SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

A captain of industry in the Philippines (who will remain unnamed) once told us that the biggest casualty in the aftermath of the Marcos regime was the severe lack of ambition in our economic and development planning. He lamented that as the country dug itself out of the economic and debt disaster left by Marcos, we failed to recover enough trust in our collective ability as a nation to again take major risks with high rewards. His primary example of this was how infrastructure and other national investments have been turned into piecemeal efforts, often driven by the private sector.

Additional critiques of past infrastructure projects note how infrastructure investments disproportionately concentrated in Imperial Manila; and that the implementation of larger projects tend to be slow and prone to corruption.

President Rodrigo Duterte’s “golden age of infrastructure” could dramatically change this, by ramping up the ambition in both the scope and scale of infrastructure projects in the country. Yet with increased ambition, could there also be more risk?

Infrastructure: DU30 vs PNoy

In this article we analyze 3 possible change parameters. Do the Duterte projects reflect greater size and scope? Do these projects now prioritize long neglected regions in the country? And finally, do they match ambition with governance?

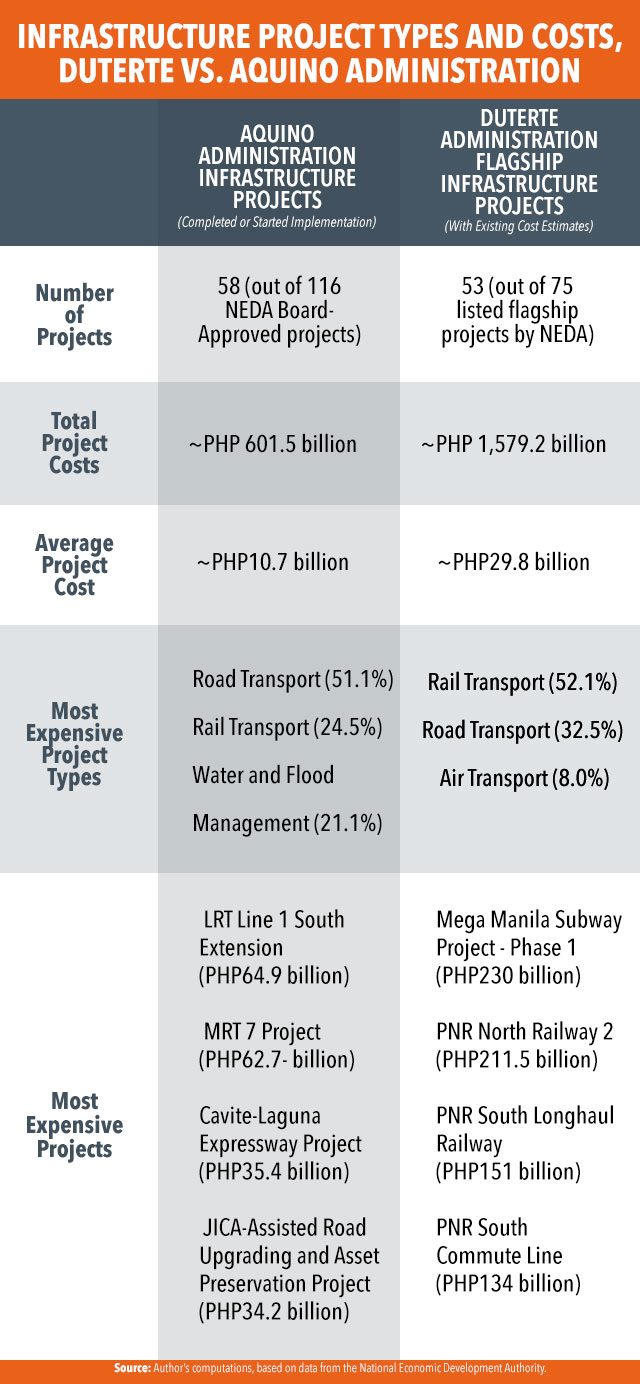

We undertook a preliminary analysis of infrastructure projects under both the Duterte and Aquino governments, based on data from the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA). For this, we compared the Duterte administration’s NEDA-listed flagship projects with available cost estimates, with NEDA Board-approved infrastructure projects whose implementation had either begun or had been completed under the administration of former president Benigno Aquino III. Projects whose implementation had not started by the end of Aquino’s term, or which were discontinued, were not included.

Our analysis covers 53 flagship projects of the Duterte administration with cost estimates, and 58 NEDA Board-approved projects under the Aquino administration. While 15 projects approved under the Aquino presidency were also counted among Duterte’s flagship ventures, the trends we discuss still hold whether or not these projects are included in our analysis of the Duterte government’s priority infrastructure initiatives.

Most of the Duterte administration’s projects are still in the pipeline, while those of Aquino are already completed or underway, so the analysis is preliminary. Much can still change. Yet already the emerging picture suggests a large difference in infrastructure patterns across the Aquino and Duterte administrations.

Big is beautiful?

The total expected spending requirements of Duterte’s planned flagship projects are already around P1.6 trillion, whereas that for the Aquino government was only about P600 billion (Table 1). When focusing on individual projects, the estimated cost of the average Duterte flagship venture is nearly 3 times (P30 billion) than the infrastructure projects under the Aquino presidency (P11 billion).

While the Aquino government channeled significant resources to sub-regional road and rail transport initiatives (51.1% and 24.5% of total costs), such as the MRT7 and the Cavite-Laguna Expressway projects, as well as major investments in water management infrastructure (21.1%), the Duterte administration, on the other hand, has prioritized larger region-linking transport projects.

More than half of all flagship project costs (52.1%) under Duterte are focused on rail transport alone, with the 4 most expensive items in the list coming from railway projects that will span several regions. For example, the P230-billion Mega Manila Subway Project, upon full development, is intended to serve not just NCR, but also key suburban areas in Bulacan and Cavite.

Duterte’s road and bridge initiatives – at 32.5% of anticipated big infrastructure spending – include planned “mega bridges” from Bohol to Leyte, Luzon to Samar, Cebu to Bohol, Leyte to Surigao, Mindoro to Batangas, Camarines Sur to Catanduanes, and Panay, Guimaras and Negros. For a rough comparison, perhaps only the San Juanico bridge connecting Samar to Leyte approximates the scale of these pipelined bridge projects.

Imperial Manila is still the big winner?

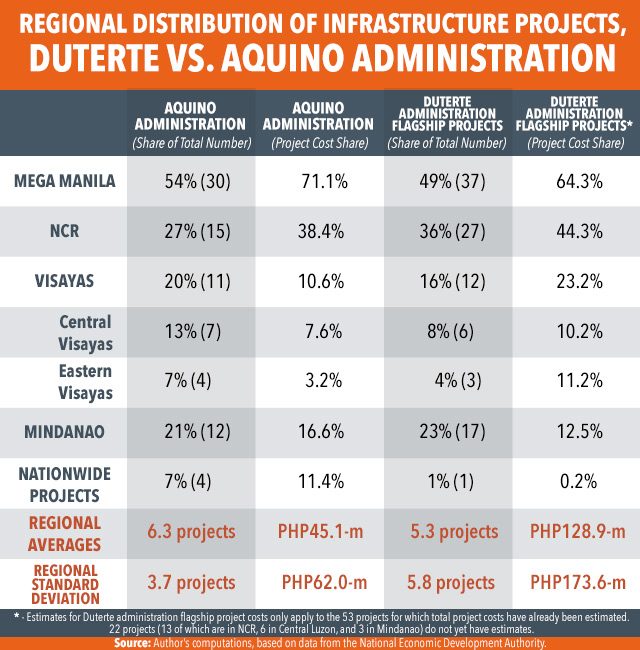

Though the Aquino administration embarked on relatively smaller projects, these were nevertheless more evenly spread across the country. Under Aquino, a significant share (11.4%) of the NEDA-approved projects involved nationwide infrastructure programs, while regions across the country received an average of 6.3 projects each (see Table 2).

Duterte’s flagship projects, however, do not seem to break from a “Manila-centric” pattern. In fact, the opposite seems to have occurred: nationwide infrastructure programs have shriveled to a mere 0.2% of total expected spending, even as regional gaps in big infra investments have expanded.

Should Duterte’s flagship projects be implemented as presently listed, the average number of projects will actually fall to 5.3 projects per region, even while the standard deviation (a basic measure of statistical dispersion) of estimated infrastructure spending across regions will grow to nearly 3 times that of the Aquino administration’s.

Moreover, of all the regions in the country, NCR is the only area nationwide which will decisively increase its share of the total number of infrastructure projects from the Aquino to Duterte administration (from 27% to 36%). Similarly, its stake in expected spending will rise from an already disproportionate 38.4% of big infrastructure costs to an even higher 44.3%.

It is important to note here that we are not making a judgement on the appropriateness of these proposed investments for addressing the Philippines’ infrastructural dilemmas. Similarly, we stress that the regional distribution of projects can still change considerably in the months ahead – 22 flagship projects have yet to receive cost estimates (though 13 of them are also in NCR), while trillions of pesos worth of non-flagship infrastructure projects that will be in NEDA’s broader Public Investment Program (PIP) for 2017 to 2022 have yet to be accounted for.

Aid or foreign policy instrument?

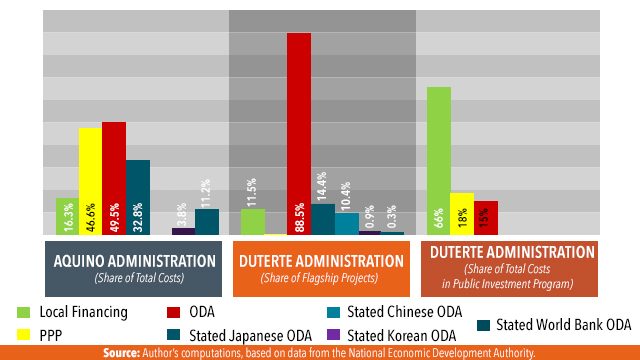

As noted in our earlier analysis, a heavy emphasis on government-led projects seems to be in the works. According to previous NEDA statements, the Duterte administration’s PIP for 2017 to 2022 is to be financed mainly by government funds (66%), and augmented by public-private partnerships (PPP’s – 18%) and overseas development assistance (ODA – 15%).

But if we scrutinize the flagship figures more closely, the bulk of Duterte’s priority mega-projects will be financed by ODA and foreign sources (88.5%). Only 2 out of the 75 flagship projects under the Duterte administration are expected to be financed through PPPs so far, even though these same two projects have yet to receive any cost estimates. This represents a significant change in funding strategy compared to NEDA-approved infra projects whose implementation had begun under Aquino, where ODA and PPPs financed roughly 49.5% and 46.6% of all project spending respectively.

Yet even among the sources of ODA financing there has been a major shift: while Japanese ODA covered 32.8% of the financing under Aquino, it has been trimmed down to only 14.4% under Duterte. On the other hand, Chinese ODA has already been ratcheted up to 10.4%, from practically zero during the previous administration.

In the months ahead, it is still possible that the share of Chinese financing could increase further: more than 60% of Duterte’s flagship infra spending slated for ODA financing has yet to be assigned a specific foreign funding source, while the funding strategy for another 11 flagship projects without existing cost estimates has yet to be declared by the government.

De-emphasizing PPPs and ramping up ODA raises some red flags where Chinese ODA is concerned. Chinese lending to and investments in Latin American countries like Venezuela, for instance, were not concessional; and these were indexed on commodity prices which left this country (and other borrowers like it) vulnerable to commodity price swings. The bulk of Chinese investments also involve state owned enterprises (SOEs) which raise additional concerns linked to national security, particularly where critical telecommunications and major transport infrastructure is concerned.

Moreover, Chinese investments have been known to produce white elephants even in their home country. Perhaps one of the reasons is that these projects promote Communist Party policies and goals, and are less disciplined by market forces. Understandably, there is concern regarding their financial viability – in turn signaling risks shared with partners who engage them.

Already in the Philippines, investigative research on the flagship investments of the Duterte government targeted for Chinese financing raise concerns over the lack of expertise and shallow track records of the parties to these deals, as well as high risks of rent-seeking and corruption.

Given the scale, costs, and risks involved, the stakes on the “golden age of infrastructure” have become too high to leave to the government. In the days to come, the broader Filipino public must organize and exercise vigilance to ensure that our nation’s long-term interests will be best served by the Duterte government’s infrastructure program. Since many of these projects are likely to spill over to the next administration due their scale, it should be among our foremost public priorities to build apolitical, multi-stakeholder coalitions to help ensure strong buy-in, as well as the smooth and accountable implementation of these projects. – Rappler.com

Ron Mendoza is the Dean of the Ateneo School of Government (ASOG). Jerik Cruz is an economist with the Ateneo Policy Center. The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect those of the Ateneo de Manila University.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[PODCAST] Beyond the Stories: Ang milyon-milyong kontrata ng F2 Logistics mula sa Comelec](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/11/newsbreak-beyond-the-stories-square-with-topic-comelec.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Free to disagree] How to be a cult leader or a demagogue president](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/TL-free-to-disagree.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] Can Marcos survive a voters’ revolt in 2025?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-voters-revolt-04042024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=251px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Edgewise] Quo vadis, Quiboloy?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/quo-vadis-quiboloy-march-21-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] Sara Duterte: Will she do a Binay or a Robredo?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/tl-sara-duterte-will-do-binay-or-robredo-March-15-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.