SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

A version of this article was originally published by The National Interest in Washington, D.C.

In recent days, anti-China hysteria has reached a new level, with some media outlets alleging that China may have had issued a hidden threat to the Philippines in a recent newspaper publication. A more careful understanding of China’s statements in recent years may actually point at a very different interpretation: China could be actually warning about the supposed possibility of the United States or Japan – as the oriole/sparrow – taking advantage of disputes between the Philippines and China (the mantis and the cicada) to push for their own interests, or that the two neighbors are forgetting the bigger context of their bilateral relations by focusing too much on the maritime disputes.

In fact, for those who study China’s domestic media, it is clear that there is no single voice expressing the authentic/final position of the top leadership (See Evan Osnos’ excellent new book, Age of Ambition). In fact, recent years have also seen the growing irrelevance of the Chinese Foreign Ministry in shaping the country’s foreign policy, as other powerful interest groups pitched in. So even the foreign policy of China is a negotiated outcome of inter-agency jostling. In short, you can’t decipher China’s foreign policy by looking at newspaper clippings or simply the statements of a single agency. Yet, one can’t deny the dangerous uptick in China’s territorial assertiveness at the expense of its neighbors, especially the Philippines.

For years, the Philippines has been hailed as the courageous David that took the Chinese Goliath to the court. As the weaker country, the Philippines has sought to leverage prevailing international law, specifically the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to challenge China’s dubitable doctrine of “historical rights” and notorious Nine-Dashed-Line claims in adjacent waters. As far as the West Philippine Sea is concerned, the Philippines’ trademark approach is “lawfare” (legal warfare).

None of the other claimant states, from Vietnam to Malaysia and Brunei, have dared to adopt a similar measure against mighty China, though Vietnam has been quietly making some preparations, currently assessing whether the Philippines can overcome the jurisdictional and admissibility hurdle at The Hague.

Lacking full-fledged sovereignty, Taiwan – considered as a renegade province by Beijing – is no position to launch a credible lawfare, even though it occupies the most coveted naturally-formed feature in the area, the Itu Aba (Taiping to locals), and controls the Pratas chain of islets close to the Northeast Asian theatre. No wonder then, Taipei is more interested, and feverishly advocating for, joint-development and exploitation of resources in the contested areas. (But things could change if the pro-independence opposition Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) wins in the upcoming elections, especially in an era of growing anti-Mainland sentiment in the country.)

The Philippines’ lawfare strategy falls under the rubric of what I call the “Moralpolitik” of the Aquino administration, which came into power in 2010 on the heels of a moral crusade against a rotten state apparatus. Over the years, not only did President Benigno Aquino III seek to hold his predecessor (Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo) to account, but he gradually also recalibrated years of increasingly cordial and quasi-subservient relations with Beijing that reached its zenith in mid-2000s.

For much of the world, it is clear that China, as the bigger power, is flexing its muscle in contravention of international law, regional norms such as the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DoC), and the welfare of weaker neighbors like the Philippines. Seen against this backdrop, without a question, the Philippines’ legal-moralistic approach deserves global applause.

Intent on preserving “moral high ground” amid a protracted legal dispute with China, the Philippines, however, has shunned any significant refurbishment of its dilapidated facilities in the Spratly chain of islands, just when all other claimant countries have been fortifying their position amid China’s massive reclamation activities, which are giving birth to the skeleton of an Air Defense Identification Zone in the South China Sea.

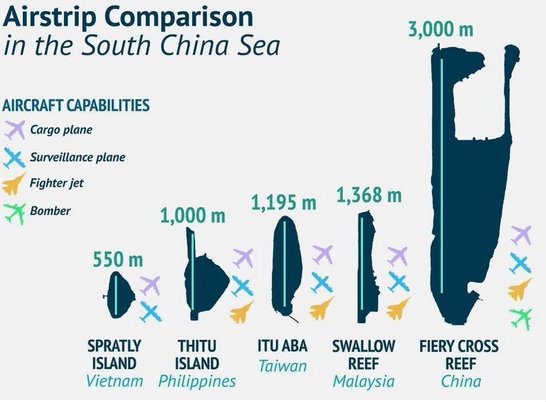

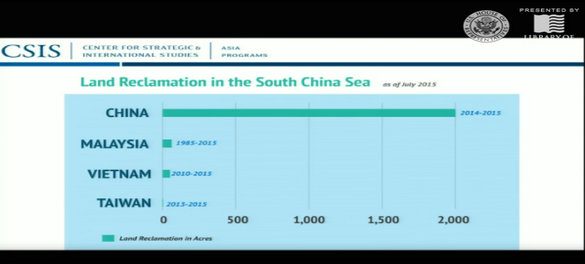

There is even growing worry that China maybe intent on building facilities on the Scarborough Shoal, which falls well within the Philippines’ 200-nautical-miles Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). And unlike other claimant states, China, which has built a 3 kilometers-long airstrip on Fiery Cross – a contested reef that was expanded by 11 times its original size – can now project power from its artificially-created islands in the area (See figure 1). Thus, my worry is that our commitment to moralpolitik – constantly talking about moral high ground, but not preserving strategic high ground – may come at the expense of the urgent necessity to make necessary countermeasures.

A principled foreign policy

In The Rise of China vs. the Logic of Strategy, leading strategist Edward Luttwak correctly points out that much of China’s recent maritime assertiveness has to do with Beijing’s pre-mature sense of triumphalism in the aftermath of the 2008 Great Recession, which severely undermined the industrial-financial underpinnings of American power.

Just like many other smaller states, the Philippines, which was at the receiving end of China’s maritime aggression over the Scarborough Shoal in mid-2012, has been only responding to the belligerence of a more powerful and ambitious neighbor. In short, the Aquino administration has been simply reacting to China’s actions, rather than actively shaping the texture of bilateral relations with Beijing.

It is unfair and groundless to blame the Aquino administration as the primary reason for the toxic nature of bilateral relations with China. A basic fact in world politics is that it is the great powers that have the agency to shape the dynamics of international system — rarely the case with weaker nations like the Philippines. Yet, there is something unique with Aquino’s approach.

With respect to China, there is tremendous reluctance vis-à-vis high-level bilateral dialogue and robust trade and investment relations. The Aquino administration is adamant that bilateral dialogue with China is practically worthless, since Beijing is yet to show good will, while openly expressing doubts vis-à-vis the independence of and motivations behind the establishment of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). No wonder then, the Aquino administration has repeatedly turned down offers of negotiations and bilateral dialogue with China, while postponing formal membership in the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

There is also a tremendous (over)emphasis on an inherently risky legal approach and maintaining “moral high ground”. More than two years into our legal complaint against China, we are still waiting for whether the Arbitral Tribunal will exercise jurisdiction on the issue to begin with (see my comprehensive analysis of the Philippines’ arbitration procedures for The National Interest, entitled “The South China Sea Showdown Heads to Court”). From the point of view of the Aquino administration, it is waging a brave, moral crusade against a mighty hegemonic power.

In a recent exchange with Philippine Foreign Secretary Albert Del Rosario, he emphasized the nature of the country’s principled, independent foreign policy. When I asked him about reclamation activities of other claimant countries, particularly China and in recent months, he told me that it’s very important for the Philippines “to go to the court with clean hands.”

I raised the point on reclamation activities in light of the Aquino administration’s decision to once-again postpone the refurbishment of its creaking facilities and airstrip on Thitu Island (Pag-Asa), just when other claimant states, including Taiwan, have been upgrading their facilities in the Spratly chain of islands (See figure 2). Vietnam is being accused of undertaking mini-reclamation activities on some of the features it controls in the area.

The other fight

In the meantime, China has reclaimed 810 hectares across disputed waters in less than two years, while Taiwan has allocated at least $100 million to upgrading its facilities on Itu Aba, Vietnam has allegedly made reclamations on some of the features under its control, while Malaysia is still relishing its sophisticated facilities and airstrip on Swallow Reef, which it upgraded back in 2003. With the exception of the Philippines, other active ASEAN claimant countries have been engaged in upgrading their facilities even after signing the 2002 DoC

Ironically, Manila, during the Cold War, was actually among the first countries that built a modern airstrip in the area, acknowledging the necessity of maintaining strong presence on the ground. But now the Philippines has among the least-developed and most under-maintained facilities in the area. Just look at our ragtag outpost (Sierra Madre vessel) on the Second Thomas Shoal, which has been at the receiving end of Chinese Coast Guard forces’ intimidation and siege tactics since 2013; it is a poignant reminder of the Philippines’ decades-long strategic complacency, which is costing it dearly. For the past 16 years, the country has precariously hosted – on a rotational basis – few, marooned Filipino troops on a rusty, grounded vessel in order to guard its claim over the contested shoal.

The Philippines had no outposts close to the Scarborough Shoal, which it lost to China in 2012. Same can be said about the Mischief Reef, which it lost in 1994. If there were Filipino outposts and troops stationed in Scarborough Shoal and Mischief Reef, they would have been, at least theoretically, covered by the Philippine-US Mutual Defense Treaty, especially if they came under direct assault by other claimant states. So outposts have a deterrence value, no matter how tenuous. Only recently did the Philippines decide to undertake desperately-needed maintenance operations to reinforce the hull and deck of the dilapidated World War II relic in Second Thomas Shoal.

Overall, the Aquino administration’s “Moralpolitk” – injection of morality into foreign-policy discourse -–has managed to mobilize the Southeast Asian country against a tough neighbor. I have my utmost respect for the Aquino administration and the Department of Foreign Affairs, who have shown their sincere commitment to protecting our national interest, abiding by international law, and not succumbing to carrots and pressure. But we have to also make sure that the moralistic approach will not come at expense of more tangible means of defending the Philippines’ claims and national interest. – Rappler.com

Richard Javad Heydarian teaches political science at De La Salle University, and is the author of “Asia’s New Battlefield: US, China, and the Struggle for Western Pacific” (Zed, London). He is a regular contributor to Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative of Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington D.C.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.