SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

NAGOYA, Japan – “I am a champion, and you’re gonna hear me roar.”

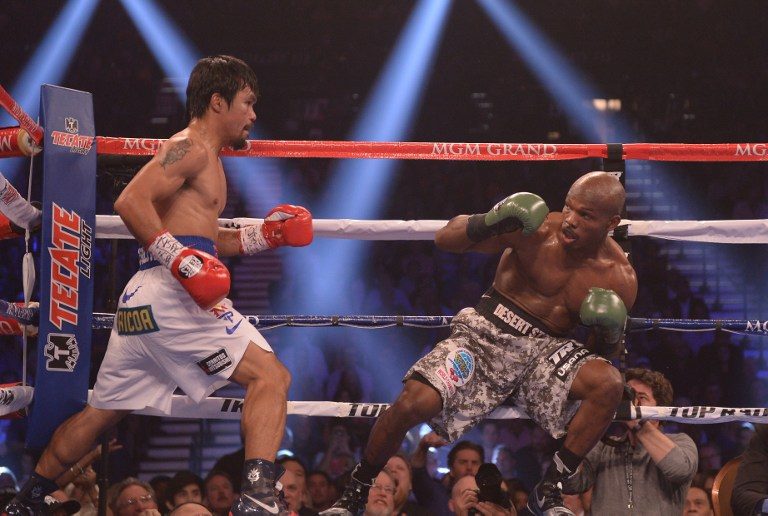

The crowd at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas turned rapturous as the chorus from Katy Perry’s “Roar” blared over the Arena’s sound system. With lights the color of the Philippine flag draped over the venue, Manny Pacquiao walked toward the ring for his rematch with Timothy Bradley to a crowd that favored him at a 99-1 ratio.

Undoubtedly Pacquiao has selected the poppy anthem with lyrics that reference boxing icons like Rocky Balboa (“Eye of the Tiger”) and Muhammad Ali (“floating like a butterfly, stinging like a bee”) as his rallying message to adorers that, though he’s not the fighter he once was, he is still a great champion. In 8 divisions, no less.

The first Bradley fight in June of 2012, called by many “the worst decision in boxing history,” was the sort of injustice all Filipinos could relate to. From the days of colonialism to today’s corrupt political environment, wrongs are openly acknowledged but rarely, if ever, rectified.

But last Saturday, Manny Pacquiao got the opportunity to do something that many Filipinos wish they could: he took the law into his own hands. Facing a younger, if similarly battle-worn foe, Pacquiao fought neck-and-neck with the American champion for 6 rounds before turning the fight in his favor in round 7.

Awakening his mean streak, Pacquiao (56-5-2, 38 KOs) rocked the resolute Bradley into the ropes before unleashing a volley of punches that sought to remove the 30-year-old from Palm Springs, California, from consciousness. Whereas in recent years Pacquiao would step back and ask the referee to spare his foe from lasting damage, Pacquiao unloaded mercilessly, forcing Bradley to employ a 4-corner defense to avoid being knocked out.

Pacquiao won a unanimous decision despite outlanding Bradley by a smaller margin than he had in the first fight (198 to 141 in second fight, compared to 253 to 159 in first fight).

Pacquiao beat his weary foe as if he was an amalgamation of the detractors who said he was a spent force after suffering the first loss to Bradley, followed by the sixth-round knockout loss to Juan Manuel Marquez.

“You held me down, but I got up, already brushing off the dust…”

The Pacquiao who avenged the loss to Bradley wasn’t the best version of himself that had graced the ring. Freddie Roach, Pacquiao’s long-time trainer, admitted that Pacquiao lacked the explosiveness he had in the first fight.

“He didn’t seem to have the power that he usually has,” Roach said. “He was a little bit slower than I’ve seen him in the past.”

Manny Pacquiao’s best days belong to another decade. It’s unrealistic to expect the sort of brilliant displays of violence that he had shown in ending the careers of noted Western boxing icons Oscar de la Hoya and Ricky Hatton, or making Erik Morales quit, on a consistent basis.

But what he may have lost in physical ability he makes up for in desire. Pacquiao, with his renewed dedication in the gym and performances in the ring, is showing that he still has the will to be a champion, to overcome the degeneration of age. By pushing himself in training, he’s able to make the most of his dulling physical prowess.

As Pacquiao’s career winds down, the question that begs to be answered is: what is his exit strategy?

Fight of all fights

At the post-fight press conference, Pacquiao’s promoter Bob Arum gave the assembled media the names most expected to hear associated with Pacquiao’s next fight date later this year. The winner of the Marquez-Mike Alvarado fight would be easy to make, as the Denver, Colorado, native Alvarado is signed with Top Rank and Marquez is co-promoted by the company. Arum also named Ruslan Provodnikov, a former Pacquiao sparring partner whom Top Rank co-promote with Banner Promotions, as a potential opponent.

Predictably, few media men were overawed by the prospects of those fights, and instead directed their line of questioning toward the subject of the elusive Floyd Mayweather Jr fight. It’s the biggest fight to never happen, and both are the only foes the other has left to prove anything against.

A win over Floyd Mayweather Jr would validate Pacquiao as a Filipino folk hero on a par with seditionist prosist Jose Rizal and Ninoy Aquino, a fellow politician whose 1983 assassination at the airport now named after him left him lying dead in the same face-down position that Pacquiao would find himself in after his knockout loss to Marquez.

The frustration with Filipino boxing fans stems from Mayweather’s reluctance to fight Pacquiao, which originates from a mixture of business differences between their camps and – possibly – the realization that Pacquiao represents the single greatest threat to Mayweather’s undefeated record.

Pacquiao would doubtlessly be an underdog to the 45-0 Mayweather, a perfectionist whose philosophy is to win inside and outside of the ring by any means necessary. Mayweather has said that the 3 remaining fights in his contract with the Showtime network after his May 3 bout with Marcos Maidana are the last 3 he has left.

This writer spoke with Mayweather’s advisor Leonard Ellerbe while in Las Vegas. Ellerbe refused to speculate on the chances that Pacquiao fills one of those 3 remaining engagements.

Arum’s position that Top Rank is prepared “to sit down at a table with his people to work out the conditions for the fight” is novel, but difficult to imagine. A Cold War has divided the sport between networks, promoters and – after MGM Grand covered their property with Mayweather-Maidana propaganda in time for Pacquiao-Bradley II – casinos, and the likelihood that these bitter rivals would set aside their conquest for control of boxing for the common good isn’t great.

Win or lose, Pacquiao could bring his career to a conclusion with no regrets off that fight. There’d be nowhere else to go afterwards.

None before him, none to come

The persistent question that every Filipino boxing pundit has been asked at least a dozen times – “Who is the next Manny Pacquiao?” – can only produce one accurate answer: no one. There will be another Manny Pacquiao when there is another Muhammad Ali, Joe Louis, or Mike Tyson.

Pacquiao is the perfect storm of socioeconomic familiarity and athletic greatness that appeals and relates to the common man. It’s highly unlikely that another fighter will come around in our lifetime that has the credibility among Filipinos and the greatness to appeal to Americans.

Pacquiao is a native born, locally-raised Pinoy with the same tastes for rice and karaoke as his constituents. He comes from humble beginnings, raised in abject poverty in General Santos City, where he wandered the streets in search of odd jobs to earn enough pesos to eat for the day. His rise to success is more unlikely than any melodramatic teleserye would ever feel comfortable pitching to a network head.

At his prime, he was a brazen warrior, a modern day Lapu-Lapu, who banged his gloves together defiantly when hurt, and raised his arms antagonistically as he assaulted foes. He was brash without being mayabang, making audacity acceptable in a culture that frowns on any exhibitions of boastfulness.

With how overexposed Pacquiao has become, it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that he’s a product of the people, not the marketing sector. Pacquiao remains one of the few faces on the billboards that line the highways of Manila that look like the products’ target demographic.

Foreign-based Filipinos, for all their recent accomplishments in boxing, have been dismissed as Filipino-Americans or, as some divisionists are fond of remarking, as “not one of us.”

Pacquiao has also fought at weights that few Filipino boxers have ever competed at, the heavier divisions that are bankable in America. Ceferino Garcia, the Biliran-born middleweight champion of the ’30s and ’40s who once held the great Henry Armstrong to a draw, is the only other Filipino to win a world title over the junior welterweight division.

The closest the Philippines had come to a native born dominant champion in recent years was Bacolod’s Gerry Peñalosa, a titleholder in two divisions who had few big fight opportunities come his way because he fought below featherweight. No less than Roach described Peñalosa as the greatest Filipino boxer ever from a skills standpoint, but boxing politics and hometown decisions ultimately cost him his title and drove him from the sport in his physical prime.

Any athletically-inclined Filipino above 5-foot-9 would settle for the less demanding, if more ceilinged, path as a domestic-level basketball player. Boxing is a sport that attracts the poorest of the poor who are willing to risk their life and health for a longshot chance at finding fortune and prosperity. Any quality athlete of above-average size is being scouted from middle school age toward the nation’s preferred sport.

The same is true for America, where the lack of credible American heavyweights is blamed on the explosion in popularity of the National Basketball Association and the National Football League.

After completing post-fight interviews, Pacquiao, with blood streaming down his face, stood on the ring apron and soaked in the fans’ adulation. He knew that these nights were in short supply now, and so did the fans.

There will come a day when Pacquiao isn’t able to awaken the doldrums of his fighting spirit. Boxing cannibalizes all of its greatest warriors, and the man who lifted Filipinos as a people will need his people to stand by him as he transitions into a post-boxing life.

Appreciate him while he’s here, because he won’t be around for much longer. There has never been another Filipino fighter like him, and there never will be again.

Louder, louder than a lion, ‘cause I am a champion, and you’re gonna hear me roar. – Rappler.com

Ryan Songalia is the sports editor of Rappler, a member of the Boxing Writers Association of America (BWAA) and a contributor to The Ring magazine. He can be reached at ryan@ryansongalia.com. An archive of his work can be found at ryansongalia.com. Follow him on Twitter: @RyanSongalia.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.