SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Months before the 2016 presidential election that President Rodrigo Duterte won, mining industry players gathered in the ballroom of Solaire Resort in Pasay City for their annual Chamber of Mines summit.

Months before the 2016 presidential election that President Rodrigo Duterte won, mining industry players gathered in the ballroom of Solaire Resort in Pasay City for their annual Chamber of Mines summit.

It was noticeably a smaller crowd than the previous September gatherings following controversies and regulatory issues that had hit them.

Most of the topics were about technical stuff: “Tracking resource super cycle and commodity boom and busts”; “The social responsibility of the global resources sector”; “Critical pathways to sustainable development”; “Investment, hurdle rates and taxation.”

I met more lawyers, fund managers and mining consultants during the breaks than industry players themselves. Considering that the years before, more of the country’s biggest business groups have added mining into their conglomerate portfolios, the bigwigs themselves were not around: San Miguel and the conglomerates led by Manuel Pangilinan, and the families of the Sys, Consunjis, Manuel Villar, Alfredo Ramos, Tomas Alcantara, and Manuel Zamora. Some just sent their executives.

It was the calm before the storm.

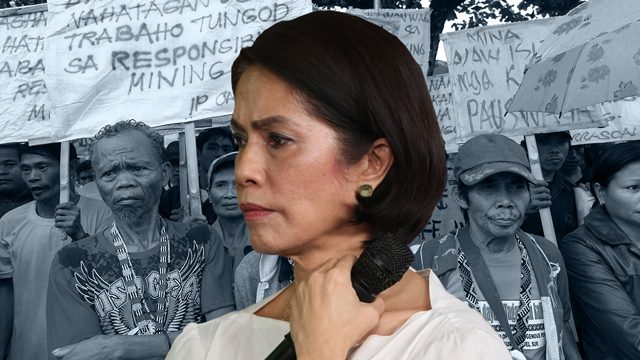

And it seems the industry did not prepare for a storm that is Gina Lopez, Duterte’s anointed environment secretary who recently dropped bombs – closures of and contract cancellations involving around 100 operating and non-operating mines all over the country.

Now the Chamber of Mines, whose several members were affected by the recent decisions of Lopez, is trying to ensure she will not be confirmed by the Commission on Appointments. (READ: Miners band together to oppose Gina Lopez’s confirmation)

Lopez has the momentum as far as public support is concerned. She has been galvanizing grassroots organizations for support during her confirmation hearings. She has been diligently doing rounds of media interviews where she preaches on the “common good” and “love for country.” (READ: What drives Gina Lopez)

She utilizes social media to reach the young, the impressionable and those in remote areas. She’s a natural on cam, and she connects to her supporters through Facebook Live, unrehearsed. “Let love and light rule the day,” she urged her viewers after her morning meditation. “You cannot build an economy based on suffering and injustice. It isn’t right,” she said in another. To the uninitiated about the mining industry, it is hard to argue with these.

She took to Facebook again to apologize after she made a baseless claim that lawmakers who are part of the confirmation committee were being bribed P50 million each to junk her. Her supporters, based on their comments on her social media posts, seem to forgive her. An environmental extremist, a yogi, and a scion of one of the country’s richest clans, Lopez looks and sounds authentic and relatable to an audience that transcends economic classes and borders. (READ: Green vs greed? The Lopezes’ new family saga)

The miners, on the other hand, have difficulty winning this battle for hearts and minds.

In preparation for Lopez’s confirmation hearings, they stick to their usual: polishing the substance of their defense. They cite sanctity of contracts, lack of due diligence, rule of law. They appeal to logic. They are surgical. They are focused on the legal battle where they are more comfortable and experienced.

Lopez wants to win the battle, but she also wants to win the war. “Let me do things that have to be done,” she said with the stubborn streak of a change agent, as she nears the start of her confirmation hearings, and amid efforts from other members of the Duterte Cabinet – finance secretary Carlos Dominguez, in particular – to temper her bold moves.

The industry has been merely reacting to her controversial pronouncements. They’ve been holding regular press conferences after Lopez has already held a press conference announcing a decision. With a common foe, the chamber members, even though they are competitors, unite and speak in one voice against Lopez, her decisions, and her confirmation as a Cabinet member.

In the many crises, both local and global, reacting to a controversy is a weak strategy. Being proactive, or preparing before the storm strikes, has long been a common lesson learned from past and similar situations. Strategists speak of the pre-crisis need to build goodwill. Risk experts’ favorite metaphor for this is building an emotional bank account that can be a buffer when the business messes up or when a controversy hits them for lack of empathy and integrity, or for being greedy, as Lopez tends to project the miners are.

The good vibes have to be built over time, before a crisis hits, so the business, or in this case, the mining industry, has a good stock of it for later.

Miners’ failure

It has been a business truism that people tend to be more willing to give the entity or business group the benefit of a doubt and are more willing to stand by that entity if it has earned enough goodwill from its stakeholders. This allows it to get through the controversy over time.

The mining industry failed to be proactive in building its goodwill on a national level.

Miners generally define their stakeholders as those that directly affect their business. “You have to judge us based on how we are rated by our host communities, how we are accepted by our host province and the surrounding areas, how committed we are to our corporate social responsibility toward our workers, our neighbors, etcetera,” one miner said as we contemplated how the industry is managing the current situation.

They planted trees, thousands of them. They worked with local governments to augment budget for social services, like education, health, housing and livelihood.

But beyond the geographic borders of their mining operations, they generally didn’t care anymore. There has been no or little investment in building goodwill to counter a possible effort by an environmentalist-turned-environment secretary to cast them as greedy capitalists.

Years with Aquino

It may seem baffling offhand why miners dropped the ball. They’ve been in similar situations in the past, after all.

The most recent example is the passage of Executive Order No. 79 during the administration of former President Benigno Aquino III, the predecessor of Duterte. This 2012 order halted the issuance of new mining contracts, causing an uproar among industry players who then got to work together to navigate the seemingly hostile environment.

Their collective action as an industry then was telling: They decided not to engage with Aquino. Instead, they prepared to wait out his term.

“We weren’t happy with him (Aquino), but there was nothing we can do. He’s the president and he’s got a fixed 6-year term, and his term was ending,” said another miner, sharing a common sentiment among chamber members.

While waiting for a new, and hopefully more friendly, president, the miners focused on their individual and current operations, not on the future concerns of the entire industry.

Commodity prices then hit their cyclical high, and the world’s top two nickel ore sources faced challenges. Indonesia banned the export of unprocessed nickel ores while Russia’s biggest nickel miner suffered sanctions. Thus, from 13th place in 1998, the Philippines became the world’s top nickel producer in 2015, accounting for a fifth of the global supply.

Global spotlight, ISO standards

Philippine miners took the opportunity to bask in the global spotlight, strengthening their finance talents who then traveled the world to explain their companies’ profit prospects and with it their stock prices.

Global media coverage of Philippine mining focused on local entrepreneurs riding this mining boom, and who has better connections with middlemen who in turn secured forward orders (a promise to buy or deliver something in the future) from Chinese and Japanese steel makers. Typhoons hitting the Philippines even meant an impact on metal prices since terrible weather affects shipment schedules.

In the meantime, the chamber members, who comprise the largest mining operators in the country, worked on securing an International Organization for Standardization (ISO) certification. Fully complying with the ISO 14001 is a badge of honor that metal miners wear to claim they are aligned with global standards in environmental management practices. The audit entailed tons of paperwork with 3rd party certifying companies, but it was a clear-cut process businessmen can follow and implement.

In fact, when Lopez was announced as the new environment secretary, the large miners mistakenly thought their ISO 14001 certifications would be enough to assure her they are responsible miners. In a television interview, the chamber’s executive vice president Nelia Halcon admitted the chamber assumed Lopez would start auditing the illegal and small-scale miners who didn’t have to follow similar strict environmental standards.

In other words, during the calm before the storm, the industry players were busy.

Beyond their own individual business interests and geographical reach, they did not invest in building goodwill for the entire industry that they can use as a buffer in case their wish for a new president who is more accommodating to the industry than Aquino has been does not happen. They remained comforted by the fact that their contracts and their contacts were intact.

Lopez, on the other hand, is of a totally different mold, and an expert in communicating her advocacies. “She is easy to sell. She understands the narrative, the undercurrent of the changing times,” said one of the communications experts who took her on as a client to help in swaying public opinion to her favor in the run-up to the confirmation hearings. Her passionate calls for change resonate with the global battlecry against the establishment and the elite that produced Brexit, US President Donald Trump, and even Duterte.

Commodities, not consumers

What the miners in the Philippines are experiencing is not unique. Industries associated with “dirty” or “sin products” – tobacco, alcohol, gambling, and coal, oil and gas extractive companies – have been there and done that.

Playing politics and the politicians or sticking to the legal battlefield has been a staple strategy, as were dirty tricks, like manipulating scientific inputs to muddle the logic and divert attention.

In the past decade, however, strategists have adopted a more forward-thinking style: Instead of attacking groups opposing their businesses, they decided to engage with a larger group stakeholders – government, regulators, communities, civil society, and other groups beyond their usual circle of influence – to help shape the discussion about them and reduce resistance. For example, alcohol groups now advocate “responsible drinking,” while casino operators trumpet “responsible gaming.”

Unlike these industries, however, miners don’t deal directly with consumers who, especially in this age of social media, can publicly complain to have a direct stake in the future of a branded product or service. Miners don’t have to advertise their product or promise product quality to consumers. Miners don’t have to care if a gold bracelet has the right cut or clarity, or if the steel produced usinng their nickel ore is strong enough to keep a skyscraper upright. They deal with traders to sell in bulk the raw materials that producers turn into an end-product. They are wired to extract resources in the most efficient ways as possible. Working to be loved by the public is not in their DNA.

“We tend to think of customers, of our business in a technical way. We don’t need to be sensitive to personal needs of people. We don’t need to be in tune with customers,” explained a miner.

Note, however, that the owners of some of the biggest mines in the Philippines have core businesses that are very much in tune with customers: The Sys who have stake in Atlas Mining and Tampakan Mining operate the country’s biggest mall network (SM Prime) and bank (BDO Unibank). Manuel Pangilinan, who heads gold producer Philex Mining which has contracts that were ordered cancelled, is into industries that we use every day – telco (PLDT), power (Meralco), tollroads (NLEx, SCTEx, Cavitex, CALAx), water (Maynilad), hospitals, sugar, and more. Businessman and former senator Manuel Villar, whose growing empire now includes the planned King-King copper-gold project, has investments in real estate (Vista Land, and Starmall), retail, water utility, education, death care and health care. The Consunjis who operate the Semirara coal mine have been actively diversifying into mid- and high-rise condominiums (DMCI Homes). Alredo Ramos of Atlas Mining belongs to the family that runs the National Bookstore chain.

The disconnect is glaring. The sooner these miners acknowledge and address it, the better prepared they are to deal with future Gina Lopezes. — Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.