SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Death has always played a central role in Philippine life. The practice of mourning, or lamay in Tagalog, has long energized the families and communities of the dead, drawing them together around the corpse to send it on its way.

The dead is an absent presence – an ineluctably paradoxical and powerful figure – the control of which is believed to lie at the basis of social life. In this sense, the loss of a loved one is both promise and threat. In the pre-colonial period, realizing the former while preventing the latter required rituals of mourning. The dead were transformed into figures of respect and deference – that is, into ancestors to whom the living address petitions for blessings and protection. At the same time, the living render offerings with which to ward off any malevolent ghostly returns.

Spanish Christianity capitalized and altered this ancient practice of mourning the dead. Colonized lowlanders were compelled to celebrate less the resurrection as the passion: the humiliation and the bloodied murder of Christ as seen in the Pasyon, the Cenaculo, and the omnipresent depictions of his mangled, wounded body on the cross.

With the rise of nationalism, death became a potent political issue. As several scholars have pointed out, Jose Rizal’s manner of dying proved to be far more significant than his way of living, spurring people to join the Revolution against Spain. Often referred to as the “Filipino Christ,” his corpse was so powerful that his family sought to protect it, by burying it in a secret grave in Paco to prevent others, including the Spaniards, from digging it up and dumping it in some unknown spot. The singular importance of Rizal’s death is such that his remains were eventually transferred close to the place of his execution where his monument is a kind of cemetery built for him and him alone. While details of his life are complex, the fact of his death is simple enough so that he could serve as the chief icon, some would say fetish, of the nation.

Compare the death of Rizal with that of other heroes. Bonifacio’s judicial execution and Luna’s extrajudicial killing were carried out not by the enemies of the revolution but on the orders of the first Filipino dictator, Aguinaldo. Their death, unmourned by the nascent nation, split the revolutionary forces apart and set the stage for collaboration with the American forces.

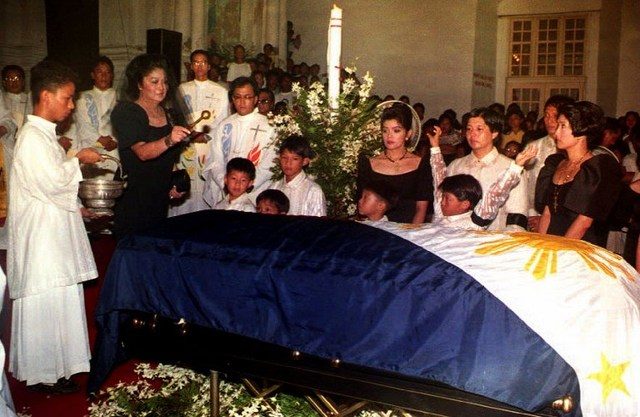

Ramon Magsaysay’s death, because it was accidental, was widely mourned but was never politicized. By contrast, Ninoy’s assassination by figures whose identities remain shadowy had tremendous historical consequences. His death echoed in the minds of many the execution of Rizal and the Pasyon of Christ. He was mourned for over three years, and at the end of it, people came together at EDSA (and other places around the archipelago) for a massive show of damay. Collective mourning as political expression spilled into the streets and evolved into practices of resistance that halted the military, impressed the world, and forced the Marcoses to flee in the dark, much like the hasty burial of Ferdinand a few days ago. Cory, his widow, infused by Ninoy’s martyred legacy, went on to govern in his name.

Death of OFWs

In the post-EDSA period, we witnessed the massive outpouring of mourning for Flor Contemplacion, the OFW accused of killing her Singaporean ward. Most Filipinos thought she was wrongly accused, and pleaded for mercy from what seemed like a callous Singaporean state. She epitomized for many the “heroism” of so many OFWs, especially women, forced to leave their own family (another theme in the narrative of heroism: departure, exile, persecution, and death so that others may live). Copious tears shed by Nora Aunor in the film version of her life and death tied together the country and translated into a collective feeling of being persecuted by the governments of both Singapore and the Philippines. Underlying this sense of persecution was also gendered feelings of guilt and shame for having allowed “our women” to be exploited by foreigners.

Yet, the death of Flor and other OFWs then as now never did escalate to calls for regime change. Why? Perhaps because OFWs, like many of the poor people daily gunned down, are seen as contractual workers with little or no rights, and so disposable in both material and symbolic senses. For that reason, compassion for them seems transient and episodic at best. As in life so in death: those on the margins are less likely to stir national compassion as those from the elite sectors of society.

And so it was with Cory Aquino’s own death exquisitely timed to coincide with the corruption scandals that beset the regime of Gloria Macapagal Arroyo. In contrast to Gloria, Cory’s life was mythologized, her “sins” wiped away. Her saintliness was fully restored, thanks to the necrological aura that was deeded to her by Ninoy, whose own messy political past was sanctified by virtue of his assassination. As with all martyrs, death became the standpoint from which to regard their lives. Cory’s necrological aura was then passed on to her son, Benigno III. He combined the hallowed name of the father with the “innocence” of the mother. In a great show of damay, the people propelled him to the presidency over his more technocratic, corrupt and charisma-challenged opponents.

Rodrigo Duterte’s ascendancy represents an inversion, but not an overthrow, of the political logic of mourning.

Among other things, he emerged from the growing disaffection over PNoy’s inability to show affection, especially for the dead and their survivors: the victims of Yolanda, Zamboanga, the Mamasapano policemen, all the way back to the hostage crisis that marked his first year. Perceived to be emotionally inept, he seemed incapable of awa and unable to exercise the most elementary forms of consolation.

By contrast, Duterte not only showed he cared, but that he was willing to kill others to show it. Like the action star Fernando Poe Jr, his apocalyptic posturing was backed up by his murderous record. Speaking in the vernacular, his dark threats were inflected by the idiom of Old Testament revenge. Duterte came across as the prophet ready to reckon with evil-doers, or at least those he designated as such: drug lords and drug users. In the pursuit of his mission, he respected only one law – his own.

Swept up by a near messianic frenzy, he was elected by a plurality of Filipinos drawn to his tall tales and hyperbolic promises to kill, and kill pa more. In doing so, he also seemed to expose himself to death, frequently announcing his willingness to die for the country: a hero before his time. That he could joke and cuss his way to this kind of pre-emptive martyrdom was seen by his supporters as an added bonus, proof of his earthy passion for the common man.

Politicizing the dead

In the wake of his election and in the midst of his obsessive war on drugs, we have all become familiar with the collection of bodies executed nightly, the signs of what Duterte and his chief of police consider to be progress.

Duterte uses these corpses to his political advantage. However, he has politicized the dead differently. He sees in the abjected, marked figures not occasions for mournful reflections but clear evidence of his sovereignty in the face of international and local criticisms against possible human rights violations. Reveling in the remains of the dead, he stands up to foreign norms as a way of safeguarding the putatively imperiled lives of his people. He is the punisher and the protector whose campaign slogan, after all, was “courage and compassion.”

Against the mounting numbers of the dead, mostly poor, mostly marginalized and forgotten, and thus unmourned except by those close to them, there now re-emerges another corpse: that of Ferdinand Marcos. While he has paid no heed to the sufferings of the families of those executed in his bloody drug wars, Duterte has been solicitous to a fault where the Marcos family is concerned. He had even made it a campaign promise to have the body of the father buried as a soldier and hero (in exchange, of course, for a yet to be disclosed campaign contribution from the eldest daughter).

Thanks to President Duterte, Marcos receives official awa and state-sanctioned damay. But this is not the case for others: those killed and left to bleed on the streets, and those who had been victimized by Marcos’s forces – tortured, raped, and salvaged. There is nothing for them: no recognition, only condescension and enforced oblivion.

Thus the politics of death whereby corpses speak and stand for contending claims about power, rights, justice, and vindication. Breaking out of their neo-liberal graves, the dead have returned to haunt the living, bringing them towards the edge of something, perhaps towards some sort of reckoning.

In sanctioning the dictator’s burial, the President has left other victims unmourned, re-politicizing the question of death that has long animated Filipino life. Unleashing the affective demands for pity and compassion, mourning has fueled yet again the calls for justice and accountability. – Rappler.com

Vicente L. Rafael teaches history at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.