SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines — What’s eating up Mindoro’s forests?

The Philippines, under the Aquino administration, implemented a total log ban in 2011 through Executive Order 23, according to Ricardo Calderon, director of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources Forestry Management Bureau (DENR-FMB).

“There’s no logging in Mindoro. There’s a total log ban. We prohibit cutting of trees in natural forests,” Calderon explained. In 1999, Calderon was detailed in Oriental Mindoro; even then, he said he never encountered logging problems.

Some Hanunuo Mangyan, however, disagree.

One of them is Manalo Mayot, the vice-chairperson of PHADAG or the Pinagkausahan Hanunuo sa Dagag Ginuran, a people’s organization for Hanunuo Mangyans. “In fact, illegal logging isn’t destructive, they fear the law. But legal logging is destructive, all have permit,” Mayot said in his local language.

PHADAG blames lowlanders for logging. If there are any guilty Mangyans, they are few and the act is fairly recent, the organization said. It is not in their culture to sell their lumber, they argued,

Calderon rebutted with the claim of zero logging in present-day Mindoro, emphasizing that logging was only rampant in the farther south of Oriental Mindoro in the 1970s when special concessions still existed.

He added that Mindoro’s current problem is charcoal-making despite a provincial resolution banning its transport. For him, this is the reason behind Mindoro’s forest degradation. Calderon clarified, however, that he is not putting the entire blame on the Mangyans.

But some IP rights advocates, like lawyer Jing Corpus of Tebtebba, argue that logging still exists as reported by the IPs themselves. “This happens not just in Mindoro, but also in Sierra Madre, Cordillera, and especially in Mindanao,” she observed.

If there is no logging, then why are trees disappearing? Calderon points his finger at charcoal-making and kaingin (swidden farming), “because when you do charcoal, you do kaingin. You need to clear a forest. The fact that you burned, that’s wrong. See the danger of forest fires.”

But not all kaingin are destructive, advocates say.

Swidden farming, also known as shifting cultivation or rotational farming, is a type of agroforestry system. It is a customary livelihood common across indigenous communities in Asia.

The United Nations Framework on Climate Change (UNFCCC) explained that shifting cultivation among ethnic groups is not a major cause of deforestation in Asia.

Forests

The Philippines has a total forest cover of 6.8 million hectares as of 2010, the DENR-FMB told Rappler.

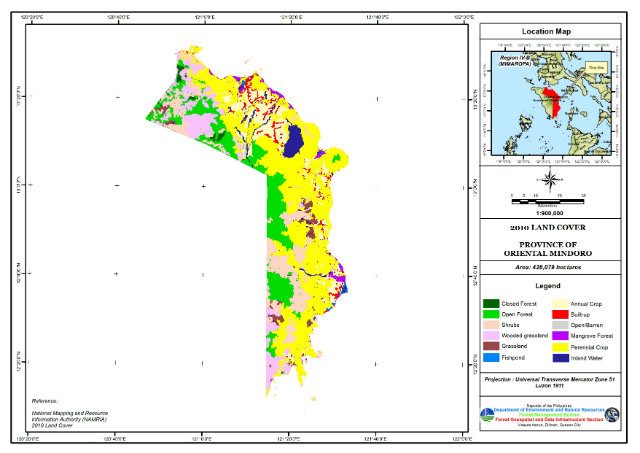

Region 2 has the biggest forest cover, making up 15.27% of the country’s total. Second is Region 4-B or MIMAROPA — home of the Hanunuo Mangyans — at 13.39%.

Mindoro itself, however, had the largest decrease in forest cover area.

|

Percentage of reduction in forest cover area Source: DENR-FMB |

|

| Oriental Mindoro | 61.03% |

| Occidental Mindoro | 53.62% |

Overall, the country’s total forest cover went down by 4.59% from 2003 to 2010. MIMAROPA had the biggest drop among all regions.

In MIMAROPA, other cultivated lands — not forests or wooded land used by man for agriculture or pastures — also showed a “large loss owing to most of it being converted to build-up areas” or those covered by structures like “cities, towns, villages, strip developments along highways, transportation, power, and communication, facilities, and areas occupied by mills, and shopping centers.”

In 2013, the DENR and the German development company GIZ published a study on the “key drivers of deforestation and forest degradation in the Philippines.”

The analysis identified 4 categories:

- Forest products extraction

- Agricultural expansion

- Infrastructure expansion

- Biophysical factors

Under the categories are the following identified key drivers: legal and illegal logging, poaching; charcoal making; fuelwood gathering; non-timber forest products gathering; kaingin making; conversion of forests (fishponds, agroforestry, plantations); grazing; mining; road construction; hydropower dam construction; tourism facilities; climate change, typhoons, flash flood, landslides; and forest fire.

Among all factors, the respondents identified logging, regardless whether legal or illegal, as the top driver of deforestation and degradation. Kaingin placed second.

The results came from selected respondents over certain regions: a mix of representatives from the IP sector, the DENR, local governments, people’s organizations, traders, the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples, the Philippine Council for Sustainable Development, and civil society organizations.

Among IP respondents, they did not identify kaingin as a major driver, but tagged logging and mining as the main culprits.

|

List of direct drivers of deforestation and forest degradation identified |

|

| Legal and Illegal Logging, Poaching | 40.58% |

| Kaingin making | 16.98% |

| Climate change, typhoons, flash flood, landslides | 12.73% |

| Mining | 8.49% |

| Charcoal making | 8.15% |

The study also identified “indirect drivers” such as weak institutional capacities and law enforcement, corruption and political interference, irresponsible attitudes, high demand for wood, and limited livelihood options. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.