SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Though detractors may argue that the fight scenes in the Rocky movies are over-dramatized and unrealistic, there is no discounting the fact the films have been able to capture the grim reality of a boxer’s life outside the ropes.

There’s a scene in Rocky III, first released 32 years ago, that remains poignant until today for fans of Manny Pacquiao. Dressed in a two-piece suit, Rocky walks into a room to find his trainer Mickey packing up his bags, preparing to take “a permanent vacation.” Mickey, who discovered Rocky in a rundown gym in Philadelphia, saw that his pupil was no longer the desperate warrior willing to do anything to achieve his dreams. Mickey was walking away.

In reality, the trainer of a top fighter wouldn’t dream of doing such a thing. Precious few trainers take home sufficient paychecks from boxing alone, and there’s no shortage of frustration felt by trainers who are unable to sustain their fighters’ hunger.

“Three years ago, you were supernatural. You was hard and nasty. You had this cast iron jaw. But then, the worst thing happened to you that could happen to any fighter. You got civilized.”

The success that fighters work their entire lives to attain is often ultimately their undoing. Marvin Hagler, another boxing legend who made his name in The City of Brotherly Love, once quipped, “It’s hard to get up and do roadwork when you’re wearing silk pajamas.”

For Pacquiao, a man who spent much of his youth sleeping on dirt floors in provincial Mindanao, silk pajamas have been in his wardrobe for a number of years. After 383 rounds in 62 fights over 19 years, the 35-year-old Pacquiao has accomplished feats that will never be duplicated in boxing. He has won world championships in 8 divisions spanning 42 pounds. For Floyd Mayweather Jr to accomplish the same, he’d have to win belts up to 175 pounds, something the 36-year-old isn’t likely to attempt.

At what point is enough enough? When is one-upping your own history no longer satisfying? Manny Pacquiao has probably already passed that point – whether his most ardent supporters want to admit it or not.

Not forever

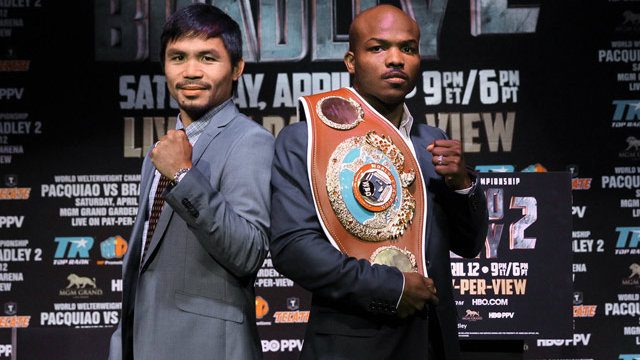

Pacquiao himself admitted as much in the HBO Face Off segment with Timothy Bradley, whom he faces in a rematch of their controversial 2012 fight on April 12 in Las Vegas, Nevada. “I pray that God gave me another fire,” said Pacquiao, after the 30-year-old Bradley questioned his hunger to his face.

The reality is that fighters aren’t meant to fight forever, and once that flame is out, it doesn’t come back. Sure, they can blow on those flames and reenergize enough embers to light their cigarette. A great old fighter is still a great fighter. Just like Muhammad Ali, who at 36, lost the heavyweight title to the much younger Leon Spinks in an upset, only to rededicate himself for one last great performance to regain the title 7 months later and gain vengeance.

Joe Louis also accomplished something similar in 1947 at age 33 when, after being dropped twice and receiving a bogus split-decision win over Jersey Joe Walcott, turned in one final great performance in the rematch, knocking him out in 11 rounds. But these cases aren’t the rule, they’re the exception.

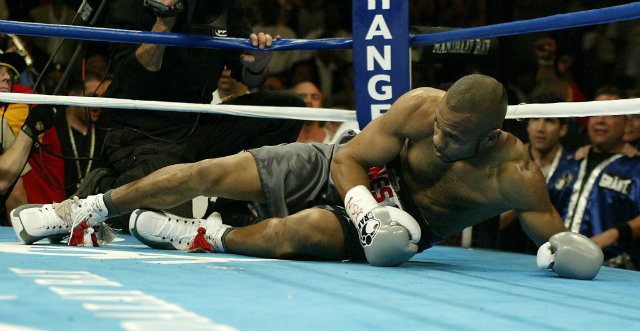

There are more cases like Roy Jones Jr, who, after being knocked out in two rounds in his rematch against Antonio Tarver, looked disinterested in his subsequent fight with Glen Johnson, who knocked him out in 9 rounds. In later fights, Jones could still show off his incredible speed and reflexes, but the fighting heart wasn’t there anymore.

Reawakening

My first taste of witnessing Pacquiao in preparation was prior to the first Timothy Bradley fight in 2012. It was also my first glimpse at the behavior that many had whispered about, but few had spoken about loudly.

This would be the last fight that Pacquiao would prepare for in the mountain resort city of Baguio. There were roadwork sessions missed, friends coming and going from his room past midnight. There were reports that Pacquiao had broken his sparring partner Ruslan Provodnikov’s nose; in actuality Pacquiao had spent significant time on the ropes absorbing right hands from the heavy-punching Siberian, who would go on to win a world title of his own.

Sure, Pacquiao still looked super-human in glimpses, but his movements had slowed down just enough so that the human eye could decipher each step.

Now, you don’t have to be Angelo Dundee to know that the two judges who scored that fight for Bradley were way off base. Though the outcome inspired just as much contrived outrage as it did real, there’s no way Pacquiao lost that fight.

Yet there is something to be said about the effort of Bradley, who despite being hindered by a leg injury earlier in the fight, exhibited the body language of a man who wanted to win more so than Pacquiao. And in Las Vegas, where even the sport’s Golden Boy Oscar de la Hoya once lost a controversial decision to Felix Trinidad because he backpedaled for the final 10 minutes of the fight, that goes a long way.

If the judges needed an excuse to award the fight to Bradley, they had a defensible rationale.

To Pacquiao’s credit, many of those shortcomings in training have disappeared in recent camps. During the Brandon Rios camp in his hometown of General Santos City, Pacquiao looked far more focused and explosive than in previous camps, despite being inactive for nearly a year after being knocked out in 6 rounds by arch nemesis Juan Manuel Marquez. Pacquiao was self-motivated, and by the time trainer Freddie Roach arrived a month into camp to guide the final 6 weeks, Pacquiao was already in shape, both mentally and physically.

Pacquiao has been more diligent in his running, which is an essential component to shaping the mental make-up of a fighter. It’s that feeling of discipline and sacrifice that reinforces a fighter’s confidence. In the one training session I witnessed for the Bradley rematch in GenSan, I can say without exaggeration he looked better than in any other session I had been present at.

Writing on the wall

The writing had been on the wall for a number of years. Pacquiao hasn’t stopped a fighter since 2009, when the referee halted the Miguel Cotto fight two minutes before the final bell. Even in that fight, where he had dropped Cotto twice and battered him into a bloody, swollen pulp of a man, Pacquiao had turned to the referee to spare him from damage.

Against Shane Mosley in 2011 Pacquiao seemed almost apologetic for striking him, touching gloves seemingly after every exchange. Contrast that with his star-making victory over Marco Antonio Barrera in 2003, where Pacquiao battered the aging legend around the ring in one of the most ruthless (legal) exhibitions of recent times.

At no time did Pacquiao suggest to the referee that Barrera had had enough; his beatdown of “The Baby-Faced Assassin” didn’t cease until Barrera’s trainer Rudy Perez stepped onto the apron and entered the ring, embracing Marco with tears in his eyes.

Against Rios last November, Pacquiao showed he was still fast, still smart, and still one of the best fighters in the world. But he also showed that something had changed in him since the last time he had walked up those ring steps. Whereas in the 4th Marquez fight he overextended himself seeking a knockout, Pacquiao begged off a defenseless Rios in the 12th and final round.

Roach reasoned that Pacquiao’s mercy was at play, but Pacquiao himself admitted he was leery of making another costly error like the one that led to his knockout loss the last time he fought in Las Vegas.

A man of many hats

Like de la Hoya, Pacquiao has walked through many of the doors that pugilism has opened for him. He is currently a congressman in Sarangani Province, following the lead of fellow Filipino sports icons Robert Jaworski and Freddie Webb who parlayed their athletic success into politics. There are even talks of him running for senator in 2016.

There have been movie roles that ranged from forgettable to unintentional self parody. There was his debut CD, which included a cover of “Sometimes When We Touch.” There have been variety shows (which reach the apex of influence among the impoverished in the Philippines).

All of this equates to increased popularity in his homeland, where he remains one of the most sought-after commercial pitchmen for any and all products. It also takes away from time he could be in the gym, resting and reflecting on his next in-ring encounter.

But that is the paradox that affects geniuses across many planes. Brilliant musicians and artists notoriously self-sabotage, and that’s part of what makes them so enthralling. Pacquiao, a genius of fisticuffs, has always been his greatest enemy.

Timothy Bradley Jr, by contrast, is a stranger outside of boxing. Bradley is a two-division champion from Palm Springs, California who, despite being unbeaten at 31-0 (12 KOs), has not yet achieved the popularity and acclaim that other less-accomplished fighters have. He was booed heartily by the crowd after being announced the victor against Pacquiao. And after Ruslan Provodnikov. And after Juan Manuel Marquez.

So far he has (officially at least) beaten every man put before him in the ring. What makes his accomplishments most remarkable is that he has done so while not being above average in any quantifiable attribute. His most serviceable asset has been his desire to win.

Bradley walks around with a chip on his shoulder, and when he was dropped and battered by Provodnikov, he traded back until he was able to assume control. Against Marquez, when his opportunity to win was fading, he walked around the ring with his hands down, stepped in and delivered a left hook that nearly dropped Marquez and earned him the decision.

There is never concern that Bradley may be overlooking an opponent or giving anything less than his all in training. Alongside long-time trainer Joel Diaz, Bradley has consistently worked himself into peak condition, overachieving through the sacrifices he makes in the gym.

Manny Pacquiao is still faster than Bradley, a heavier puncher than Bradley and more experienced than Bradley. You’d be lying to yourself if you said he was not hungrier than Pacquiao, and a fighter with greater desire and the proper game plan can sometimes overcome such disadvantages.

Whether Pacquiao wins or loses is immaterial. Though Pacquiao maintains that his “time is not yet finished,” that time is quickly approaching.

It may not come against Bradley. He may put together another great performance, like the one he turned in against Ricky Hatton when he knocked the Briton cold in two rounds and effectively ended his career. He may avenge a loss for the first time since the Erik Morales knockout of 2006, earning a 5th fight with Marquez on the next stop of his revenge tour. But the day will come.

Perhaps at this point retirement would be a welcome respite for Pacquiao, who has set a fine example of citizenship with his philanthropy and charity. Pacquiao is a national treasure in the realest sense, capable of making victims of the world’s strongest recorded typhoon in Leyte, Philippines forget about their horrors and frustrations with just his very presence.

His calling outside of the ring may be greater than his calling in the ring.

No opponent who manages a victory over him in his twilight; no tax man dragging his name through the mud to steal headlines; no loss of the fortunes he has amassed can rob Manny Pacquiao of the unprecedented accomplishments he has achieved in the ring.

But all good things come to an end. It’s just a matter of when. – Rappler.com

Ryan Songalia is the sports editor of Rappler, a member of the Boxing Writers Association of America (BWAA) and a contributor to The Ring magazine. He can be reached at ryan@ryansongalia.com. An archive of his work can be found at ryansongalia.com. Follow him on Twitter: @RyanSongalia.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.