SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Daenerys Targaryen: Lannister, Targaryen, Baratheon, Stark, Tyrell they’re all just spokes on a wheel. This one’s on top, then that one’s on top and on and on it spins crushing those on the ground.

Tyrion Lannister: It’s a beautiful dream, stopping the wheel. You’re not the first person who’s ever dreamt it.

Daenerys Targaryen: I’m not going to stop the wheel, I’m going to break the wheel.

Followers of George R.R. Martin’s bestselling novels and hit HBO television series Game of Thrones would agree that Daenerys Stormborn Targaryen is one of its most compelling characters. Daughter of a fallen king, she faced all adversities to (literally) walk out of fire and become the mother of (literal) dragons. She then becomes the Khaleesi (chieftain) of the warrior Dothraki tribe and begins a quest to free all slaves from the various kingdoms of Westeros and rightfully claim the throne that was stolen from her father. (WATCH: Can Grace Poe sit on the Iron Throne?)

Grace Poe’s emergence as a potential “third force” in Philippine politics has led many commentators to ask if something fundamentally new may be emerging this presidential season: a major candidate who is neither backed by the administration nor is seen to lead the opposition to it.

But a look back at previous post-Marcos elections suggests a very different interpretation is more plausible.

Poe, like all major presidential contenders, has aligned herself with one of the two major “narratives” of Philippine politics, that of “reformism” or “good governance” carried out by “moral leaders.”

She is seemingly aligned against a “populist” narrative of helping the poor against an uncaring elite that Vice President Jejomar “Jojo” Binay has made his own following in the footsteps of former president Joseph Estrada. (READ: Battle of Aquino, Binay narratives)

Thus it is not surprising that Poe has won strong support from the middle and upper classes while basking in the favorable publicity provided by the press. In the same manner, Binay enjoys a core support of the poor while being denounced as corrupt by many key elites.

Bridging narratives

Despite failing to get the anointment of President Benigno Aquino III, she remains a viable candidate because of the way she is “selling herself” to the public.

Although the daughter of the late Fernando Poe Jr, Estrada’s close friend and even more popular movie-star politician, she has not yet taken on her father’s populist mantle. FPJ, it should be recalled, was much feared by most key elites and attacked by much of the press.

Grace Poe, by contrast, is a darling of the well-to-do with her image as an honest reformer, cultivated during her earlier minor government position and her leadership of key Senate investigations (particularly the probe into the Mamasapano massacre). Crucially, she endorsed a Senate report recommending corruption raps be filed against Binay, ignoring his claims of selective persecution.

These have won Grace Poe support not just from elites but also from the “masa” – but of a different kind her father enjoyed. She is not posing as the friend of the friendless poor as Estrada (“Erap para sa mahirap”) or as her father did against an uncaring elite. Rather she is following the familiar reformist script of asking voters’ support because that they can trust her as an honest, “good” person whose integrity is not in doubt.

This is the same strategy that Aquino used in 2010, drawing on his bloodline to his illustrious parents Cory and Ninoy whose morality seemed beyond repute (the former as a modern day saint and the latter as the country’s greatest martyr since Jose Rizal). Noynoy Aquino was thus a “good dynast” who could be trusted to carry out the reforms the country so badly needed which the devious “bad dynast” Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo had so failed to do as president. (This negative narrative, of course, overlooked the fact that Arroyo was fighting for her political survival after only narrowly “defeating” the populist Poe, a crooked victory her elite supporters were happy to overlook until the “Hello, Garci” scandal made it impossible to do so).

Thus, although seemingly predestined to make populist appeals, through the current political situation and her own background, Grace Poe has become a darling of the elites. She is wooing the Filipino masa based on cross-class appeals and not the divisive calls to “class war” that Estrada made when the Makati Business community, the Catholic Church hierarchy, and civil society turned against him, leading to his ouster in 2001.

Yet, she is unique in the sense that she can actually bridge the two narratives.

Against the Yellow and Black Knights

Ultimately, Aquino endorsed the presidential candidacy of Mar Roxas due to his utang na loob (debt of gratitude) to Mar for stepping aside in 2010 (and perhaps even more so to Mar’s mother Judy Araneta Roxas, a Liberal Party stalwart also close to Ninoy and Cory).

Mar will try to compete with Grace (probably not very effectively) for the mantle of the best reformist candidate in the campaign. These reformist candidates would then be pitted against Binay’s increasingly militant populism. With so little support among the elite, Binay has little to lose by appealing directly to the poor by denouncing the country’s oligarchy.

Binay will counter charges of corruption with claims of selective persecution, fueled by his willingness to do something for the poor, as demonstrated by his impressive record of providing social welfare as Makati mayor and his efforts to help overseas workers as vice president.

Poe has so far aligned herself with the same “reformist,” good governance narrative that Aquino so effectively employed in winning the 2010 presidential election and has, with a surprising degree of success despite major setbacks, continued to hold.

Although for the middle and upper classes Binay’s presidential bid has been hopelessly tarnished by the ongoing plunder case for a supposedly overpriced parking garage said to involve payoffs, his supporters claim this was instigated by Aquino allies, particularly Mar Roxas, to undermine his candidacy and to distract from the fact that he offers a real alternative to the poor of the Aquino “boom years,” which however did little to reduce poverty.

Binay became a national political figure through his promotion of social welfare when he was mayor of Makati, Metro Manila’s business district. Aquino’s supposed “straight path” did little to ease the plight of the country’s poor who lack access to decent jobs, adequate education, health care and other social services.

Poe’s non-anointment actually gives her the space to address the unfinished business of Aquino’s “Matuwid na Daan” and cut into Binay’s populism. She can cloak herself with the mantle of her father FPJ and continue his vision of “Bayan ang Bida” (the people are the hero). She can articulate a comprehensive social reform agenda that will emancipate the poor from the shackles of poverty. (READ: Mapagpalayang daan: The third way)

Interestingly, unlike Estrada, a populist hated by elites, or Arroyo, who was seen to have betrayed the reformist cause, Aquino has been able to “bounce back” from the pork barrel scandals and the Mamasapano tragedy that threatened his reformist narrative.

Like Fidel Ramos, who also shook off accusations of scandal thanks to strong elite support and favorable press coverage, Aquino also had the full support of the major elite “strategic groups,” particularly big business, most civil society activists, and the media. The Catholic Church hierarchy is an exception due to the brouhaha over Aquino’s reproductive health law, which the Supreme Court has now toned down and partially depoliticized. Arroyo could not bounce back after “Hello, Garci” and subsequent scandals because major civil society groups and parts of the military remained vehemently opposed to her administration.

In other words, without elite support scandals do not necessarily hurt a president that much or at least for that long.

Heroic quest

There are many unknowns between now and next year’s presidential election including whether Grace Poe will actually be a candidate, and if she is, whether questions regarding her citizenship will flourish to disqualify her from seeking the presidency.

But in assessing the potential significance of her candidacy, the view should not be too narrowly focused on her relationship to the Aquino administration. Rather it is her credentials as a “reformist” that are of crucial importance.

Enjoying strong middle and upper class support, she is well positioned to mobilize a similar part of the electorate as Aquino did in his “straight path” campaign of 2010. While Mar Roxas might cut into her “reformist” support some, the real issue is the fact that five years of “exclusive” economic growth have left many of the country’s poor no better off than before Aquino’s presidency, and whether a strong “populist” challenge (by Binay or even another Estrada candidacy) might be the stronger campaign narrative in 2016.

The challenge for Poe is to articulate a clear vision and comprehensive program of government that will address the reformist concern for good governance and the populist cry for social justice. She needs to channel her popularity into a movement that will finally unify this fractured country and actually break the unjust wheel of patronage and poverty in the Philippines.

Joseph Campbell, in his classic work “The Hero with a Thousand Faces,” speaks of a “monomyth” that underscores all mythologies and legends around the world.

According to Campbell, “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

Similarly, Grace Poe is about to begin her own political quest, with a myriad of nefarious challenges strewn along her way. Her father, Fernando Poe Jr, or FPJ, was Panday (the Blacksmith), the legendary King of Filipino movies. FPJ was triumphant in all of his movies, but failed and eventually perished in the darker realm of realpolitik.

Only time can tell whether Grace Poe will succeed in her own “heroic quest.” She can draw strength from the fact that she is the Anak ng Panday (Child of the Blacksmith). – Rappler.com

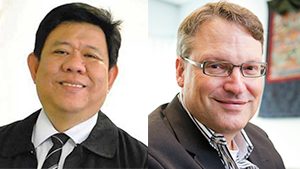

Julio C. Teehankee is Full Professor of Comparative Politics and Dean of the College of Liberal Arts at De La Salle University. He is also the Executive Secretary of the Asian Political and International Studies Association (APISA).

Mark R Thompson is acting head of the Department of Asian and International Studies and director of the Southeast Asia Research Centre, both of the City University of Hong Kong.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.