SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story said Balangiga Encounter Day was commemorated starting 2008. It also said that the estimated number of civilians killed amounted to 10,000. These have been corrected.

MANILA, Philippines – The Balangiga Massacre was one of the bloodiest events during the Philippine-American War.

To this day, the United States considers this as their “worst single defeat” in the history of the 3-year war from 1899 to 1902. The Philippines has also not forgotten.

Republic Act 6692 enacted on February 10, 1989, declared September 28 of every year as “Balangiga Encounter Day,” a special non-working holiday in Eastern Samar to commemorate the uprising of fellow Filipinos and to honor the gallantry of those killed.

In 2008, however, Malacañang issued Proclamation No. 1629 moving the commemoration of Balangiga Encounter Day that year to September 30. The provincial government had requested this, since September 28, 2008, fell on a Sunday. Eastern Samar officials believed the province and its people would be given the “full opportunity” to observe the occasion if it were held on September 30, 2008, a Tuesday.

Here’s what you need to know about the Balangiga Massacre:

Why it started

In the beginning, residents of Balangiga town and Company C, the 9th US infantry regiment, had a good relationship. According to historians, relations went downhill after two American soldiers allegedly tried to molest a Filipino woman tending a store.

When locals came to the woman’s defense, the soldiers wanted revenge. Since then, people in Balingaga were subjected to forced labor and detention with only little food and water.

The locals also protested the move of the US garrison to cut food and other supplies in the town.

Balangiga police chief Valeriano Abanador, along with guerilla officers Captain Eugenio Daza and Sergeant Pedro Duran Sr, plotted the uprising against the Americans.

According to historian Stuart Miller in his book Benevolent Assimilation, Balangiga men disguised as women hid weapons inside small caskets which were brought to the church under the pretext that a cholera epidemic had killed many children.

Reinforcements from neighboring towns also entered Balangiga several days before the attack under the guise of preparations for a fiesta.

How it happened

The plan was executed on September 28, 1901, during the supposed funeral procession for children killed by cholera. Abanador initiated the first strike by shooting an American sentry after chatting with him.

The church of Balangiga rang its bells, signaling the start of the attack. The men dressed as women pulled out their weapons – mainly machetes – and attacked the US troops. Locals also headed to the barracks to attack unsuspecting American soldiers.

At least 48 out of the 78 American soldiers were killed during the surprise attack.

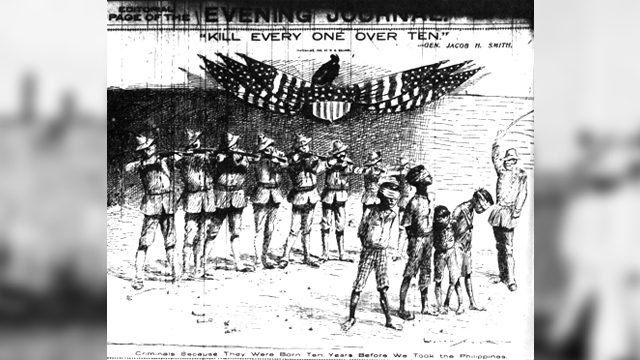

The following day, American forces decided to retaliate. General Jacob H. Smith vowed that he would turn the town into a “howling wilderness,” earning him the nickname “Howling Jake.”

“I want no prisoners. I wish you to kill and burn. The more you kill and burn the better it will please me. I want all persons killed who are capable of bearing arms in actual hostilities against the United States,” Smith said.

Smith’s remark became even more infamous when he instructed his men to “kill everyone over 10.” Soldiers also burned and looted the villages in Balangiga.

The killings did not end there, as the US continued to enforce a “scorched-earth policy” until 1902, which meant the total destruction of the town and its people.

There is no exact estimate on the number of Filipinos killed, despite what some resources have previously said that about 2,500 were killed during the duration of the massacre.

Recent study by the Balangiga Research group found that most soldiers “counter-manded” the kill-and-burn order, which meant that some soldiers refused to claim innocent lives and resorted only to destruction of homes and livelihood.

The Americans brought home the church bells of Balangiga as “trophies of war.” Two are under the custody of US troops in the “Trophy Park” of the Francis E. Warren Air Force Base in Wyoming, while the other is with the US military unit in South Korea.

Moves to return the bells

The Philippines has been asking for the return of the bells as early as 1958, when Jesuit priest Horacio dela Costa wrote a letter to American military historian Chip Wards seeking help for this purpose.

President Fidel Ramos was the first Philippine president to negotiate the return of the bells with a US President, Bill Clinton, who agreed to the request. However, the return was stalled due to an apparent conflict in US military laws.

In his 2017 State of the Nation Address, President Rodrigo Duterte asked the US to return the bells as they are “reminders of the gallantry and heroism of our forebears who resisted the American colonizers and sacrificed their lives in the process.”

On August 11, 2018, the US embassy in Manila announced that the US defense department had notified the US Congress of its intention to return the bells to the Philippines, but no date had been set. The return of the bells needs congressional concurrence.

Some US veterans groups and lawmakers are opposed to the move, as the bells are seen as memorials to fallen US soldiers.

After more than a century, will the bells finally return home? – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.