SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

More than 3 decades have passed since EDSA 1. But have we Filipinos truly imbibed the democratic ideals and norms that EDSA 1 restored?

If you ask the current government, we’ve learned our lessons so well that it’s now “time to move on.” For this year’s EDSA anniversary, Presidential Spokesman Ernesto Abella said that, “The emphasis has shifted. It is no longer a celebration of the past… We can’t get stuck to the past.”

But advocates of civil liberties and human rights will tell you otherwise. Last November Chair Chito Gascon of the Commission on Human Rights said that President Rodrigo Duterte’s drug war is the “biggest challenge to democracy” since the Marcos regime. “Not since the Martial Law period are we observing real threats to the established rules of our democratic system.”

This year’s EDSA 1 anniversary is as good a time as any to revisit the state of Philippine democracy. We use data to show that despite Filipinos’ satisfaction with democracy, it is now under threat from the increasing disregard of civil liberties and human rights.

Filipinos still like democracy

Over the years, Filipinos have shown a strong and consistent preference for more rather than less democracy.

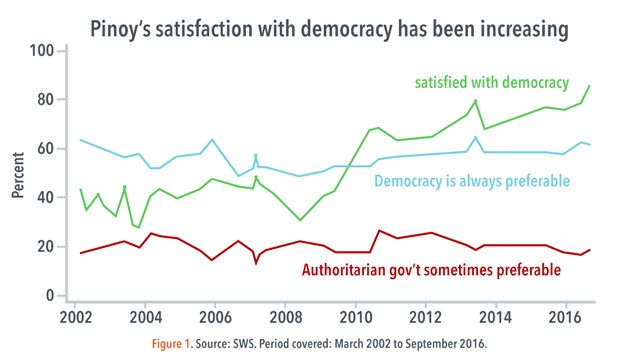

Data from the Social Weather Stations show that, as of September 2016, 86% of Filipino adults were satisfied with the way democracy works in our country. This is an all-time high as far as the data is concerned (see Figure 1).

At the same time, 62% of adults said that “democracy is always preferable” to authoritarianism, while 19% said that “under some circumstances, an authoritarian government can be preferable to a democratic one”. As seen in the graph, the former’s lead over the latter has been consistently large (blue vs. red trends).

But what exactly is ‘democracy’?

However, the very notion of “democracy” is quite difficult to define. So it’s hard to say what exactly Filipinos are “satisfied” with based on the surveys.

At present there are numerous attempts to pin down the concept of democracy using numbers. The idea is that, by doing so, we can objectively compare – however imperfectly – the level of democracy across different places and also trace how it changes over time.

Today some scholars use “thin” and “thick” measures of democracy. “Thin” measures equate democracy with basic criteria, such as the conduct of free and fair elections.

“Thick” measures, on the other hand, encompass other important pillars of democracy. These include a well-functioning government, a “culture of democracy” that shuns passivity and apathy, and – most importantly – the protection of civil liberties and human rights.

The last item is particularly important. Majority rule alone does not make for a democracy. Instead, democracy requires basic guarantees on civil liberties and human rights, including the protection of minorities. Without these prerequisites, a democracy is no democracy at all.

One of the more prominent thick measures of democracy out there is the Democracy Index produced annually by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). Started in 2006, the Democracy Index looks at the state of democracy in 165 states and territories using 60 indicators that fall under 5 main categories. Each country’s “democracy score” is then used to classify it into 4 types of regimes: “full democracy”, “flawed democracy”, “hybrid democracy”, and “authoritarian regime”.

The Democracy Index 2016 shows that only 5% of the world’s population live in “full democracies”, while 49% live in “flawed democracies”. Around 33% of people live in “authoritarian regimes”, while the rest live in “hybrid regimes”.

Most strikingly, on a scale of 0 to 10, the global democracy score fell from 5.55 in 2015 to 5.52 in 2016. This is because 72 countries saw a decline in their democracy scores over that period.

Also, for the first time, the United States was demoted from being a “full democracy” to a “flawed democracy”. This result made headlines worldwide, but the EIU was careful to note that this was not due to the election of President Donald Trump. Instead, it was due to Americans’ increasing distrust in their government.

PH democracy is increasing, but civil liberties are down

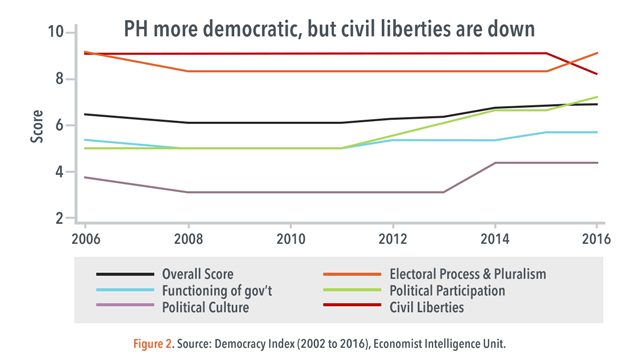

Based on latest Democracy Index, the Philippines’ ranking improved by 4 notches from 2015 to 2016. Indeed, our democracy score has been continuously increasing since 2011 (Figure 2).

But remember that this democracy score is the aggregation of our scores on all other dimensions of democracy. While our scores on the electoral process and political participation increased from 2015, for the first time our score on civil liberties dropped in 2016. From a constant level of 9.12 since 2006, our civil liberties score dropped to 8.24 last year.

Needless to say, this 10% drop in our civil liberties score might be traced to the President’s aggressive war on drugs which, as of January 2017, has resulted in 7,080 deaths borne by either legitimate police operations or so-called extrajudicial killings.

Indeed, the President’s drug war has received a lot of flak – domestically and internationally – because of its blatant disregard for basic human rights. Colombia’s former president has recently warned that force won’t work to fight drugs, and that “the war on drugs is essentially a war on people.”

Despite this advice – and the deeply embarrassing murder of a Korean businessman by police officers – the AFP is now awaiting the President’s go signal to formalize the creation of a battalion-sized task force to help fight the war on drugs.

Without strong and reliable checks, the resumption of the drug war with even more state-sanctioned force could spell disaster as far as our civil liberties and democratic way of life are concerned.

Conclusion: Our democracy is fragile

Perhaps it’s best to remember EDSA 1 not as one great wholesale victory for democracy, but rather as a testament to the fragile nature of democracy.

For instance, immediately after EDSA 1, the number of human rights violations and enforced disappearances did not automatically subside given the immense political upheaval that it brought. Also, EDSA 1 alone did not bring down inequality and poverty significantly. Without a more inclusive economy, it will be hard to promote political participation moving forward.

Today, the tenacity of Philippine democracy is being tested anew, what with new threats to our individual and civil liberties coming from the government, foreign powers, or even social networks. Senator Leila de Lima’s hurried arrest is one of most recent manifestations of this.

Rather than “move on” from the lessons of EDSA 1, we ought to remember that the struggle for democracy is really an ongoing project for the new generations, rather than one that our parents and grandparents finished 31 years back.

If we remain complacent, we risk bringing back a farcical, nightmarish, and Marcosian version of democracy that no Filipino today deserves to relive. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD student and teaching fellow at the UP School of Economics. His views do not necessarily reflect the views of his affiliations. Thanks to Kevin Mandrilla for helpful comments and suggestions.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.