SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The controversial burial of Ferdinand E. Marcos at the Libingan ng mga Bayani last week sparked a raging debate online about how the late dictator continues to affect Filipinos today.

On the one hand, the pro-Marcos camp has pointed out that Filipinos today benefit from a number of good things that Marcos championed, including the presidential decree on 13th month pay and several big infrastructure projects.

On the other hand, the anti-Marcos camp has rebutted that Filipinos today continue to suffer from the billions worth of debt that Marcos accumulated and plundered, the egregious human rights violations he sanctioned during Martial Law, and his bastardization of our democratic institutions.

We argue in this article that, 3 decades after he was ousted, Marcos continues to have a substantial yet invisible impact on Filipinos today: Were it not for his bad economic policies and mismanagement, the average Filipino today would now be enjoying an annual income 3 to 4 times larger than what he or she currently earns.

We lost two decades of development

In a previous Rappler article, JC Punongbayan and Kevin Mandrilla showed that one way to measure a country’s path to development is by looking at income per person (GDP per capita).

Although imperfect, GDP per capita is widely recognized as a useful proxy for measuring people’s welfare: The larger people’s incomes are, the more goods and services they can purchase and the freer they are in making choices for their own lives.

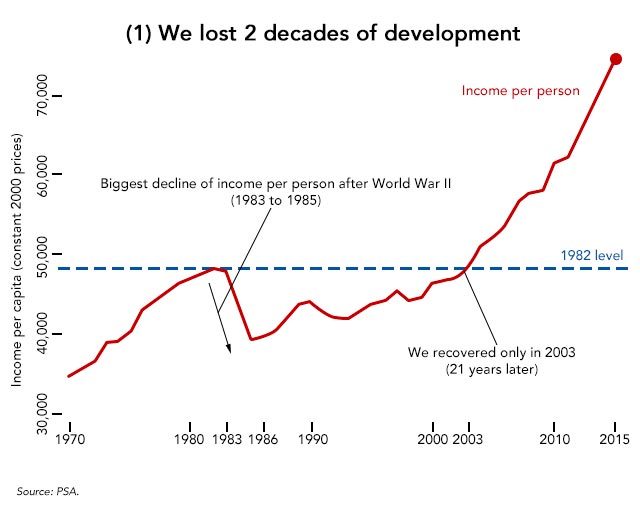

It bears repeating that, based on this metric, the Philippines lost two decades of development after the debt crisis in the early 1980s. Figure 1 shows that the Marcosian debt crisis put the country on a lower income trajectory. As a result, it took more than two decades for the average Filipino’s income to recover its 1982 level.

Importantly, no such downturn was observed in our ASEAN neighbors. In fact, their incomes grew by 2 to 4 times during the time it took us to just recover. This suggests that the Philippines’ “lost decades of development” were not unavoidable and were borne directly by Marcos’ policies.

What if we did things differently?

Looking back, one might ask: What if we had done things differently? What if the country had stayed on its original income trajectory?

Such “counterfactual” thinking is common in everyday life. By using the right kind of data and statistical models, we can similarly imagine hypothetical scenarios of what the average Filipino’s income would have looked like.

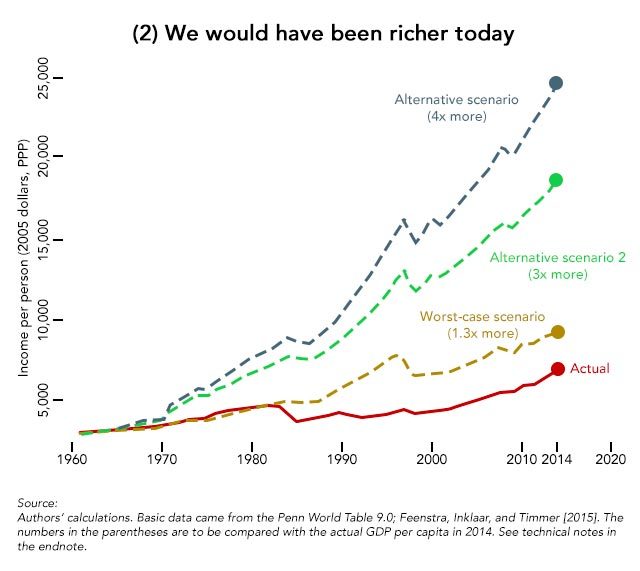

Figure 2 compares the Philippines’ actual income trajectory (orange trend) and certain hypothetical scenarios from 1965 to 2014 (blue, green, and brown trends).

The blue trend answers the following question: If we had replicated or mimicked the growth of our large neighbors – Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand – from 1965 onwards, how much more income would the ordinary Filipino have enjoyed today?

The green trend is just a more conservative version of the blue trend. The brown trend is based on our neighbors’ worst-case scenario: What if the average Filipino’s income grew at the same pace as our worst-performing neighbor in each year?

We would have enjoyed higher incomes today

As you can see, the actual income trend we experienced as a nation fared worse than all hypothetical incomes.

The blue and green trends deviated from the orange trend (actual income) as early as the late 1960s. This suggests that even during the early years of Marcos’ first term as president, the Philippines had started to stagnate vis-à-vis its regional neighbors.

Meanwhile, the brown trend deviated around the time of the debt crisis, and since then it even fared better than our actual income trend. In other words, Filipinos’ incomes grew even slower than our neighbors’ worst performers.

Most importantly, Figure 2 shows that we would have enjoyed much higher incomes today had we done things differently since 1965. The blue and green trends show that in 2014 the average Filipino would have enjoyed an income 3 to 4 times larger than what she or he was actually earning.

Think of how different your life would be if you earned 3 to 4 times more than your current income. Millennials earning a monthly income of, say, P30,000 could instead be earning somewhere between P90,000 to P120,000. Generally higher incomes would have improved the living standards of a vast majority of Filipinos and lifted so many families out of poverty.

Put another way, our results show that the average Filipino’s income today is just a fraction of what it would have been. Around the time of the debt crisis, we already lost as much as 50% of our potential income. As a result, the average Filipino’s income in 2014 was just 27% to 36% of its potential.

We would have been one of ASEAN’s richest countries today

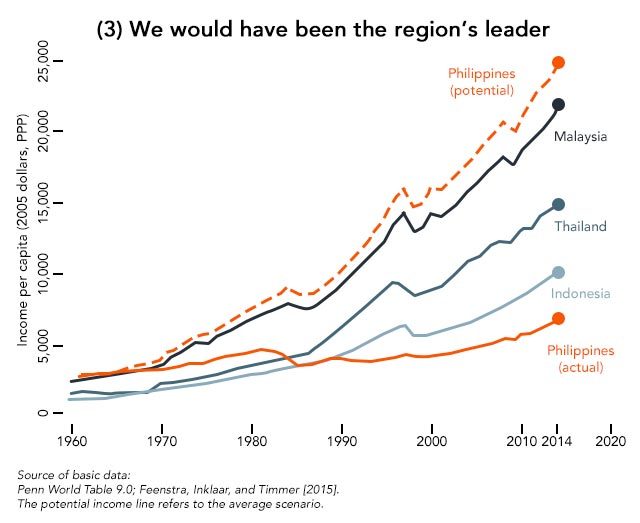

Furthermore, because of our deviant economic path during the Marcos era, we lost the opportunity to become one of the most prosperous countries in ASEAN. Figure 3 shows that by 2014 the Philippines would have been more prosperous than Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand.

Instead, we found ourselves becoming the region’s laggard, the “sick man of Asia”. One by one our neighbors overtook us, and soon, even Vietnam is poised to overtake us. Today we find ourselves needing to catch up with our neighbors rather than leading them.

Conclusion: Marcos stole our future as well

It’s bad enough that the Marcoses stole so much from the Filipino people already, from billions worth of ill-gotten wealth to last week’s swift and clandestine burial at the Libingan ng mga Bayani.

But the data suggest one more important fact: Ferdinand E. Marcos effectively “stole” the Filipino people’s futures as well by ushering in a full-blown debt crisis and dragging the country to a much lower income trajectory.

Were it not for Marcos’ bad governance, the Philippines would’ve been more prosperous today. Put another way, Filipinos today continue to reel from the impact of Marcos’ regime in terms of the potential incomes we have lost.

How do we move on from this intergenerational treachery? While we can’t turn back time to rectify our mistakes in the distant past, we can still avoid repeating the same mistakes in the future.

To ensure that our futures will not be “stolen” again, we should never again surrender our economic and political freedoms to charismatic strongmen with authoritarian tendencies. We should also make sure that our leaders do not implement short-sighted policies with little regard for the future well-being of Filipinos.

Maintaining a democracy is hard work, and our liberties are more fragile than most people think. That is why we should continue to engage ourselves in the running of our country by remaining vigilant and keeping a critical mind. No less than the future of our country is at stake. – Rappler.com

Technical notes for Figure 2: The data refer to GDP per capita in 2005 international dollars PPP (RGDPNA variable). Counterfactual trends for Philippine GDP per capita were generated using a Kalman-filtered state-space representation of the dynamic factor model (DFM) which extracts the shared co-movement of GDP per capita growth in Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia. Alternative scenario 1 shows the baseline DFM estimates. Similar results were obtained when the counterfactuals were computed using the simple average and median growth rates in our neighbors. Alternative scenario 2 assumes that the Philippines is, on average, less sensitive to the expansion of our neighbors’ GDP per capita.

JC Punongbayan is a PhD student and Teaching Fellow at the UP School of Economics (UPSE). Manuel Leonard Albis is an Assistant Professor at the UP School of Statistics (UPSS) specializing in time series analysis, and also a PhD student at UPSE. Their views do not necessarily reflect the views of their affiliations. Thanks to Kevin Mandrilla for valuable comments and suggestions.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.