SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

In April the government finally unveiled Dutertenomics as the President’s “economic and development blueprint” for the country.

At the heart of Dutertenomics is a promised “golden age” of infrastructure, which includes at least one new subway, several new railways, expressways, airports, etc.

All these projects are expected to ramp up public infrastructure spending by a whopping P8.4 trillion in the next 5 years. At this rate, infrastructure’s share to GDP is seen to increase from 5.4% in 2017 to 7.4% in 2022.

But how will we pay for P8.4 trillion? Can we really afford Dutertenomics?

In this article we explain the delicate balancing act between the 3 main financing options: taxes, loans, and public-private partnerships (PPPs).

But perhaps more crucial to the ultimate success of Dutertenomics is the President’s personal interest and involvement in the matter.

With one year already gone and future tax revenues still left hanging in the balance, it’s time for the President take charge and champion Dutertenomics himself. Otherwise, the infrastructure golden age his administration promises could turn out to be just a pipe dream.

Why infrastructure?

First of all, there are good justifications for Dutertenomics’ focus on infrastructure. Various economic studies have shown that high-quality infrastructure tends to reduce transportation costs, promote trade flows, and increase people’s incomes. In principle, the more infrastructure, the better.

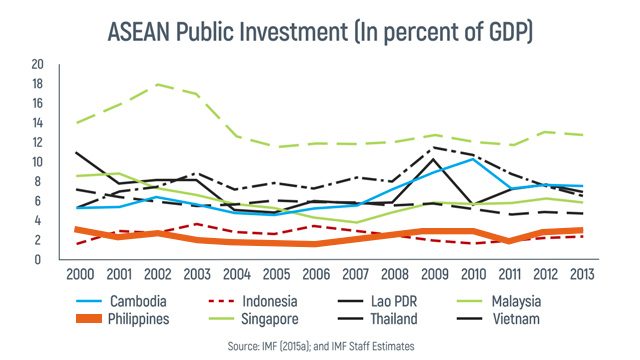

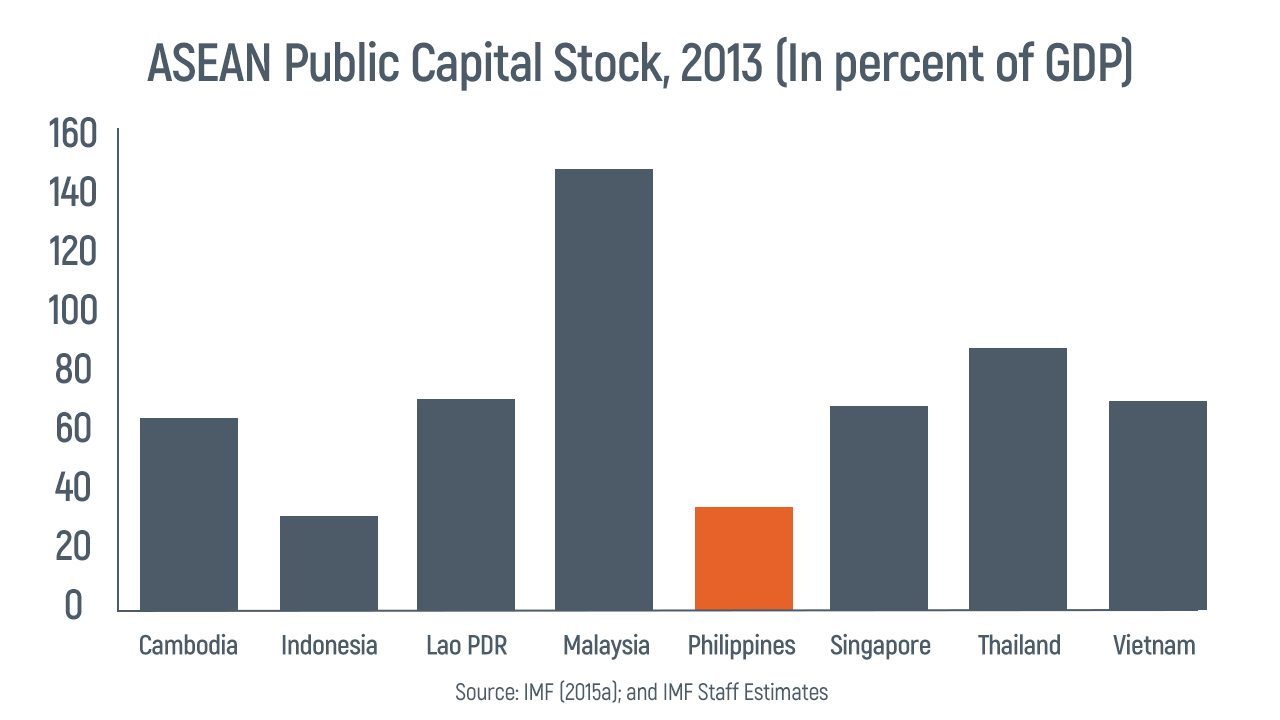

Indeed, the country’s inadequate infrastructure has constrained our growth in the past. The figures below show that the Philippines has been one of the region’s most frugal public infrastructure spenders, and this partly explains our relatively low levels of capital stock:

Needless to say, our infrastructure needs to catch up with our fast-growing economy.

But, admittedly, not all infrastructure projects will have the same impact. For instance, to reduce traffic congestion, the government must venture into “smart” infrastructure projects and urban plans that are friendlier to pedestrians than cars. (READ: Carmaggedon redux: Will building more roads solve our traffic problems?)

How can we pay for Dutertenomics?

Even with a good rationale, an infrastructure golden age surely requires massive funding. How will we ever be able to pay for it?

Back in May, a Forbes article went viral when it claimed that new loans from Japan and China, intended to fund part of Dutertenomics, will inevitably put the country into a “virtual debt bondage.”

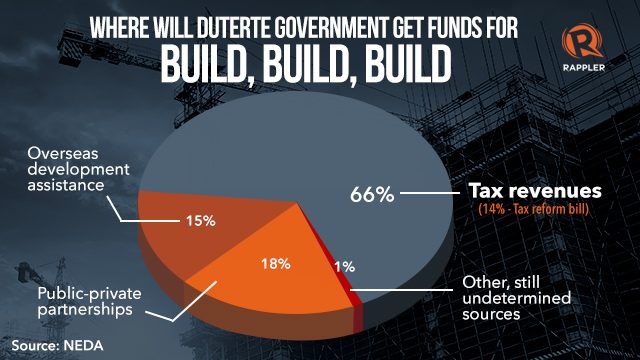

However, it turns out that official development assistance (ODA) – which comes from foreign governments and multilateral institutions – is expected to fund only 15% of Dutertenomics.

We also know from everyday experience that borrowing is not bad per se. For as long as interest rates are low, the grace and repayment periods are long, and the government exercises prudent debt management, these new loans won’t necessarily lead us to a debt crisis similar to what happened in the early 1980s.

A much larger part of Dutertenomics will be funded from taxes and PPPs. Hence, the issues surrounding these two other financing options deserve more of our attention.

Tax reform must generate sufficient revenues

Easily two-thirds or 66% of Dutertenomics’ P8.4 trillion budget is expected to be financed from tax revenues. This explains why the President’s economic managers are so intently campaigning for the tax reform measures to pass in Congress.

Recall that the tax reform bill – otherwise known as TRAIN – aims to reduce personal and corporate income tax rates. To offset the revenue losses, however, TRAIN also aims to remove long-standing exemptions and impose new taxes on petroleum products, automobiles, and sweetened beverages.

In total, the tax reform bill approved by the House is expected to raise P1.163 trillion of net revenues from 2018 to 2022.

However, this will cover just 14% of the P8.4 trillion budget for Dutertenomics. What’s more, the House’s version is expected to raise 8% lower revenues than what the finance department originally proposed.

The tax reform bill is now in the Senate, but many senators are reluctant to pass the measure as envisioned by the President’s economic managers. Many of their qualms are understandable – they can’t risk displeasing voters with the 2019 elections coming up.

However, without sufficient tax revenues, Dutertenomics could lead to successive budget deficits and mounting debt.

Budget deficits are not worrisome per se. But persistent deficits could lead to interest rate hikes and weak private investments, as well as credit rating downgrades and lower future growth. (READ: Government hits P33.4-B budget deficit in May)

Remember that it’s not just Dutertenomics that needs funding. For instance, Congress recently passed the Universal Access to Quality Tertiary Education Act, which will subsidize tuition fees in all public universities, colleges, and technical-vocational institutions. This law will require “more or less” an additional P50 billion to P53 billion yearly.

Hence, if lawmakers pass a watered down version of tax reform that generates insufficient revenues, they risk impairing the finances not just of Dutertenomics but also other big-ticket projects that they themselves enacted, like tuition fee subsidies.

With the prospect of frequent deficits and growing debt, the government should at least make sure that economic growth remains robust. Our debt-to-GDP ratio has been declining over the past decade, except in 2009, when public external debt grew faster than GDP.

A growing public debt is tolerable as long as the nation’s income is growing faster. Hence, the last thing we need now are bad, reckless, and ill-thought policies that will disrupt the country’s growth momentum.

PPPs may be faster and more cost-effective

Amid a tightening fiscal space, there’s one more way to fund Dutertenomics: PPPs. Indeed, government planners expect 18% of Dutertenomics to be funded through PPPs.

Unfortunately, the Duterte government seems somewhat averse to this mode of financing, perhaps because of previous delays and their being heavily identified with the Aquino administration. In late May, President Duterte already removed 5 regional airports from the PPP pipeline.

With so many infrastructure projects to deliver, the government could not really afford to shun PPPs. In fact, based on previous successes, PPPs may prove to be the faster and more efficient way to build major infrastructure projects. (READ: Addressing myths of PPPs)

Some officials say they prefer the “hybrid PPP” approach, where the government constructs the projects and bids out maintenance and operations later on. However, this goes at the heart of an old debate between the economics of the public and private sectors: Can the government really construct major infrastructure projects faster and more efficiently?

This question is made more crucial by the string of corruption scandals that hounded major infrastructure projects in the past, including the North Rail and NBN-ZTE deals during the Arroyo administration.

Already, red flags are up. Following President Duterte’s visit to Beijing in 2016, the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism found that some firms that brought projects home were in fact undercapitalized and inexperienced in the infrastructure sector. In a Senate inquiry, it also turned out that some of these new loans will allow the Export-Import Bank of China to name pre-qualified contractors for Philippine projects.

Because of the long-term nature of these new projects and loans, a considerable part of Dutertenomics will likely be paid for by future generations of Filipinos. Hence, if only to be fair to future generations, the government should be completely transparent about how Dutertenomics projects and contractors are chosen.

Duterte himself must champion Dutertenomics

In conclusion, Dutertenomics promises to fill our long-standing infrastructure gaps and provide a stronger foundation for future economic growth.

But to do this right, we must settle our finances first. With tax reform hanging in the balance, the government shunning PPPs, and giant loans looming in the horizon, only a thin line separates the promised infrastructure golden age from becoming a pipe dream.

Many of these financing issues could be resolved faster if the President took greater responsibility for Dutertenomics himself.

Throughout his first year in office, the President has been criticized for focusing too much on drugs and crime, while leaving crucial economic matters to his Cabinet. Indeed, many people see Dutertenomics more as the Cabinet’s initiative, and not the President’s.

However, with the executive and legislative currently in a deadlock over tax reform – and the financing of Dutertenomics hanging in the balance – the President can no longer afford to take a backseat on economic matters.

If only the President was half as involved in economic reforms as he is in the fight against drugs and crime, we could be on the road to the promised infrastructure golden age sooner than we might think. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD student at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Thanks to friends and colleagues for useful comments and suggestions. Twitter: @jcpunongbayan.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.