him in the list of wanted “terrorists” by the US Federal Bureau of Investigation, which placed a $5 million bounty on his head.7

The Abu Sayyaf Group had been under constant attack from the military, and many of its leaders were killed through the years. But the group proved resilient, surviving many military chiefs of staff who usually started their terms with promises to wipe out the group. In recent years, the ASG focused on kidnap-for-ransom activities and beheaded foreigners who were unable to meet ransom demands. The criminal activities were so lucrative that many of the group’s members focused on the moneymaking enterprise, resulting in the group growing highly factionalized.

Hapilon was believed to be the leader of the Basilan faction, although he was known to have ambitions bigger than leading the local armed group. He welcomed and nurtured links with foreign groups. It was the one thing that differentiated him from Radullon Sahiron, a fellow original who commanded loose leadership over all the different factions, and who wanted nothing to do with outsiders. There were those who believed Hapilon retained some ideology despite his crimes. It was a reputation helped by a long-held notion that he studied at the University of the Philippines, but the university denied he was ever enrolled in any of its units.

In 2014, Hapilon pledged allegiance to the Islamic State and the black flag.8 It was the same year its leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi appeared on the pulpit of the 800-year-old Grand Mosque of Al-Nuri after conducting a blitzkrieg into Iraq and Syria. Baghdadi declared himself ruler of all Muslims and promised to create a caliphate in the image of the early days of Islam.9

Islamic State lured many Muslims around the world and became the most powerful jihadi force ever seen. In the Philippines, several groups and individuals reached out and sought to establish links, but the jihadist group chose Hapilon and tasked him to establish the Islamic State East Asia wilayat or province.10 Clearly, it didn’t mind that he was more a bandit than a religious or an ideologue.

In December 2016, based on military timeline, Hapilon traveled from Basilan to the town of Butig, 50 kilometers from Marawi City in Lanao del Sur, in mainland Mindanao.11 He joined the young militants of the Maute Group who also pledged allegiance to the Islamic State. Hapilon had set his eyes on the plains of Central Mindanao, where Marawi City was located, to establish the wilayat.

It was here, far away from home, that Hapilon would meet his end at the age of 49, but not on this May 23 mission. The troops would only kill him later. What this mission achieved, according to the military, was to preempt and expose the extent of Hapilon’s grandiose plan to take Marawi City three days later, on May 26, the start of Ramadan.

Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) Chief of Staff General Eduardo Año said the raid aborted the full implementation of a coordinated attack by pro-Islamic State armed groups across Mindanao. That would have been much more difficult for the military to stop.

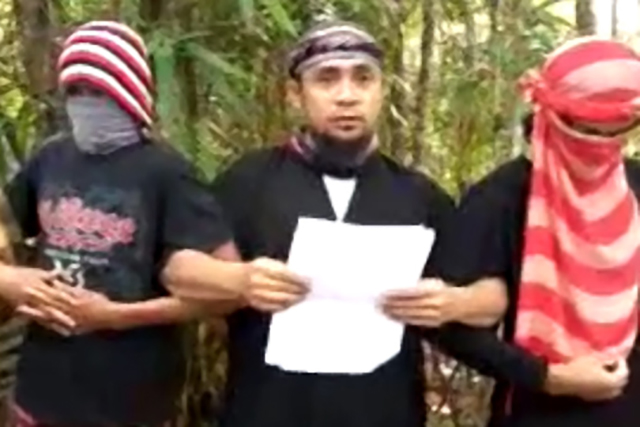

LEADER. An undated photo of Abu Sayaff leader Isnilon Hapilon (center) in Basilan, Mindanao.

8 am, 23 May 2017

Azalea learned about the mission in an early morning briefing on May 23. Intelligence officers from the Western Mindanao Command rushed from the headquarters in Zamboanga City to bring actionable intel on the whereabouts of Hapilon.

Azalea was surprised to learn that Hapilon was the target. There had been no reports on his movements since he was wounded in air strikes in Butig in January. Others presumed he was dead. The intelligence officer said the information required immediate action because Hapilon was security-conscious and made sure he was always moving.

“Can you do it?” Major General Rolando Joselito Bautista, commander of the 1st Infantry Division that supervised the Lanao provinces and the Zamboanga Peninsula, asked the JSOG. The general happened to be in Lanao del Sur that day to supervise a brigade operation against communist rebels in Maguing town. Kampo Ranao commander Colonel Nixon Fortes was in Manila to attend his confirmation hearing in the Senate for his first star as general.

“I think we can do it, sir, but we need more details about the structure so we know what to expect when we get there,” Azalea replied. They had the coordinates of Hapilon’s safe house in Marawi’s Barangay Basak Malutlut, but nothing more. What was the color of the building? What did the neighborhood look like? They checked Google, but it wasn’t helpful either.

“Sir, do you have a picture of the safe house? It’s not clear on Google,” Azalea pressed the intelligence officer.

“We’ll try, sir. The asset is very nervous,” the intelligence officer replied.

“Okay, work on it,” said the general.

The US raid that killed Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden inside his Pakistan safe house in 2012 took months of extensive preparations.12 The Central Intelligence Agency monitored the compound by satellite and conducted surveillance from a local safe house. The agency even organized an elaborate but fake vaccination program to confirm Bin Laden was inside the compound.13

In Marawi, there was no time for proper surveillance. Azalea’s men bombarded him with questions when he gathered to brief them on the mission. Was the structure made of wood or concrete? How many floors, rooms, windows, and people did the building have? Troops needed these details to know how many men they should deploy, what weapons and equipment they should bring, how they were going to move towards the target, and how they were going to extricate themselves from the site. He did not have most of the answers.

While they waited for intelligence operatives to get additional information on the safe house, Azalea and his men rehearsed the order of movement based on a structure they imagined. Who would enter the safe house first? Who would follow? They did not know what to expect, so they brought everything – the full kit of weapons and equipment. They brought explosive charge in case there was something they needed to blow up, and a little chainsaw in case the door had grills. “You have to be prepared for anything that you might find. You have to have your tools within reach,” said Azalea.

At noon, a military asset arrived at the brigade headquarters, turning over a mobile phone used to take a photo of the safe house. Azalea scratched his head. “It was a stolen shot, obviously taken by someone who was very nervous he might get caught,” he said. It showed a part of the gate and a part of the wall. They got little else when they squeezed the asset for more information that might be helpful in the operation. Still, the intelligence officers eventually allowed the asset to guide the troops to the safe house, following desperate pleas from Azalea, to make sure they got to the right location at least. They were going to do this “free flow” style.

At 1:30 p.m. on May 23, a convoy of civilian vehicles left Kampo Ranao. A car carrying the asset and the intelligence officers led the way while the JSOG teams followed. Five minutes later, as planned, armored vehicles moved to follow them. Military trucks carrying one company of Scout Rangers and one company of reconnaissance troops also made their way to designated positions a few blocks from the safe house to serve as blocking forces.

Inside the residential compound in Barangay Basak Malutlut, the lead van carrying the asset snaked its way through narrow roads and stopped at a crossing near the safe house. The driver made three long presses on the brake pad, triggering three red light signals for the JSOG teams behind them. The asset and intelligence officers then left the area.

“Prepare. We’re nearing the target,” Azalea barked to his men.

HAPILON’S SAFE HOUSE. A raid on this safe house in Basak Malutlut on May 23, 2017 triggered the war that dragged on for nearly 5 months. Rappler file photo

2 pm, 23 May 2017

One, two, three, four, five more assaulters rushed into the safe house. The exchange of gunfire grew louder. “Allahu Akbar!” the enemies chanted while they fired their weapons. They had big guns – .30 caliber among them – which made booming sounds distinct from that of bullets fired from smaller arms.

Two soldiers lay dead on the kitchen floor, killed in the first burst of gun battle. A soldier rushed out of the safe house, carrying a colleague on his shoulder. Many were wounded.

Azalea needed bigger guns. He ordered for the armored vehicles, which had stopped on the highway, to join them in the area of the safe house. There was a straight road from the highway to the safe house, which the asset apparently didn’t know about, just wide enough to let the vehicles through. Once in position, the armored vehicles’ .50 caliber guns were fired towards the second floor, where enemies concentrated. The bullets bounced off the concrete walls, however. Azalea was running back and forth on the narrow street, supervising the troops and coordinating the evacuation of the wounded.

It was clear the enemies were prepared for the raid. While one group of soldiers exchanged heavy gunfire with the occupants of the safe house, another moved to gather their casualties at a designated collection point in an adjacent house.

Pauses in the gun battle made the soldiers think the enemies had run out of ammunition, but bullets came flying again whenever they made attempts to maneuver towards the second floor of the house. “They mounted an impressive defense. They kept attempting to get out of the door to spray fire. They were brave. They probably thought there were only a few of us,” said Azalea.

The situation escalated at around 4 p.m., when the neighbors started sniping at troops. Azalea couldn’t move as easily on the street anymore. It showed signs of pintakasi, he said, where pinned down enemies would get reinforcement from relatives in the neighborhood. It was an enemy tactic that had killed too many soldiers in the jungles of Sulu and Basilan. The military didn’t see it coming in the urban terrain of Marawi City, although locals said they were not surprised that Hapilon would make sure to surround his safe house with his men.

Watching the enemies exchange gunfire with the armored vehicles, Azalea was stunned by their grit. “They were very daring,” he said. They managed to shut down one armored vehicle, disabling the rotating turret that carried the gun. Another suffered a flat tire, leaving troops with only one armored vehicle. The two damaged vehicles returned to the brigade headquarters at around 5 p.m., carrying the first batch of eight wounded men.

Troops couldn’t pull out the bodies of two dead soldiers from the safe house because of the heavy volume of gunfire. They forced the remaining armored vehicle to turn around so its back door would face the gate of the casualty collection point. That would allow them to move wounded soldiers into the vehicle without getting shot. But the vehicle got stuck diagonally on the narrow street. The gunner kept the turret on the target as the driver tried to maneuver.

The NAVSOG dealt with the snipers outside the safe house, allowing the LRC to focus on the target.

Pause. Volume of fire. Pause. Volume of fire.

They couldn’t move the armored vehicle anymore. Azalea requested for another one to evacuate the casualties. Several soldiers were seriously wounded and needed immediate medical attention. When the request seemed to be taking long, he snapped over the radio. “Where’s my armored vehicle, sir? Why is it taking so long?” Called only for priority missions, the JSOG is a spoiled unit in the military. Whatever LRR wants, LRR gets – most of the time, at least. He couldn’t understand why the armored vehicle had not arrived. Was there a mission more important than theirs?

“Buddy, it’s not just us. Other troops are also engaged,” he was told on the radio. From the safe house, Azalea and his men had been hearing gunshots and explosions erupting elsewhere in the city. There was a plume of smoke in the distance and he learned on the radio that a detachment was burning.

“We weren’t the priority mission anymore. Something bigger was going on,” said Azalea.

All hell had broken loose on the city. – Rappler.com

1 Light Reaction Company commander “Azalea,” interview by the author, Aug. 1, 2018.

2 Ressa, Maria. Seeds of Terror. Free Press, 2003.

3 Marites Vitug and Glenda Gloria. Under the Crescent Moon: Rebellion in Mindanao. Ateneo Center for Social Policy and Public Affairs, 2000.

4 Associated Press, “World Briefing | Asia: The Philippines: Bomb Caused Ferry Fire,” The New York Times, October 12, 2004. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/10/12/world/world-briefing-asia-the-philippines-bomb-caused-ferry-fire.html.

5 Agence France-Presse, “Timeline of deadly bomb attacks in Manila, ABS-CBN News, November 29, 2016, https://news.abs-cbn.com/focus/11/28/16/timeline-of-deadly-bomb-attacks-in-manila.

6 Carlos Conde, “Members of the Phillipine extremist group Abu Sayyaf in court Thursday awaiting the verdicts,” The New York Times, Dec. 7, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/07/world/asia/07philippines.html.

7 Carmela Fonbuena, “Abu Sayyaf top man Sahiron sends surrender feelers – military,” Rappler, Apr. 18, 2017, https://www.rappler.com/nation/abu-sayyaf-radullon-sahiron-surrender-feelers-military.

8 Maria Ressa, “Senior Abu Sayyaf leader swears oath to ISIS,” Rappler, August 4, 2014, https://r3.rappler.com/nation/65199-abu-sayyaf-leader-oath-isis.

9 Who was Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, BBC, Oct. 28, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-50200392.

10 15 terrorists killed as bombs dropped on Hapilon’s lair: AFP, ABS-CBN News. Jan. 29, 2017, https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/01/29/17/15-terrorists-killed-as-bombs-dropped-on-hapilons-lair-afp.

11 Associated Press, “Top Abu Sayyaf leader hurt in airstrike – defense chief,” Rappler, Jan. 28, 2017, https://www.rappler.com/nation/top-abu-sayyaf-leader-isnilon-hapilon-wounded-airstrike-lorenzana.

12 Minutes and Years: The Bin Ladin Operation, Central Intelligence Agency, April 29, 2016. https://www.cia.gov/news-information/featured-story-archive/2016-featured-story-archive/minutes-and-years-the-bin-ladin-operation.html

13 Saeed Shah, “CIA organised fake vaccination drive to get Osama bin Laden’s family DNA,” The Guardian, July 11, 2011, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/jul/11/cia-fake-vaccinations-osama-bin-ladens-dna.

This book was funded by the Australian government through the Australian embassy in the Philippines and the non-profit German foundation Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung (FES). The views expressed here are the author’s alone and are not necessarily the views of the Australian government nor FES. The Australian government and FES neither endorse the views in this book, nor vouch for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained within. The Australian government and FES, their officers, employees and agents, accept no liability for any loss, damage or expense arising out of, or in connection with, any reliance on any omissions or inaccuracies in the material contained in this book.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.