SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

First of 3 parts

Part 2: Elections and the Estrada wealth

Conclusion: Remember the ‘Boracay Mansion’?

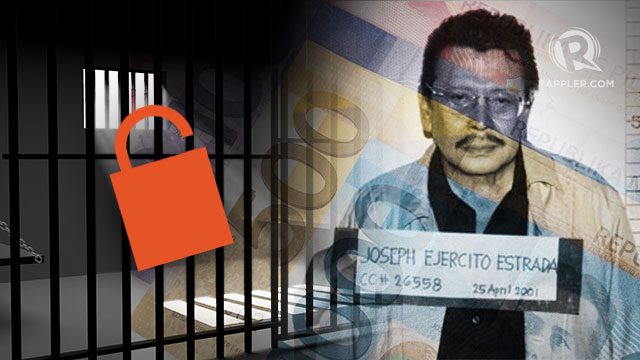

MANILA, Philippines – It was a scene that put all his cinematic exploits to shame: holed up in his sprawling residence in Greenhills, San Juan City, with hundreds of supporters outside, former President Joseph “Erap” Estrada was finally served with an arrest warrant, taken to Camp Crame, and was required to undergo the routine mug shot after he was indicted for plunder before the Sandiganbayan.

The April 25 arrest marked a new low to the political career of the man who captured the presidency in 1998 via a landslide victory. Three years later, in January 2001, he was ousted in a popular revolt following an aborted impeachment trial where he stood accused of illegally amassing wealth through kickbacks and commissions from jueteng operations, stocks manipulation, and tobacco excise taxes.

That chapter in his life happened 13 years ago, with the ultimate humiliation angering his supporters who staged their own version of an EDSA uprising. For 6 days, they occupied the EDSA Shrine in a futile attempt to duplicate the scene that ousted their hero. Finally on May 1, they marched to Malacañang to force the issue.

Unlike the more organized and less spontaneous EDSA 2, however, EDSA 3 failed to reclaim the presidency for Estrada.

With Estrada’s arrest, many thought that a new political order had begun, where public officials are finally held accountable for their misdemeanor. But Estrada’s plunder case and the political scandals that followed showed that political maturity remained a pipe dream.

“At that time, it sent a chilling effect to our public officials. But that fear slowly faded away,” observed political analyst Allen Surla. Erring public officials, if at all, have just become more careful this time, Surla added.

More than 6 years later, in 2007, Erap was found guilty for the crime of plunder by a special division of the Sandiganbayan, which also ordered the forfeiture of his illegally acquired wealth. But the seemingly Teflon-coated Erap Estrada still managed a strong 2nd place finish in the race to the presidency in 2010.

Today, Erap has made a political comeback of sorts, but not in the grand scale he had probably hoped for. Still, it was nothing short of spectacular. Consider the following:

- He has his own kingdom, as mayor of Manila, with neighboring San Juan City under the control of his mistress, Guia Gomez. Their son JV Ejercito was elected senator in the 2013 midterm race, joining his half-brother Jinggoy Estrada, who is on his second and last term as senator.

- Financially, despite being under hospital arrest for 6 years and the forfeiture of illegally-acquired wealth, Erap has rebounded with a vengeance. From a net worth of P35.86 million in 1999 (or US$900,000 based on 1999 conversion rates; his wife, Senator Luisa “Loi” Estrada, declared a net worth of P34.41 million or $700,000 in 2006), Erap’s net worth as of July 2013 jumped to P244.21 million ($5.8 million), or close to a 600% increase – based on his Statement of Assets, Net Worth and Liabilities (SALN). This is over a 14-year period encompassing two presidential elections.

- With his still huge following among the poor, he remains a “king-maker” whose clout could still dictate the outcome of the upcoming 2016 presidential race.

His immediate potential successor, Jinggoy, has announced he is open to seeking a higher post, the vice presidency, which Erap had also occupied before his ascent to the presidency. Jinggoy has been faithfully following his father’s footsteps – as mayor of San Juan and then as senator.

But the curse of the number 13, which the superstitious Jinggoy considers his unlucky number, has surfaced once again. Jinggoy is facing his 2nd plunder charge courtesy of the pork barrel scam. In 2001, he was co-accused with his father, also for plunder, but he got acquitted. (READ: How Jinggoy got away in his first plunder charge)

Like the Napoles pork barrel case

Filed in April 2001, Erap’s plunder case draws a striking similarity with the Janet Lim Napoles pork barrel scam, 13 years after:

- Some members of the supporting cast in both scandals immediately fled the country or went into hiding. In the Joseph Estrada plunder case, only businessman Jaime Dichaves surfaced, but only he (Erap) made a triumphant return to politics. (READ: Cast in Erap plunder case: Where are they now?)

- To tighten its case, the government provided legal refuge to those involved in the Erap plunder case, in particular, Ilocos Sur Governor Luis “Chavit” Singson, who was granted legal immunity. In the pork barrel case, Napoles’ erstwhile right-hand man Benhur Luy, was also given the same privilege.

- Like Singson, Luy also kept a ledger detailing the different transactions of lawmakers with Napoles.

- Trusted associates in both scandals betrayed their principals. Jinggoy’s own version of Charlie “Atong” Ang – who entered into a plea bargain and offered to return P25 million of his kickbacks in his father’s case – is long-time family friend Ruby Tuason who offered to testify against him and return P40 million in kickbacks.

- As in Erap’s case, Senators Jinggoy Estrada, Ramon “Bong” Revilla Jr and Juan Ponce Enrile said the pork barrel case is politically motivated to deplete the opposition ranks for the 2016 polls. Plunder being a non-bailable charge, they face possible arrest if indicted.

In all likelihood, the pork barrel case could even be tried side by side with the Erap plunder case, which is still being heard by the Sandiganbayan. Contrary to general perception, the Erap plunder trial is not yet a terminated case, as some of the accused who went into hiding are still facing charges.

Dichaves has been granted by the Supreme Court a reprieve that delayed his arraignment, while Yolanda Ricaforte, Erap’s alleged bagwoman, has been issued a fresh arrest warrant after twice failing to attend a scheduled arraignment.

Forfeited assets, forfeited chances

On April 19, Erap celebrated his 77th birthday. By all indications, he is enjoying a new lease on his political career, salvaging what could have been a bad script in his public life. The former action star was written off as a spent force, only to prove his critics wrong.

While he now shares the resumé of former convicts granted pardon by former president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, Erap is still the last one laughing his way to the bank. The facts behind his forfeited assets tell a different story:

- He may have lost prime real estate property that was built for a beloved mistress, but got away with the other houses he supposedly accumulated while in office.

The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) found that Erap, in his two-and-a-half years in office, was able to accumulate, through his dummies, more than P2-billion worth of real estate properties. PCIJ said Erap “acquired 17 pieces of choice property in Metro Manila, Baguio and Tagaytay” with only a measly P35.8 million net worth based on his 1999 SALN.

Built for former starlet Laarni Enriquez, the “Boracay Mansion” in New Manila, Quezon City, is the only one real property forfeited by the Sandiganbayan. The prosecution was able to prove that money used to purchase the property, amounting to P142 million, was traced to the Jose Velarde account. The court said: “The documents found in the Boracay mansion show that the beneficial owner of the Boracay mansion is FPres. Estrada and is used by Laarni Enriquez whose relation to former Pres. Estrada was never denied.”

Retired Special Prosecutor Dennis Villa-Ignacio, who helped pin down Erap, said the prosecution did not go after his other real properties as a matter of strategy. “It is the property where we have evidence linking it to Estrada’s dummy account,” he said in an interview.

Based on the September 2013 compliance report submitted by Sandigan acting chief judicial officer Albert dela Cruz, there’s still a balance of P417.86 million (about $9.3 million at current exchange rates) to be collected from Estrada. The breakdown is listed below. Court records showed that the amount to be forfeited against Estrada totaled about P735 million (roughly $15 million in 2001). However, only about P317 million has been recovered by government.

- Out of the P545.29 million (inclusive of interest and income earned) deposited in the name and account of the Erap Muslim Youth Foundation, only P215.83 million has been surrendered to the Sandiganbayan as of September 2013, leaving a balance of P329.46 million.

- Of the P189.7 million (inclusive of interest and income earned) ordered forfeited in the Jose Velarde account, only P101.3 million in hard cash has been handed over to the anti-graft court, leaving a balance of P88.4 million.

In a November 27, 2007, report to the court sheriff, Equitable-PCIbank (now Banco de Oro or BDO) said that “the updated balance of the (Erap Muslim Youth) Foundation was only P215.83 million instead of the original amount of P545.291 million.”

The Jose Velarde account itself has an outstanding balance of only P100.93 million with a maturity value of P101.27 million by the time the anti-graft court sought its forfeiture. All in all, what was left was roughly over P300 million, or less than half of what the prosecution estimated should be forfeited in favor of government.

What happened?

It appears that before a freeze order was issued on the two accounts – Erap Muslim Youth Foundation and the Jose Velarde special deposit account – by the time the Court issued its ruling, some of the money had already been withdrawn.

The Erap Muslim Youth Foundation account had been identified as the repository of jueteng proceeds remitted by Singson to Erap. Singson said he remitted P200 million to the Foundation’s account at Equitable-PCIBank.

The Jose Velarde account, on the other hand, was the repository of commissions received by Erap from the sale of Belle Corporation shares. Erap ordered the Government Service Insurance System and the Social Security System to purchase Belle stocks amounting to P1.102 billion in exchange for the commission.

Estrada has denied owning the Jose Velarde account, and pointed to his crony Dichaves as the actual owner. The anti-graft court, however, was not persuaded by Estrada’s claim, and was convinced he “was the real and beneficial owner.”

Hidden assets

How then could the government offset the remaining amounts to be forfeited?

The answer lies in the Wellex and Waterfront stocks which were part of the assets uncovered in an Investment Management Account (IMA) under the name of Jose Velarde and being managed by then Equitable-PCIBank (BDO is now the successor in interest of Equitable-PCIBank).

Consisting of 450 million shares of Waterfront Philippines and 300 million shares of Wellex Industries, the stocks were used as collateral for a P500-million loan that plastics king William Gatchalian obtained from Equitable-PCIBank in 2000. As of 2008, the total Wellex and Waterfront shares were estimated to be worth P652.5 million.

During the trial, it was established that the source of the loan was IMA Trust Account No. 101-780-56-1 under the name of Jose Velarde. How the loan was effected provided the dramatic twist that hastened Estrada’s fall from grace.

Jose Velarde account

In the impeachment trial at the Senate in 2000, former Equitable-PCIBank chief trust officer Clarissa Ocampo testified that she saw Estrada sign as “Jose Velarde” in bank documents. The House prosecution team then submitted a sealed envelope that purportedly would prove that Estrada was the real owner of the Jose Velarde account.

Estrada’s allies in the Senate voted not to open and accept the sealed envelope as part of the impeachment evidence, triggering a walkout of the House prosecution panel. This sparked EDSA 2, which nailed Estrada’s downfall.

At the Sandiganbayan, Ocampo testified that among the documents Estrada signed as Jose Velarde was a debit-credit authority which facilitated the P500-million loan to Gatchalian. Estrada himself admitted before the court that he signed as “Jose Velarde” – “an admission against self-interest” which, to the court, provided “the best evidence” that he was the actual owner of the Jose Velarde account.

Estrada told the Court that the loan was an “internal arrangement” with Gatchalian, who was one of his major donors in the 1998 elections. In extending the loan, Estrada told the court that he was only trying to help Gatchalian and his thousands of employees who risked losing their jobs if the businessman failed to get the capital infusion.

“At inisip ko rin na wala naming (sic) government funds na involved kaya hindi na po ako nagdalawang-isip na pirmahan ko,” Estrada told the court, in reference to signing as Jose Velarde to effect the loan. (And I thought that since government funds were not involved, I did not have second thoughts about signing.)

These unknown assets under the Jose Velarde account were discovered only in January 2008 when BDO submitted its report on the Jose Velarde account to the Sandiganbayan. In a fortuitous circumstance, the assets were left untouched due to a constructive distraint order issued by then Internal Revenue Commissioner Lilian Hefti in January 2001.

The constructive distraint order, which effectively stopped the dissipation of assets in the Jose Velarde account, was in connection with the tax deficiency assessment issued by the BIR on Erap and his wife, Luisa “Loi” Ejercito.

To cover the remaining balance, the government sought the forfeiture of the locked assets in the Jose Velarde account. Ironically, Erap himself was instrumental in the eventual forfeiture of Gatchalian’s mortgaged shares of stocks.

Shortly after the Sandiganbayan issued the writ of execution for the forfeiture of his illegally-acquired assets, Erap sought to contest the court order, alleging the writ was flawed since it covered assets he acquired when he was not yet president.

The Sandiganbayan agreed, prompting it to amend its original ruling. Instead of going after Erap’s assets, which he accumulated before he became president, the anti-graft court said that in the event “that the amounts or property listed for forfeiture in the dispositive portion be insufficient or could no longer be found,” the court sheriff “is authorized to issue notices of levy or garnishment to any person who is in possession of any and all forms of assets that is traceable or form part of the amounts or property which have been ordered forfeited by this Court.”

In particular, the court cited the receivables and assets found in the BDO Trust Account under Jose Velarde’s name, under which Gatchalian’s Wellex and Waterfront shares were parked as collateral to the P500-million loan earlier secured by the businessman from the Velarde IMA account.

Gatchalian, through his Wellex Company, sought to claim the mortgaged shares and went to the SC to contest his stocks’ forfeiture. The High Tribunal, however, sided with the anti-graft court.

Despite the court case, Erap and Gatchalian remained on good terms. The businessman, in fact, even gave a P10-million donation to Erap’s doomed campaign to retake Malacañang in 2010.

No closure

Far from being closed, Erap’s plunder case remains an active one, with the members of the Sandiganbayan special division having been replaced. At present, the special division is chaired by Justice Jose Hernandez, with Justices Napoleon Inoturan and Maria Cristina Cornejo as members.

What lessons can be drawn from the Erap trial that the pork barrel plunder case can learn from?

- Potential state witnesses granted broad immunity may still change their tune. In the case of Belle Corporation, where Estrada supposedly got P189.7 million ($4.6 million, at P41:$1 in 1999) in kickbacks when he ordered the SSS and the GSIS to purchase the gaming firm’s stocks, former SSS president Carlos Arellano and former GSIS president Federico Pascual maintained that the transactions were above board.

What saved the prosecution from losing the case was their testimony that Erap repeatedly called and ordered Pascual and Arellano to push through with the transaction.

Willy Ocier, chief executive officer of Belle Corporation, now maintains in an affidavit executed Jan 10, 2012, that he had “no direct encounter” with Dichaves, who served as broker between him and Erap for the stock purchase. But earlier, during the trial, Ocier said he gave a P200-million kickback intended for Estrada to Dichaves. Dichaves is now using Ocier’s new affidavit to extricate himself from the plunder charge.

- With no case filed yet before the Sandiganbayan, there is high probability that the repositories of the ill-gotten wealth of those involved in the pork barrel scam may have been dissipated by this time, especially for those whose bank accounts have not been subjected to a freeze order. At the start of the Erap plunder trial, the prosecution estimated that the Jose Velarde account was worth P3.2 billion (about $63.7 million in 2001) but the money was stashed away before the Court could issue a freeze order.

- Flight may be an indication of guilt, but it can buy time for the accused in the pork barrel case. They can always claim they had been denied due process, which was what Ricaforte and Dichaves did, keeping them away from jail, at least in the meantime. In fact, Dichaves is back partying with Erap.

- With only Erap, Jinggoy, and lawyer Edward Serapio as defendants in the plunder charge, it took the special division of the Sandiganbayan 6 years to resolve the case, even with a fast-paced trial. In comparison, the pork barrel case involves more than dozens of accused, raising the possibility of a protracted and longer trial than Erap’s.

Political analyst Ramon Casiple opined that Erap was able to make a comeback despite his conviction because the circumstances of his case were different from those of the pork barrel case. “[Erap] Estrada was tried for jueteng and not pork barrel,” he said.

Still, the common denominator in both cases is corruption and Erap’s case serves to heighten public awareness about it. “It is not true that the issues do not stick. Corruption is still an issue,” Casiple said, asserting that it has somehow affected Erap’s popularity.

The results of the 2016 polls will either prove or disprove Casiple’s theory. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.