SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

He came from a migrant family. He lived in a largely Catholic country with millions in poverty. He struggled under a dictatorship. Eventually, he led a local church denounced by critics for meddling in politics.

His name is Jorge Mario Bergoglio. Now known as Pope Francis, he is the Italian-blooded Latin American whom Filipinos call Lolo Kiko – “lolo,” the local word for grandfather, and “Kiko,” a nickname for Filipinos named Francisco.

From January 15 to 19, the 78-year-old Lolo Kiko visits the kind of country close to his heart.

This Philippines, after all, has more than 10 million nationals working abroad. It is also mostly Catholic, with more than half the population considered poor. It knows the pains of living under a dictator. It is home, as well, to a local church that often clashes with the government.

Who is Pope Francis in the eyes of the Filipino?

Son of migrants

Lolo Kiko: Pope Francis in the eyes of the Filipino

Exactly 86 years before the Pope flies to the Philippines, his family ended a life-changing voyage by sea – eventually producing the first Pope who, in his own words, came “from the ends of the earth.”

It was January 1929. The Bergoglios arrived in Buenos Aires, Argentina, after fleeing the fascist regime of Benito Mussolini in Italy.

The Bergoglios came from Portacomaro village in an Italian region called Piedmont, a name based on medieval Latin words that mean, “at the foot of the mountains.”

In his biography, El Jesuita (The Jesuit), the Pope described the Bergoglios as neither rich nor poor. In fact his grandparents owned a café. Still, the elder Bergoglios “wanted to go to Argentina in order to be near their siblings,” who had lived there since 1922.

The Bergoglios had another, more pressing reason to leave Italy: “the advent of fascism,” according to the Pope’s sister, Maria Elena, in an interview quoted by La Stampa.

Their grandmother, Rosa, strongly rejected fascism. Maria Elena told Italian journalist Andrea Tornielli: “Grandmother Rosa was a heroine for us, a very brave lady. I’ll never forget when she told us how in her town, in Italy, she took the pulpit in church to condemn the dictatorship, Mussolini, fascism.”

In contrast, Argentina “held the promise of seemingly untold job opportunities, better pay, the chance of an education for all, and considerable social mobility….a land of peace and progress,” authors Sergio Rubin and Francesca Ambrogetti wrote in El Jesuita.

Political and economic turmoil loomed in Argentina, however. The Great Depression damaged the country’s economy, and its military launched a coup in 1930.

Against this backdrop, Jorge Mario Bergoglio – born on December 17, 1936 – grew up in a family of 5 children. His father, Mario, worked as an accountant in a railway company, while his mother, Regina Savori, stayed home to raise the Pope and his siblings.

In an interview quoted by author Paul Vallely, the Pope said the Bergoglios “had nothing to spare, no car, and didn’t go away on holiday over the summer…but still never wanted for anything.”

Like the Pope’s family, around 2.97 million Italians migrated to Argentina for various reasons from 1857 to 1940 alone. Italians made up around two-fifths of the immigrants to Argentina during this period.

At around the same time, thousands of Filipinos also began to leave the Philippines for a better life abroad. More than 100,000 Filipinos fled to the United States, mostly in Hawaii, from 1906 to 1934, according to the Center for Migrant Advocacy. The Filipinos in Hawaii mostly worked as plantation workers and farmers, as the Philippines remained an American colony.

The Philippine government, as of 2012, pegs the number of overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) at 10.49 million.

The president of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP), Lingayen-Dagupan Archbishop Socrates Villegas, said the plight of migrant workers “brings Pope Francis close to Filipinos.”

The Bergoglios “know the meaning of being separated from the family, being uprooted from your own country, in order to seek greener pastures,” Villegas told Rappler. “That’s really very Filipino, right? Our OFW culture is really in the Bergoglio line.”

Eight decades after his family fled Italy, OFWs can take comfort in the words of the first Latin American pontiff, who considers the care for migrants a hallmark of his papacy.

“Migrants and refugees are not pawns on the chessboard of humanity,” Francis said in a message in 2013. “Dear migrants and refugees! Never lose the hope that you too are facing a more secure future, that on your journey you will encounter an outstretched hand, and that you can experience fraternal solidarity and the warmth of friendship!”

Devotee: Man of popular piety

Lolo Kiko: Pope Francis in the eyes of the Filipino

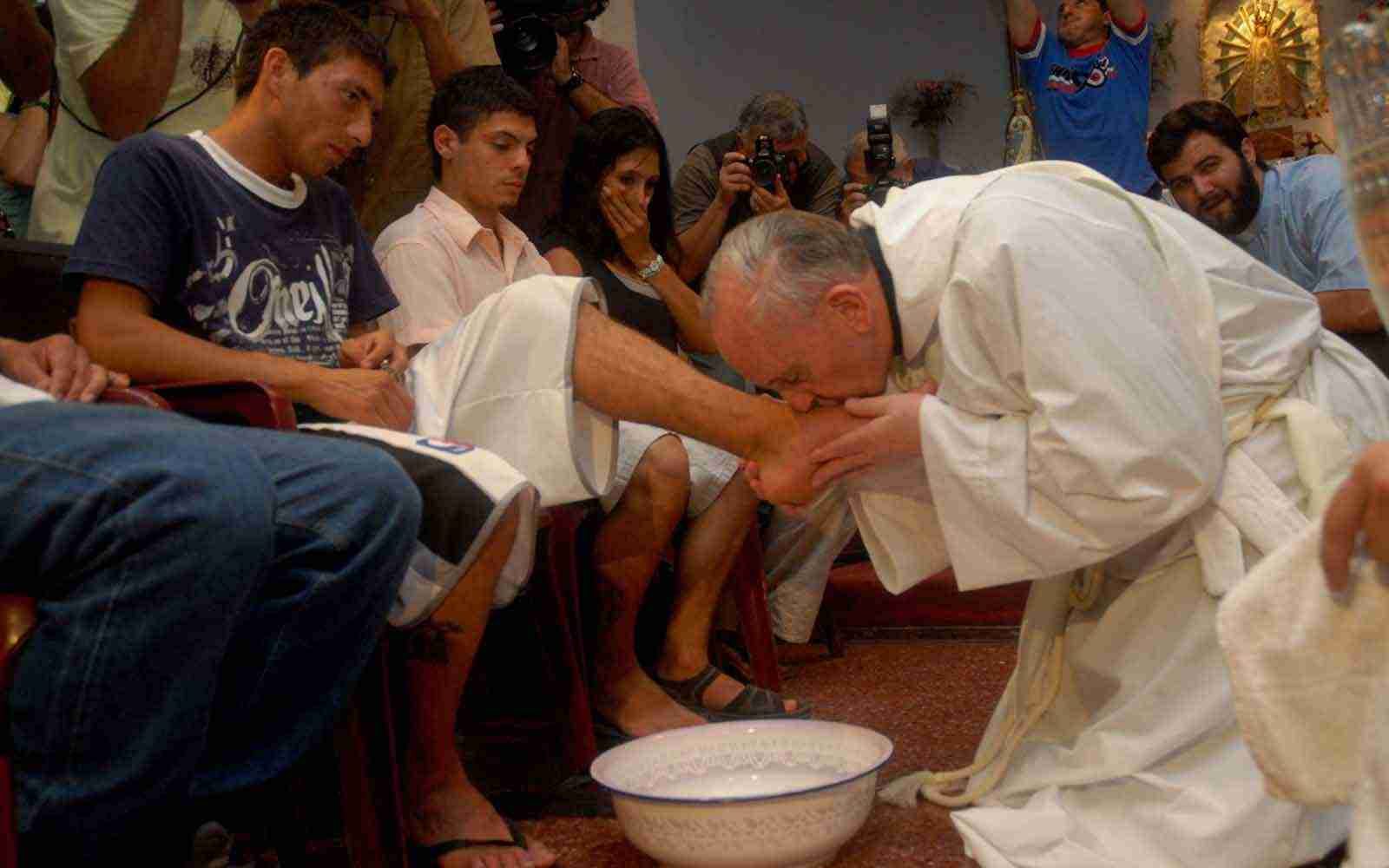

In Rome a decade ago, a man in his 60s entered a Franciscan church at exactly 9 am every day. He always approached the statue of Therese of the Child Jesus, a saint with a huge number of devotees in the Philippines, to whose intercession the man attributed many answered prayers.

The man intrigued the Franciscans because of one of his habits.

“At the end of the prayer, he used to do as many old ladies – who are sometimes looked down upon in this country – do. He touched the statue and kissed it,” the Franciscans posted on their webpage soon after Francis became Pope, according to author Paul Vallely, who wrote a book about Francis.

Then, one day, the Franciscans noticed the man wearing a bishop’s cassock. (Photos suggest he walked the streets of Rome in a coat that concealed his clerical garb.) Who would have thought it was Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, then the archbishop of Buenos Aires, on his way to meetings at the Vatican?

Many Catholics, after all, scoff at the things he did. Kissing and touching statues, praying the rosary, or joining processions – as Filipinos do – form part of popular piety, an expression of faith that is culture-based. Critical theologians reject popular piety as an ignorant set of practices, but that is not so for the Pope from Buenos Aires.

“He is a man of popular piety,” said Fr Francisco de Roux, head of the Jesuits in Colombia, as quoted in Vallely’s book, Pope Francis: Untying the Knots.

“He captures the experience of God in the simplicity of popular practices, processions, shrines, the Christmas novena, the family saying the rosary. To him the strength of Catholicism is in the way simple people live their faith,” De Roux said.

Francis learned this faith from the woman who “had the greatest influence” in his life: Rosa Bergoglio, whom the Latin American Pope called Nonna Rosa – nonna, the Italian word for grandmother.

Pope said in a radio interview that Nonna Rosa, a member of the group Catholic Action, “taught me a lot about faith and told me stories about the saints.”

Nonna Rosa influenced him so strongly that, if the Pope were to flee a burning house, he “would be truly sorry to lose” only two things, he said in El Jesuita. First is his agenda, which “contains all of my appointments, addresses, telephone numbers.” Second is his breviary, a Catholic book of prayers, within which he keeps his grandmother’s creed.

Nonna Rosa’s creed reflects a devotion to Mary, the mother of Jesus: “May these, my grandchildren, to whom I gave the best my heart has to offer, lead long and happy lives, but if one day hardship, illness, or the loss of a loved one should fill them with grief, may they remember that one sigh directed to the tabernacle, home to the greatest and most august martyr, and a glance toward Mary at the foot of the cross, may cause a soothing drop to fall on the deepest and most painful of wounds.

Francis brought Nonna Rosa’s faith when he became a Jesuit priest on December 13, 1969.

Argentine priest Fr Luciano Felloni, who knew Francis as a priest in the early 1990s, told Rappler that the Pope’s emphasis on popular devotions makes him comparable to Filipinos. Felloni said Filipinos might be surprised to see a pope touching or kissing the image of Mary, for instance, as many in the Philippines do.

Felloni, for example, recounted Francis carrying “like a baby” the 15-inch statue of Our Lady of Aparecida, whom the pontiff called “the Mother of Every Brazilian.” He said previous popes wouldn’t have done the same thing, as they “have other forms of devotion.”

“That’s a very Latino form of expression. And that makes us, Filipinos and Latin Americans, similar,” the priest said in Filipino.

The Pope will see this form of expression, at one of its highest points, when he visits the Philippines. January 18, when the Pope presides over a Mass at Rizal Park, is the Feast of the Santo Niño or the Sinulog Festival in Cebu. At the Rizal Park on that day, Catholics will bring statues of the Santo Niño, a popular image of the Child Jesus in the Philippines, to usher in the Pope.

Francis, after all, believes in the “evangelizing power of popular piety.”

Quoting a key document by Latin American bishops in 2007, Francis calls popular piety “a spirituality incarnated in the culture of the lowly.” He said, “Let us not stifle or presume to control this missionary power!”

Dictator’s sympathizer?

Lolo Kiko: Pope Francis in the eyes of the Filipino

A day before cardinals elected John Paul II’s successor in 2005, a newspaper article circulated against then Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio. The Pope’s biography, El Jesuita, said the story “was e-mailed to the voting cardinals with the aim of jeopardizing the Argentine cardinal’s chances.”

The article said Bergoglio “was partly responsible for the 1976 kidnapping of two Jesuit priests” who worked in a slum district during the Argentine dictatorship.

Bergoglio repeatedly denied this claim. He said he even worked to free the Jesuit priests, and offered refuge to the military junta’s other critics.

The story began with the arrest of two Jesuits, Orlando Yorio and Francisco Jalics, along with thousands of activists. The junta in Argentina, which ruled from 1976 to 1981, apparently viewed the priests’ social work as a threat.

Seen by critics as the junta’s sympathizer, Bergoglio allegedly requested Yorio and Jalics to stop their work in the slums. The priests refused, so Bergoglio “informed the military that the priests were no longer under the Church’s protection, thereby leaving the way clear for their kidnapping, and thus putting their lives at risk,” El Jesuita quoted the anti-Bergoglio article as saying.

Bergoglio, for his part, said he in fact worked to free Yorio and Jalics.

One day, Bergoglio said, he even convinced the military chaplain to call in sick, so that he can celebrate Mass with commander-in-chief Lieutenant General Jorge Rafaél Videla and his family. After the Mass, he spoke with Videla “with the intention of finding out where the arrested priests were being held.”

Bergoglio said his efforts led to the freeing of Yorio and Jalics “because they could not be accused of anything and, second, because we wasted no time.” He added: “The very night I learned they had been kidnapped, I set the ball rolling.”

In March 2013, Jalics himself said he initially thought Bergoglio reported them to the military, but “it became clear to me after numerous conversations that this assumption was baseless.” (Yorio is dead.)

In El Jesuita, Bergoglio also claimed he “hid some people” hunted by the military. He sheltered them in the Jesuit seminary in the guise of “20-day retreats,” he said. Once, he also allowed a man who looked like him to use his identity – from his ID to his clerical clothing – to escape Buenos Aires and go to Brazil. “In that way,” Bergoglio said, “I managed to save his life.”

Unlike the people Bergoglio reportedly saved, however, up to 30,000 of the junta’s suspected opponents died during the Argentine dictatorship. Of this number, around 20,000 were reported to have “disappeared” – called “ desaparecidos” in the Philippines.

The same thing happened in the Philippines under the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos, who implemented martial law from 1972 to 1981. Nearly 50,000 Filipinos claimed to have been human rights abuses during martial law. Thousands sought refuge in parishes. Since that period, more than 1,800 Filipinos have become desaparecidos.

Decades later, the Pope’s words resound for countries like the Philippines and Argentina which underwent military rule.

He said in El Jesuita: “I believe we must devote ourselves to a culture of cooperation, or we are lost. The totalitarian approaches of the last century – fascism, Nazism, communism, and liberalism – lead to fragmentation. They are collective approaches masked as unification, principles without organization. The most human of challenges is organization.”

Voice of the poor

Lolo Kiko: Pope Francis in the eyes of the Filipino

In a festive mood, Argentina’s president entered the Buenos Aires Cathedral on May 25, 2004, to join the Te Deum, a thanksgiving prayer led by Archbishop Jorge Mario Bergoglio for one of Argentina’s national days.

Argentine President Néstor Kirchner didn’t see it coming. In his face, Bergoglio lashed out at Kirchner’s government. The archbishop slammed “those who feel so included they exclude everyone else, those who are clairvoyant they have become blind,” according to El Jesuita. He also said “copying the hate and violence of the tyrant and the murderer is the best way to inherit it.”

El Jesuita described the Te Deum of 2004 as “having the largest political consequences” for Bergoglio.

Aghast, Kirchner vowed never to attend Bergoglio’s Te Deum again. Kirchner and his wife, Cristina – who succeeded him, in what critics call a political dynasty – snubbed this event each year. That was, until Bergoglio became Pope and Mrs Kirchner attended the Te Deum again on May 25, 2014.

The Te Deum incident showed Bergoglio in the mold of Filipino bishops like the late Manila Archbishop Jaime Cardinal Sin, who helped overthrow the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

Bergoglio, who became archbishop on February 28, 1998, attacked the government when he had to. He slammed the government, for one, over “the unjust distribution of goods” as well as laws on same-sex marriage and divorce.

He also spoke out when Argentina faced an economic crisis in 2001 and said it “would refuse to pay the $94 billion it owed to foreign banks and investors,” author Paul Vallely wrote in the biography, Pope Francis: Untying the Knots.

Vallely said the Pope attacked how the debt-restructuring process meant “the cutting of services on which the poor depended.”

Bergoglio said “the ‘unjust distribution of goods’ creates a ‘situation of social sin that cries out to heaven and limits the possibilities of a fuller life for so many of our brothers.”

He, too, denounced human trafficking in Argentina, a global scourge that also affects the Philippines.

In a Mass for victims of human trafficking in Buenos Aires, the former archbishop said: “To you, trafficker, today we say this: Why do such things? You are bringing yourself nothing; only hands heavy with blood from the evil that you have done….Where is your brother, trafficker? He is your brother! He is your flesh!”

To fight these problems, he stressed the government’s need to provide the poor with work.

Like in the Philippines, unemployment is one of Argentina’s biggest problems. In August, the unemployment rate in Argentina “rose to 7.5%” as companies reduced workers due to the country’s recession, the Wall Street Journal reported.

The Philippines had an unemployment rate of 6.7% roughly during the same period.

In El Jesuita, Bergoglio said government should provide jobs because “work anoints a person with dignity.” “Dignity is not conferred by one’s ancestry, family life, or education. Dignity as such comes solely from work.”

He said: “What happens is that the unemployed, in their hours of solitude, feel miserable because they are not ‘earning their living.’ That’s why it’s very important that governments of all countries, through the relevant ministries and departments, cultivate a culture of work, not of charity.”

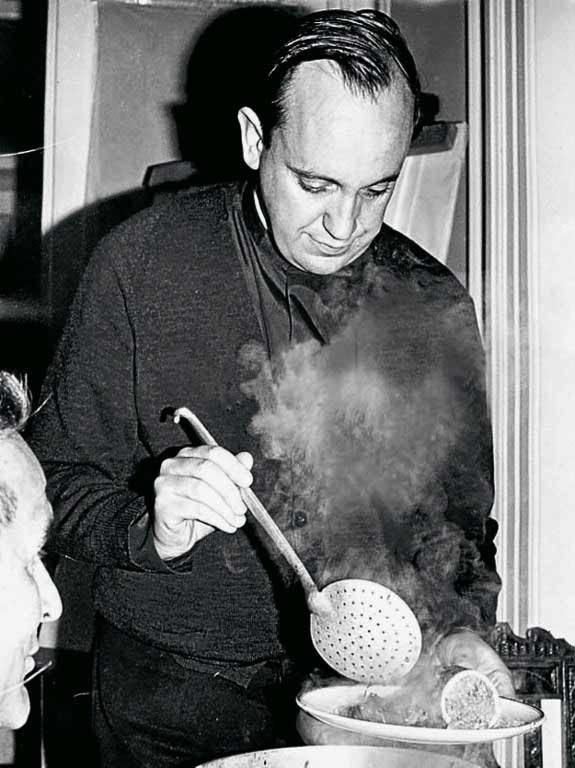

More than anything else, Bergoglio identified with the poor by trying to live like them. The Buenos Aires archbishop, for one, stayed in an apartment and cooked his own meals. He also frequented the slums, “talking with people, drinking tea, and eating biscuits in the villa’s homes, posting for photographs when requested,” Vallely recounted.

“My people are poor and I am one of them,” said the archbishop known by the poor as El Chabon (The Dude).

He continued his simple lifestyle when he became Pope on March 13, 2013.

At the Vatican, Francis lives in a modest guesthouse, not the Apostolic Palace. Occasionally, he also sits at the back of the guesthouse chapel and carries his own luggage.

His example sends a strong message to the Catholic Church around the world, including the Philippines, which has seen many priests abusing their privileges.

The president of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of the Philippines (CBCP), Lingayen-Dagupan Archbishop Socrates Villegas, warned these priests two weeks before the Pope’s trip to the Philippines: “It is a scandal for a priest to die a rich man.”

People’s Pope

Lolo Kiko: Pope Francis in the eyes of the Filipino

When Pope Francis visits the Philippines in January, he will see a country not only with the same traits as his country of birth.

He will also see a Catholic Church facing the same challenges. One of this is the loss of interest among the Church’s members, many of whom have chosen to move to other religious groups.

Fr Luciano Felloni, an Argentine priest who has lived in the Philippines for 20 years, said the problem boils down to the Church’s need to reach out to its members.

The Catholic Church in Argentina, for one, is suffering dwindling membership, from 95% of the population in 1950 to 71% in 2014, according to Pew Research Center.

While data on the Philippine Catholic Church is scarce, the available statistics also point to a downward trend. In 1990, government statistics showed that 82.92% of Filipinos identified themselves as Catholic. In 2010, the percentage of Catholics went down to 80.58%.

A survey by the Social Weather Stations in 2013 showed that 9% of Filipinos sometimes think of leaving the Catholic Church.

Speaking to Rappler, Felloni said in Filipino: “The priest cannot always stay in the parish. We need to see him in the areas he covers, the chapels, the streets, going to people….The presence of the Church outside is important.”

Felloni echoes the call of Francis in his landmark document, Evangelii Gaudium (The Joy of the Gospel): to reach out to the world’s peripheries.

From his native Argentina, the People’s Pope brings these lessons to the Philippines as Lolo Kiko, a man close to the Filipino heart.

In the Philippines, Lolo Kiko – the son of migrants, the devotee, the man who struggled under a dictator, the voice of the poor – is set to meet disaster survivors among Filipinos.

Not only is he visiting Leyte, the main objective of his trip, to meet Super Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) and earthquake survivors in the Visayas. He is also seeing families, young people, and priests who, in the words of Manila Archbishop Luis Antonio Cardinal Tagle, “have experienced other forms of disasters in life.”

The Pope explained in El Jesuita: “If the Church limits itself to the work in its parish and lives shut up in its community, then the same thing will happen to it that happens to a person who shuts himself in: it will atrophy, physically and mentally. Or it will deteriorate like the inside of a locked room, mold and damp spreading everywhere.”

He added: “It’s true that if you venture out onto the street, the same thing could happen to you as could happen to anyone: you could have an accident. But I prefer an injured Church to a sick Church a thousand times over.” – Rappler.com

Photo research courtesy of LeAnne Jazul. Main photo in Introduction courtesy of AFP.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.