SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – When marine biologist Margie Dela Cruz saw an old man about to plant mangrove seedlings in a channel in Guiuan, Eastern Samar, she panicked.

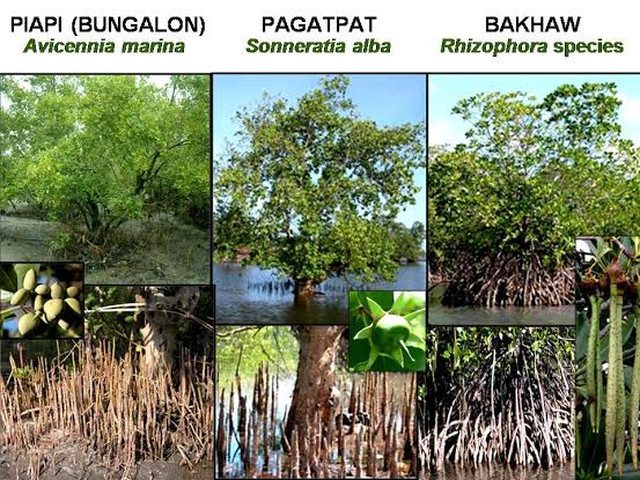

The man was about to plant a species of mangroves called Rhizophora, more commonly called bakhaw, in seagrass beds, a completely different ecosystem from mangroves and home to a different set of organisms.

Bakhaw do not naturally grow in the channel in the fishing village of Namitan. Instead, pagatpat (Sonneratia alba) and piapi (Avicennia marina) mangroves thrive there.

By planting mangroves that had never been there, the reforestation only replaced one valuable habitat with another less viable one.

Dela Cruz clearly remembered what the old man replied to her panicked questioning: “Sa gobyerno naman ‘yan. Bakit sila magtuturo ng mali? (This is a government project, Why will they teach us the wrong thing?)”

But that is exactly what may be the case, according to several Filipino scientists.

Many have called the Department of Environment and Natural Resources-led program “unscientific” and “rushed.”

One mangrove species is favored, ignoring the suitability of the species for different sites. Mangroves are replanted in inappropriate areas – like seagrass beds, mudflats, and rocky shores.

The result, they said, is often wasted public funds since the mangrove seedlings die.

Chief among the voices calling for a rethinking of the program is world-renowned mangrove scientist Jurgenne Primavera, who was named a TIME Magazine Hero of the Environment in 2008.

“Stop the non-science planting on old coral beds, seagrass, and mudflats,” she told Rappler in a phone interview.

Mudflats, she said, are where aquatic birds feed during low-tide. Seagrass beds are feeding grounds and nurseries for marine turtles, seahorses, dugong, coastal fish, and shellfish. They also buffer waves and improve water quality.

Even in successful cases “bakhaw plantings on seagrass beds are one ecosystem’s gain and another’s loss,” she said.

‘Convenient’ planting

If the allegations are true, the government’s reforestation strategy may be wasting millions of taxpayers’ money and giving a false sense of security to communities depending on the mangroves for protection against high waves and storm surge.

In press releases, the DENR said the government had allotted P1 billion for the “massive reforestation of mangrove and beach forest across the country.”

Of this, a sizable chunk will go to Yolanda-affected Eastern Visayas. This is on top of the P38 million for mangrove and beach forest planting in Leyte and Samar.

Mangrove reforestation is also getting funds from the trillion-peso National Greening Program (NGP), the government’s biggest reforestation program that aims to plant 1.5 billion trees by 2016.

There are several facets of the reforestation strategy that could spell disaster, said Primavera.

For one, the choice of bakhaw for planting in many sites.

A government employee who wished to remain anonymous told Rappler that while there is no “straightforward rule” to plant only bakhaw, it’s the popular choice because of its convenience.

Bakhaw propagules are easy to plant, not requiring a 3- to 6-month nursery phase like piapi and pagatpat. Its propagules, around 60 to 80 centimeters in length, are also large and thus more visible.

They grow into the image of mangroves most Filipinos are familiar with – large, pipe-like roots forming arches above the water.

But while the bakhaw’s glorious roots make it appear sturdy, it is in fact not suited as a frontliner mangrove.

“[Bakhaw roots] cannot withstand strong wave or wind action. They either hide behind pagatpat or piapi or line inner tidal rivers and creeks,” said Primavera.

No wonder then that fishermen in Tacloban have reported dead bakhaw mangroves to Primavera.

Dela Cruz also mourned a P500,000-mangrove replanting project in Hernani, Eastern Samar, where bakhaw seedlings did not grow because they couldn’t withstand the impact of high waves.

Bakhaw mangroves are thus unlikely to perform the task they were planted for: to withstand storm surges and high waves in the event of a typhoon.

Even if they reach maturity, they might end up giving only a false sense of security to Yolanda coastal communities.

No survival rates

DENR Forest Management Bureau Director Ricardo Calderon confirmed there is no department rule to plant only bakhaw.

“We are investing on on-site assessment to determine what is appropriate planting material on a per area basis,” he told Rappler.

He said field personnel are instructed against planting in seagrass beds and coral reefs but he admitted they “usually” plant in mudflats.

Though he welcomes the input of scientists, “field condition dictates what the planting material should be.”

He said field personnel consult two manuals when leading reforestation efforts – The Philippines Recommends for mangrove production and harvesting by the Philippine Council for Agriculture, Forestry and Natural Resources and Research Development (PCARRD) and the Ecosystems Research and Development Bureau’s (ERDB) Manual on Mangrove Reforestation.

But Calderon added, there are “site-specific conditions that aren’t found in the textbook.”

What worries scientists even more is the lack of reporting on survival rates of the mangroves.

The NGP’s website only reports the number of seedlings planted and the size of the area planted with seedlings.

Survival rates, however, would indicate if the seedlings have a strong chance of reaching maturity and of thus providing the ecological benefits they were planted for.

If the bakhaw seedlings in Guiuan were to die in a few months, would that reflect on the NGP’s accomplishment report?

Money in trees

The millions of pesos funneled into mangrove reforestation may be doing more harm than good, argued Primavera.

Most of the budget supposedly goes to buying seedlings and paying locals or NGOs to plant and maintain the seedlings.

The large funds looming over the project could explain reports of over-estimation of mangrove damage. (READ: Bulacan forest fires part of reforestation scam?)

The DENR had claimed 1,700 hectares of damaged mangroves in Samar and Leyte. But Primavera and other scientists, after surveying the same sites in January and March 2014, found the damage spanned only 100 to 200 hectares.

“What we found out was they are not totally damaged. They only looked dead because they had no leaves,” said Primavera.

After an oil spill in Cordova, Cebu, the DENR said 328 hectares of mangroves had died even if UP Visayas scientists had found only half a hectare of damaged mangroves.

Bloating such figures, Primavera said, could be one way to justify bigger budgets.

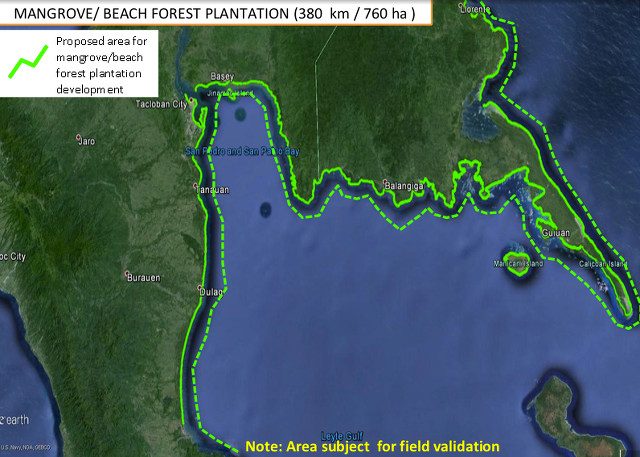

When Environment Secretary Ramon Paje presented to President Benigno Aquino III his department’s plans for Yolanda rehabilitation, he identified large swathes of coastlines for reforestation.

A copy of the November 27 presentation obtained by Rappler shows entire coastlines would be planted with mangroves, even if mangroves had not been there originally.

The reforestation, according to the presentation, would serve as protection against storm surge.

But Primavera argued that there are in fact very few spots suited for mangrove replantation.

Tying up such an ecologically-critical project with large sums of money makes dishonest acts more likely, she suggested. (READ: DENR chief grilled on reforestation program)

Primavera said she had received reports from fishermen of mangrove seedlings being torn out of the soil by the same people who planted them so that “next week there will be new planting and new budget.” (READ: DENR to hire group to audit gov’t reforestation program)

Instead, Primavera promotes the “no pay planting” method where locals, preferably fishermen, who plant the seedlings are given ownership of the mangroves.

The fishermen, by nurturing the mangroves to maturity, would be ensuring their main livelihood’s viability since healthy mangroves mean more abundant oceans.

What pains scientists even more is that, if done right, reforestation need not cost so much because Mother Nature does most of the job.

In Guiuan, for example, “all the natural trees have recovered,” said Dela Cruz.

“Only the very old trees died. But it doesn’t mean you have to replant because there are still saplings and seedlings.”

All natural forests need to regenerate on their own is adequate protection through forest guards and strict laws against land conversion, illegal settlers, tree-cutting, and pollution.

Scientists stand by the notion that, for reforestation as in other things, Mother Nature knows best. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.