SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Geographical knowledge is power. The map – the ultimate form of spatial information – is power.

Maps make us aware of our resources and geophysical dynamics: geology, hydrology, land cover, settlements, transport networks, and other geographical layers. Without cartography there could be no awareness that we have approximately 7,107 islands. Hence, the power to sustainably utilize our archipelagic resources is derived from using maps. One prime example is how cartography and geospatial technologies empowers Project NOAH to to warn people of floods and storm surges for Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (DRRM).

Those dynamics encoded in maps are also employed in laying claim to territory and resource. Do you remember when the UNCLOS panel approved the map of the Philippines’ dominion over Benham Rise? With joy, Filipinos exclaimed, “It’s ours!”

Maps are resources in themselves. Through geospatial technologies such as Geographic Information Systems (GIS), the landscape is altered; that is when licensed professionals do urban planning, architecture, engineering, and military tactics. In any form – printed, folded, posted, flat, 3-dimensional, or projected on screen – maps make geographic knowledge highly utilized.

But there is more to maps than what is in plain sight.

‘Maps lie’

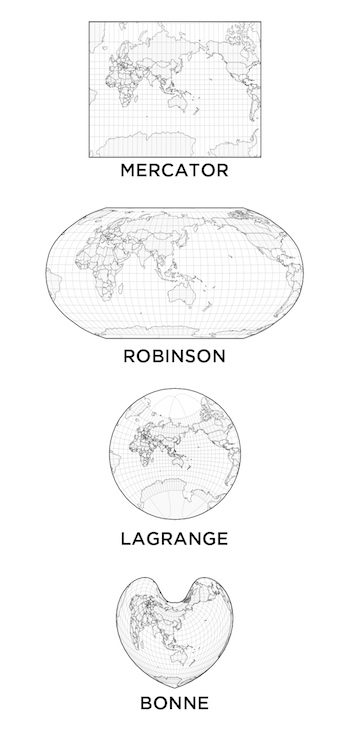

The map – a graphic representation of geographical existence – is always partial. In plain words, maps always lie. Projections, which are definitely required in making flat maps, will always result in distortions. Dr Reina Reyes properly explained this in her article. As the mathematical rendering of the Earth’s 3D surface onto a flat plane, a projection can go from simple to queer, depending on purpose. To the left are examples from the projection machine designed by Mr Jason Davies.

Any map is also vulnerable to other sorts of distortion, e.g. through naming of places. Until the 1990s, the official name of Sasmuan in Pampanga-printed in maps was Sexmoan. It was a mistake done by the colonizers; and replicated by the modern Filipino state afterwards – until Congress finally noticed the “perversion” of the “official” name. Another case is how “South China Sea” or “West Philippine Sea” is applied on the same seascape, depending on the shore where the name is mentioned.

Cognitive maps

The next insight into the transformation of spatial information is in how we remember maps. What counts as map memory – also called a cognitive map – is contingent on who we are. Each of us has intentions, goals, desires, and biases. Through such “handicaps,” we filter and transform the geographic information fed to us.

The mindscape is as important as the landscape.

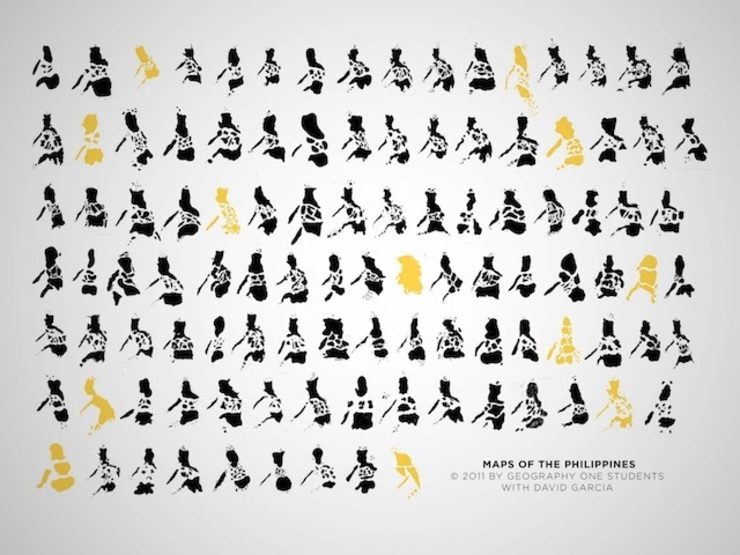

I tried to test the claim through simple crowd sourcing with my previous geography students in UP Diliman. Towards the semester’s end, I asked each student to draw a mental map of the Philippines on an A4-sized paper. Afterwards, we juxtaposed their work.

Note the difference across the personal works. The differences between the cognitive maps were dependent on factors such as:

- Level of learning

- Perception of distance and area

- The extent of their personal travels

These students were provided with the same learning materials throughout the semester, yet for the same 7,107 islands, the mind maps varied greatly.

Do maps matter?

“It’s just a map!” Does it really matter?

Definitely. Such transformation of spatial data is always enforced and reproduced by power relations. Power, such as those exuded by political institutions, is ever present in the mapmaking process. The town councils, courts, and DENR certify cadastral maps of lots, towns, and provinces. Congress has the power to create provinces and the boundaries thereof. UNCLOS is mandated to settle territorial squabbles.

This phenomenon became apparent when institutions step in as neighbors fought over land titles; when Makati and Taguig defended their cases and tax maps on the BGC issue; and when the Philippine map and claim on Benham Rise needed the UN stamp. Through maps, power is made visible and graphical.

In addition, powerful groups can do intentional errors and omissions in maps. Prior to its public release, Global Positioning System (GPS) was a top tool of the US military for decades. When the system was opened for public use, the armed forces deliberately included an error of a few meters in the location readings of any GPS unit; it was a handicap for those who wanted to precisely locate US military assets. Militaries engage in similar projects by having their bases blurred or patched in Google Earth. Similarly, in Google Earth it is not rare to see clouds that cover open-pit mining sites in the Philippines. In maps, what is hidden is as important as what is shown.

Through power dynamics, maps become the geographical fact and “truth” – even geographical coordinates can be manipulated. “The essence of technology,” Martin Heidegger admonished, “is by no means anything technical.”

Maps and geopolitics

Look at geopolitics. Observe how China and Russia continue to defy international protocol in the west Pacific and Crimea, respectively. The two nation-states back their claims as they assign ships and tanks as the boundary monuments. Simultaneously, their state cartographers do their propaganda work as the “might is right” doctrine is being practiced.

There is no history of cartography without a history of conquest.

When we read maps with such critical lens, we shall see that there is a Game of Thrones expressed in the maps. In his journey to The Wall, Tyrion Lannister knew it best when he said “that the map was one thing and the land quite another.”

The public imagination of national identity is anchored in the interaction of power relations and spatial information. Are the Tausugs Filipinos? You don’t have to interview each Tausug and visit their territories before saying that they are part of the Philippines. In our formative years, we just had to take it for granted that every resident in the 7,107 islands in the high school map exam is part of the nation; otherwise, we would have obtained bad grades.

Therefore, when you visit finally their territory, some Tausug members may tell you that they are not Filipinos. Some might even reply to you with a sense of conviction: “Hindi ako Pilipino; Tagalog iyon. Tau-sug ako (I am not a Filipino; that is a Tagalog. Instead, I am Tausug).” The imagination, belief, and feeling of nationalism may not be mutual.

Hence, the State employs the education system, media, and other channels to create the necessary mental map to accomplish the project of nation building. The visual representation is repeated, as the medium becomes the message. The “ours, theirs, us, and them” is thereafter made real through the archipelagic map in stamps, shirts, money, classroom walls, and the logo we use to announce that it is more fun in the Philippines. Therefore, we have to be aware that, as with the case of the “national” language, mapping is likewise a social construction project.

“The map is the perfect symbol of the State,” said Mark Monmonier.

‘Power is knowledge’

Thus far, we have tried to argue that power and knowledge are intertwined in geography and cartography. The argument can now shift from the popular dictum of “knowledge is power” to the admonition given by Michel Foucault: “power is knowledge.”

How could such esoteric matters be employed? Taking a critical stance in reading maps protects us from misinformation. Furthermore, in using the stance there can be opportunities in doing a “counter-mapping” of our own while avoiding the mistakes of those who misused geographic knowledge. This is way better than reducing geography to merely having the country capitals and mountain names memorized.

This is our critical stance: in maps, power becomes geographical “truth.” Power is spatial. – Rappler.com

David Garcia is a geographer and licensed urban planner on mission for the United Nations. Guiuan, Eastern Samar, his current duty station, was where Super Typhoon Haiyan (Yolanda) first made landfall. His duty in Guiuan is to expedite mapping, policy-making, planning, and project management for the recovery, rehabilitation, and reconstruction of the town.

Prior to his UN mission, he was a faculty member of the University of the Philippines in Diliman.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.