SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

In the quest to follow the story of Eudocia Tomas Pulido, the Filipino maid called a slave by the child she took care of, I drove to Mayantoc, Tarlac, on Saturday, May 20 to see if there are stories there. Mayantoc is not hard to find. It may be in the hilly part of the province but it follows a straight road from the city proper.

There’s another reason why I found Mayantoc with ease. Tarlac is my hometown, having been born and raised in the town of Moncada until I went to Manila for college and for work.

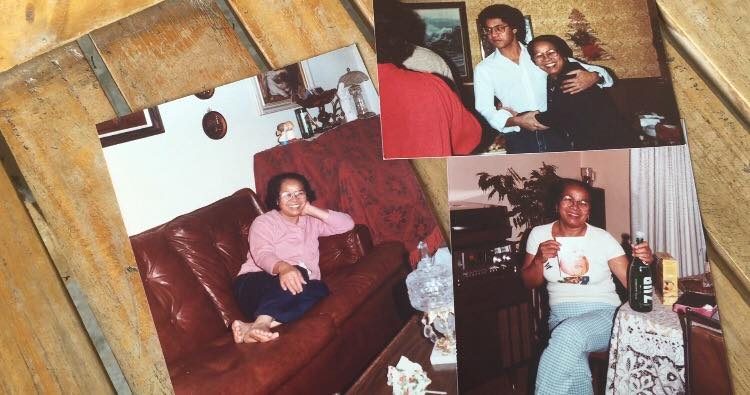

In Moncada, you would find almost every family, or someone who knows someone who knows that family, in the town market. I found two of Eudocia’s nieces instantly in the market’s vegetable section – 56-year-old Norma Julian is a vendor while 64-year-old Rosita Labador was just passing by.

I asked them whether they know Eudocia Pulido. Yes, they said, and to them, she’s Aunt Cosiang: someone they knew to be in America, someone they saw only in photos when they were little, and someone who helped them when she was finally able to earn money as a nanny to a Filipino-American family. (WATCH: ‘Slave’ Eudocia is ‘Cosiang’ to her family)

Journalist Alex Tizon wrote the account of Cosiang’s life for The Atlantic, in a piece called “My Family’s Slave,” that opened a floodgate of debates on modern-day slavery, migration, and even race. Tizon lovingly wrote about his “Lola,” but didn’t hold back in describing the cruelty that Cosiang suffered in the hands of his parents.

Apart from not being paid for 56 years, Cosiang was precluded to have a life outside the Tizon home, and was always scolded even when she was sick.

Aunt Cosiang

Norma and Rosita said they didn’t know this. “Wala namang communication e (There was no communication),” said Rosita, the daughter of Cosiang’s sister, Maxima. Norma, the daughter of Cosiang’s brother, Crispin, said their Aunt Cosiang didn’t say much about the Tizons in her homecomings in Mayantoc. (READ: The Atlantic’s ‘My Family’s Slave’ should not end with a feast)

If there were any stories, Norma said, it was about Alex’s kindness. When his parents died, Alex took care of Cosiang, helped her get amnesty to be able to stay in America, and started paying her $200 a week, though he said he made it a point that Cosiang was no longer treated as a slave.

This was around the time that Aunt Cosiang finally started sending money to Mayantoc. Norma’s children were among those the old woman helped. But they also recall the hard times when Cosiang’s parents needed money but the aunt they knew to be in the land of opportunity couldn’t pitch in.

“Nakakaawa nga ang nararamdaman namin kasi ang tagal-tagal doon, wala man lang napagawa dito o napagkakitaan na galing siya sa abroad,” Rosita said.

(We feel sorry for her because she spent a long time in America, but she wasn’t able to build something here, nothing to show for her time abroad.)

Filipino helpers

This, I understand. The phrase “katas ng abroad” or “the fruits of overseas labor” is all too familiar to me. I grew up in a clan of overseas domestic helpers. My mother was a domestic helper before she became a caregiver, her job to this day.

Being a katulong, a yaya or a house help was never a point of shame in our family. It is in fact almost an aspiration even down to some of my cousins now. If you become a househelp overseas, it means your family back home will have a sure shot at a good future.

It means a nice house; even a mansion. It means college education for all the children. More importantly, it means citizenship in whatever country which will pave the way for more overseas-bound family members. For what job? Whatever job. “Basta makapag-abroad lang (whatever will take me overseas).”

My 24-year-old cousin, even with a college degree, has been working on getting a visa to Canada where she’s willing to be a helper. Her younger sister, who had just graduated with a degree in business, would also quip that she’s willing to follow this path.

This is the culture I grew up in; poverty that imposed on us the kind of dream that had everything to do with money, not passion. But it’s because of this drive that we are able to survive.

Helpers among families

The Tizons were distant relatives of Cosiang. Norma and Rosita explained that it never entered their minds that their aunt was being subjected to what can only be described as slavery, because the people who took her were family. They were sure she was in good hands. (READ: We are all Tizons)

This, I understand too. In the province, your house help are your relatives. You either pay them in the normal way, a monthly salary or you pay them through other means – either you send them to school, or your child would get free lodging with relatives instead of rent a dorm for college.

I know because this is the scheme in my clan. The dynamics of our clan is very similar to the Pulidos, I have observed. Some members are comfortable, owing largely to the number of children who are overseas, while some stay below average.

In the Pulido clan, the members range from owners of a large mansion to a box house, from hardware shop owners to cashiers.

In this kind of setup, the “rich” ones help the ‘poor.’ For the Pulidos, it was the Tizons who took Cosiang, and another one of her nieces, Ebia, who said she left because she found other jobs that actually paid.

The woman who took care of me was a distant relative we called Manang (Aunt) Rosing. Her house was nearby but she lived and ate with us as my mother – also a house help in England – paid her monthly. When Manang Rosing was no longer with us, we asked our cousin to bring along his entire family to our home so they no longer have to worry about daily expenses. We helped the family with other sources of livelihood like driving a tricycle and helped send their son to school, on top of a salary.

My older cousin, an airline supervisor, has been on a hunt for a relative to take with them to Dubai to care for their toddler. When this offer was passed along to the clan, a handful of our cousins lined up.

It is one thing to be offered to be a house help for a relative who will be able to pay you; it is another thing if that offer comes with an overseas ticket.

Domestic jobs abroad

I know what people like us, perhaps Cosiang too, would put on the line to be a house help overseas. My mother paid a fixer who faked business papers so she could get a tourist visa to the United Kingdom. She bolted and eventually found a way to obtain a working visa while cleaning floors and taking care of children.

When she became a citizen, she got a phone call from a distant relative whose employers in the Middle East were not treating her well. The relative told my mother they were set for a vacation in England soon.

Upon my mother’s advice, our relative snuck out of their London hotel room while her employers slept, and found the nearest payphone where she called my mother to fetch her.

We tell these stories as if they’re just regular anecdotes on job hunting.

We tell these stories proudly because overseas employment has given us a lot. No one in our small town would look at overseas house help and say, “Yaya lang siya (She’s just a nanny).” Everyone would say, “Ang suwerte niya (She’s lucky).”

Knowing these, I cannot imagine how Cosiang’s relatives resolved within themselves the conflict of having a relative in America but not being able to point at anything as basis to say, “She’s lucky.”

Stranger

Throughout the day, I pressed the relatives what they thought was happening with their Aunt Cosiang all those years she wasn’t in touch. Their answers varied, but they were answers that sounded to me like it came from people who didn’t know her.

They simply didn’t know her.

She left when she was 18, when none of them had been born yet.

I didn’t know my mother growing up; I’m still not sure whether I know her now. This is a woman who wrote me letters, who made overseas phone calls, and who came home every few years. But she remained a stranger to me for a very long time.

Imagine someone like Cosiang who did not communicate at all.

A big factor is also that she didn’t send them money. In that way, she wasn’t felt. As bad as it sounds to make it seem that someone is only good for their money, when you can’t have deep personal relations – especially before, when there was no internet yet – what you send home is the next best thing.

Your presence is made felt by the money sent door-to-door, or the balikbayan boxes (care packages) that you await eagerly for a whole week, back when there was no way to track a package. Your presence was felt by the contents of that care package: the imported soaps, lotions, canned goods, and the new clothes which served the double purpose of wrapping fragile items like shot glasses and mirrors.

This was how I came to know the woman I called “Mama.” The Pulidos did not have anything to get to know their Aunt Cosiang.

Norma and Rosita told me they all just settled with the thought that she’s okay in America, never mind the rest of the family in Mayantoc. As long as she was okay.

That is why Tizon’s story hurts them now.

“Masakit din siyempre, nag-iisa lang siya doon, hindi namin nakikita (It hurt us of course because she was the only one there, we didn’t see her),” Norma said.

“Masakit kasi ang tagal-tagal doon, bata pa lang ako noon, ang tagal duon hindi man lang nag-ano ng pamilya dito, hindi man lang nagbibigay (It hurt because she was there for a very long time, yet she wasn’t able to fend for her family here, she didn’t send money),” Rosita said.

Lola Gregoria

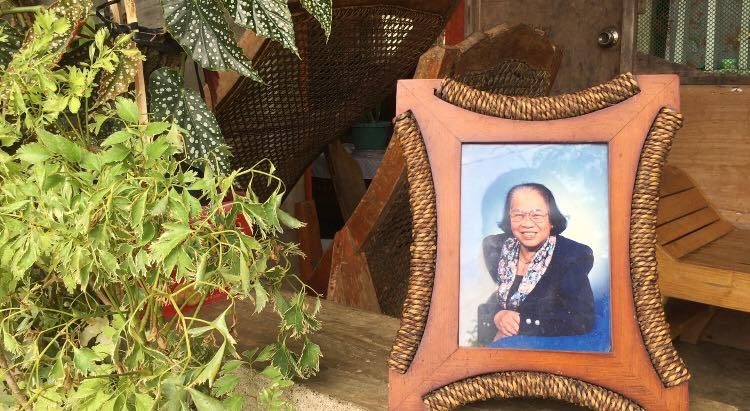

I also met Cosiang’s only living sibling, 99-year-old Gregoria who has 7 living children, one of whom had provided her a big house. She’s strong and lucid for her age, but even she admits she doesn’t remember a lot of things.

She remembers Cosiang as the little sister she took care of, but one who left her when she was old enough to go.

I wanted to ask about Cosiang the teenager, whether Gregoria thinks her sister was the marrying type, whether her sister would have wanted to fall in love and have a family of her own. Whether her sister wanted to be anything else aside from being a maid. Or really, anything at all that she could remember.

All she could tell me is a story she repeated throughout the entire conversation: “Cosiang was so small when I took her because we were both poor. I took her, she grew up with me but when she grew older and she could go with anyone she wanted, and seeing I already had children, she went with them; she left me,” Gregoria said in Ilocano, referring to the Tizons.

Gregoria also kept saying her little sister moved to Manila, and she had to be corrected she moved to America. I spoke to her in my poor Ilocano and asked how she felt to know now that her sister had been a slave, that she wasn’t paid for a long time.

I cannot decide whether her answer is that of acceptance, or that of defeat. “Awan nu awan, anya ngarod (If there was nothing, then there’s nothing. What else can we do)?

It is interesting that even though Cosiang’s relatives say the story hurt them, they didn’t utter a single bad word about the Tizons.

“Thank you kay Alex dahil kahit alam niyang pamilya ang masisira, ginawa pa rin niya ang karapat-rapat mangyari, naibalita pa rin niya kung paano nila trinato noon ang auntie namin,” Rosita said.

(Thanks to Alex because though he knew his own family was on the line, he still did the right thing, he stll told the world how they treated our aunt.)

As Norma said, it matters that Alex stepped up when he did, and that the Tizon children and grandchildren had loved her. It matters that they brought her home 3 times, the final time in 2016, in a tote bag containing her ashes.

“Past is past,” Norma said with a smile.

Past is past too for Gregoria, although her resolve evokes a certain kind of sadness that only a person who’s experienced profound loss would understand.

“Idi natay yen, nagsangit ak, ngem uray agsangit ak, mapagsublim?” she said in Ilocano as she fought back tears that Saturday afternoon.

In English, she meant: “When she died, I cried. But even if I cry would I be able to bring her back?”

Perhaps that’s what makes this story so hard to swallow. That we revere her now, Eudocia, or Cosiang, that she has become an icon of unconditional love and unwavering strength now. That we are saying all these nice things now.

But will that bring her back? – Rappler.com

Note: The writer earlier misspelled ‘Cosiang’ as ‘Kosyang.’ We have corrected this error.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.