SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Ferdinand Marcos was partial to athletes who have ‘a danger’ about them.

If a book were the sole indicator of a person’s character, then Mark Kram is no doubt the ballsiest sportswriter of all time. His Ghosts of Manila turns the Muhammad Ali narrative upside down so thoroughly that readers used to equating the boxer to anything less than a sublime figure will wince at every turn of the page.

It’s a rabbit hole for Ali fans, that’s for sure.

But because the book isn’t just about Ali-Joe Frazier Part 3 but also about Manila in the ’70s, it steps into another bizarro world — the Philippines at the peak of military rule. Kram devotes eight, maybe 10 pages of content in total describing what he calls “land of palabas, dramatic spectacle,” which is the perfect place to host a show as attention-grabbing as a heavyweight title fight.

“Manila did not provide the usual backlighting of film noir, endemic to boxing but for a long time hardly evident,” Kram wrote. “Instead, the city, sagging under the weight of millions from the provinces, threw up the feel of tropic gothic, a place . . . that ‘held you as a smell does.’ “

Kram was unflinching in his depiction of the country and its ruler, Ferdinand Marcos, who granted the Sports Illustrated writer an unfettered day-in-a-life access hoping foreign press people such as Kram would spread the word throughout the world that the Philippines was, as Kram notes, under “Martial law with a smile.” Kram tagged along with Marcos in one of his golf games, during which they engaged in an awkward one-on-one and touched on Marcos’s pick in the Ali-Frazier fight.

“Marcos had a high opinion of himself as a sportsman and a man of fitness, and at age fifty-six considered himself the most athletic head of state in the world. An aide later boasted of it, too, so I asked him if I could watch him go through his routine. No problem, and two days later, standing around like a court idiot, I attended a Marcos workout, wishing that I had kept my mouth shut. ‘I make my decisions early in the morning,’ he said, ‘while jogging in place in the bedroom.’ He played a fast game of pelota, moving like a jumping coffee bean. He did ten laps in the pool, then, just when I thought he would ask for a game of chess or pick up a piece to demonstrate his famed sharpshooting, he was off to the golf course, trailed by a platoon of aides; several carried automatic rifles, another a holsters and a .45 that belonged to Marcos. There were scattered claps to his reasonably good strokes. He was asked his preference in the fight. ‘Lady Imelda,’ he said, ‘is in love with Ali.’ He laughed: ‘She has a taste for the feminine in men. I’m partial to Frazier. There is a danger about him.’ I remarked on Ali’s reception at the airport. ‘If he was Filipino,’ he said dryly, ‘I’d have to kill him. So popular.’ He then said: ‘That’s a joke now, of course.’ “

The entire occasion must have been surreal for Kram. It’s not everyday that you share a moment on the fairway with a strongman who raises the idea of killing people in jokes-are-half-meant kind of way.

The time when a government agency thought Filipinos didn’t deserve to watch the fight

If you’re a certified history nerd who geeks out at all things bygone, you’ll find this Oct. 2, 1975, account of the fight by the now-defunct Business Today newspaper fascinating, for both the dated references (color TV was a luxury in the ’70s, believe it) and the interesting similarities between now and then (the country grinding to a halt because of boxing).

“Fight fans lined the gates of the Philippine (Araneta) Coliseum as early as 4 a.m. Security precautions were tight as President and Mrs. Marcos arrived minutes before the main event to watch the fight. Elsewhere in Greater Manila, shops were emptied as people trooped to the nearest TV stores to see the ‘thrilla.’ Millions viewed the fight in color in the comforts of their homes, or offices as the case may be. The holiday atmosphere extended even to the stock markets where trading was suspended for almost two hours to allow investors and brokers to view the match.”

I pine for simple times as much as the next person, but not at the expense of living in a world where color TV was optional.

Filipinos were lucky they even got to see match live. Apparently, the government, through the Games and Amusements Board, had planned not to show the fight as it happened. The following is from a report published on Oct. 2, 1975, in the Bulletin Today.

“Earlier in the day, the Chief Executive (Marcos) had ordered the fight covered live by local TV and radio stations through Channels 4 and 7.

“In a complimentary move, the President asked both private and government executives to allow their works ‘time out’ to enable them to watch the spectacle on TV.

“The President, in reversing the decision of GAB Chairman Luis Tabuena not to have the event televised locally, took cognizance of the strong public clamor for a live telecast of the bout.”

If taxpayers were going to shoulder a brunt of the cost of the bout, at the very least, let them see it live.

The Thrilla contract had classic Don King written all over it and that’s never a good thing

A stipulation under the fight contract signed by Don King and the Games and Amusements Board, as published in the Bulletin Today on Oct 1, 1975:

“The Philippine government provided for round trip tickets to Manila for 35 persons from the continental U.S. first class and 30 persons economy class; hotel rooms and three meals per day for 65 persons commencing no earlier than 21 days prior to fight day; 100 ringside and 50 general admission tickets to Don King Promotions people and an unspecified number of television production personnel hired by Don King Promotions.

“On the other hand, the contract calls for the first $5,500,000 proceeds from the sale, lease or exploitation of promotion rights to go to the Don King group and that 15 per cent of the next $5,500,00 of proceeds shall be paid to the government by Don King promotions.

“The Philippines is responsible, under the contract, to supply at its expense ‘television production equipment required to produce a first class international color telecast, including a mobile unit, four color television cameras, a slow motion machine, and two vtr machines: 150,000 watts, three-phase 50 cycles for application to television production equipment; 100,000 watts, three-phase 60 cycles for use of ring lighting; two standby separately powered electrical generators capable of supplying standby power, for the lighting, and production ‘equipment . . .’ ”

This contract is just wrong on so many levels. To say that King, a widely reviled figure in boxing, got the favorable end of this deal is a gross understatement. And there’s the other side to this – why did we agree to such lopsided terms that put us in such glaring disadvantage?

When practice makes perfect . . . business sense

Seeing that a boxing match with the Thrilla’s magnitude would likely never happen again, its organizers did what any businessman with a sound entrepreneurial acumen would do – milk it for all it’s worth.

One of the revenue streams opened up for that event was the workout sessions held at Folk Arts Theater, which welcomed spectators willing to shell out P2, P5 and P10. For point of reference, movie tickets circa late ’70s cost P5.

Is paying to see Ali talk trash for an hour or so and, you know, do some boxing-related things on the side money well spent? If attendance numbers reported in the papers are accurate, the answer is yes.

When Ali opened training camp in Manila on Sept. 16, 1975, the crowd that paid to see him numbered 5,000, according to the Bulletin Today. Five days later on Sept. 21, that swelled to 8,000, which would be a good sized crowd at a PBA game. By the Games and Amusements Board’s estimates, gate receipts at the training sessions held Sept. 14-20, 1975, returned P144,979, the Bulletin Today reported. That’s nearly P4 million in today’s money. No figures for the succeeding sessions were available but, if the trend continued, organizers could have raked in P10 million easy just for two boxers training.

It isn’t rocket science. Anything involving a champion boxer who is a rockstar and circus ringmaster rolled into one is a cash register waiting to go cha-ching.

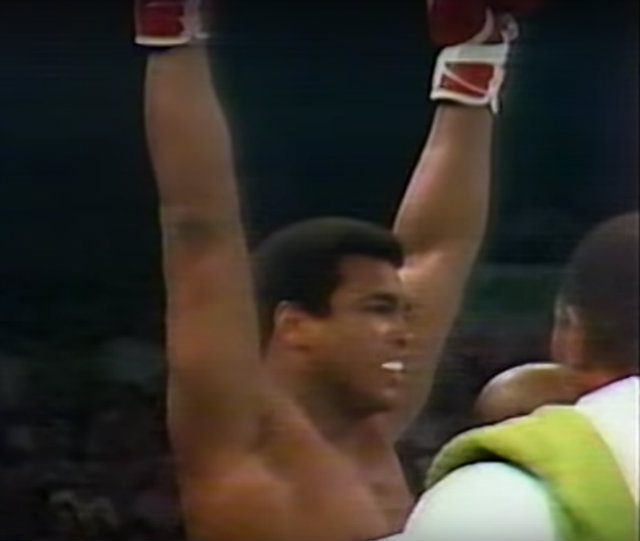

Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier fought a heavyweight title fight in sauna-like conditions

Prizefighting is a vicious way to earn a living. The sport’s essence is to withstand as much physical punishment as you can while you inflict as much, hopefully more, damage on your opponent. In an ideal situation, you hope the only foe you need to face inside the ring is the other guy in gloves and shorts, but prizefighting is the last place you should expect to find ideal circumstances.

In Manila, Ali and Frazier realized they were up against another adversary, unseen but merciless and unrelenting just the same – the stuffy conditions brought about by insufficient ventilation inside the Philippine Coliseum. “Packed tightly and sweating, the crowd of 28,000 seemed to vacuum all the air out of the arena,” noted Mark Kram in his book.

Outside the arena, the temperature was pegged at 31.5 C. Inside, it felt worse. “It was so hot over there,” said Joe Frazier, in an interview with Dr. Ferdie Pacheco on an NBC boxing special commemorating the Thrilla. “The heat was so intensive . . . that I can’t even think anymore. All I know, the fight was there . . . that particular fight, I just couldn’t think. I was there. I just wanted to get the job done.”

Pacheco, Muhammad Ali’s corner physician, said it could’ve been “110 degrees (F),” or 43 C, but Frazier shook his head and cut Pacheco, “No, it was hotter than that.”

Angelo Dundee said in the same NBC TV special that, besides the boxers’ stamina, the oppressive heat affected a crucial gear. “The heat was affecting both fighters. It was murder,” Pacheco said. “It was hot in the building. The heat was a really big play there. In fact, the heat had a big play on the condition of the gloves. They were all water-logged. Soaked.” Bad news because drenched gloves meant they were heavier and, inside them, warmer and sticky.

Jeff Powell, boxing writer for U.K.-based The Daily Mail, likened the atmosphere to being in “a pressure cooker” and believed the temperature was closer to 50 C.

One of Ali’s famous quotes after the fight was he and Frazier left Manila as old men. Given the kind of punishment they subjected each other and the unforgiving environment they fought in, it’s surprising they even left Manila alive.

Frazier’s song for Ali, titled ‘First Round Knockout’ stung champ like a bee

In the realm of theatrics, going toe to toe with Ali was tantamount to public relations suicide. When it came to dropping lyrical bombs, none of his rivals could hold a candle to “the Greatest.”

So Frazier, fully aware he couldn’t win playing Ali’s brand of smack talk, went in another direction – he sang.

During a press conference in Manila, Frazier got behind the mic and performed “First Round Knockout,” a single he recorded with his soul-funk group. The lyrics, which didn’t refer to Ali, were obviously directed at the champ: “He took one look at me, never knew what hit him. Pain on his face tell me, my left hook had caught him. One minute he was so standing tall. The next second he began to fall.”

Because Manila was too small for two heavyweight champions who loved to take swipes at one another, it didn’t take long before Frazier’s musical dig reached Ali’s camp. True to form, Ali sneered at his opponent’s performance. “He’s much worse on stage than in the ring,” Ali said in a report by Bulletin Today published on Sept, 16. 1975. “But he’ll have to learn how to sing because after the fight, he’ll have to look for another occupation.”

The thing is, however, Frazier could carry a tune and it was Ali who couldn’t. “I can’t sing,” the champ conceded a day later, “but I’m more handsome than he is. His nose is crooked.” Score two PR points for Frazier here – the first for one-upping Ali in the musical department and the second for bringing out the sore loser in him. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.