SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Some 27 years after the “EDSA People Power Revolution” that toppled the Marcos dictatorship in 1986, clan politics continues to thrive in the Philippines. In recent months, members of some prominent political clans jointly filed their candidacies at the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) for various positions up for grabs in the May 2013 elections.

Some 27 years after the “EDSA People Power Revolution” that toppled the Marcos dictatorship in 1986, clan politics continues to thrive in the Philippines. In recent months, members of some prominent political clans jointly filed their candidacies at the Commission on Elections (COMELEC) for various positions up for grabs in the May 2013 elections.

There has been increasing awareness of how political dynasties appear to be proliferating in the country; and motivations for countering them vary. Some argue that political dynasties run counter to the Philippine Constitution, which contains a clause against dynasties in elected office, but lacks an enabling law to give it teeth. Still others warn against the monopolization of political power, with pernicious side effects ranging from promoting patronage-based and traditional politics, consolidating the monopoly of power over politics and the economy among a few families, to crowding out other potential leaders of less well-known pedigree but of equal if not greater capabilities.

Where do dynasties thrive?

Our initial study, recently published in the Philippine Political Science Journal, is one of the first empirical analyses of political dynasties in the Philippine Congress. The main findings of this study suggest that:

- About 70% of the 15th Philippine Congress is dynastic; and dynasties dominate all of the major political parties.

- On average, there are more dynasties in regions with higher poverty, lower human development and more severe deprivation;

- Roughly 80% of the youngest Congressmen (ages 26-40) are from dynastic clans;

- Dynasties tend to be richer (higher SALNs) than non-dynasties, when one excludes a famous boxer turned Congressman who is presently pulling up the average wealth of the non-dynasties. (Nevertheless, that outlier appears to be busy creating a dynasty already so after May 2013, he may yet pull up the average wealth of the dynasties as well.)

As I mentioned in an earlier article I wrote on this, what causes concern here is that political dynasties in the Philippines thrive in regions with relatively higher poverty, lower human development and more severe deprivation. Our initial study does not yet allow us to conclude causality, but the two competing explanations already paint a worrying picture. Either poor people continue to vote for political dynasties, or dynasties continue to frustrate poverty-reduction efforts. And as I have argued before, neither of these explanations is palatable for most of us who long to see development accompany democracy.

A democracy is supposed to empower the poor and low income groups—in effect de-concentrate political power which would otherwise be the case in a non-democracy. Yet this does not seem to be what is happening in the Philippines. Even if we “just let the people decide” as one dynastic politician urges, there are often not many options placed on the table. In many Philippine provinces, dynastic politicians run unopposed or are opposed only by other dynastic politicians. There is not much of a choice if clan politics effectively monopolize the system.

A democracy is also supposed to possess strong checks and balances in the governance of the public sector, yet even here, dynasties may also be creating severe contradictions within democracies. To examine this angle, my colleagues and I are now following up with another study that tries to differentiate fat (“sabay-sabay” or all at the same time) vs. thin (“isa-isa lang” or one at a time) dynasties at the local government level, recognizing the reality that some dynastic clans do not just hold on to particular positions over time, but have begun to simultaneously occupy multiple elected positions in certain parts of the country.

Dynasties of all shapes and sizes

In our recent mapping of political dynasties in Philippine provinces, with a focus on Governors, Vice-Governors, Mayors, Vice-Mayors, Congressmen and Provincial Board Members, Dinagat Islands, Siquijor, Maguindanao and Ilocos Sur top the list with some of the largest clans:

- In Ilocos Sur, Luis Chavit Singson is the incumbent Governor. One of his sons, Congressman Ronald Singson was convicted of drug possession and evicted from office, and another son, Ryan Singson took over the Congressional seat vacated by Ronald. Ryan is now running for Governor to try to take over from his father. Ronald is also running for office despite the conviction

- In Siquijor, Congressman Orlando Fua has several sons in office, including Orlando Jr. who is the incumbent Governor (now running for Congressman), Orville who is in the Provincial Board and is running for Governor (to try to take over from his brother), and Orpheus who is an incumbent Mayor

- In Dinagat Islands, Glenda Ecleo is the incumbent Governor, while daughter, Geraldine Ecleo Villaroman, the incumbent Vice Governor, is running against her mother for Governor this May. The daughter claims to be doing this to try and curb the excesses of her family’s dynastic hold on the province .

In addition, dynasties in Maguindanao offer an illustration of what political dominance might look like. The Ampatuan clan still wields significant power in that province despite the detention of the family patriarch, Andal Ampatuan, and some family members who are accused of the murder of 58 people, including the wife of political rival, Esmael Mangudadatu and numerous media personnel.

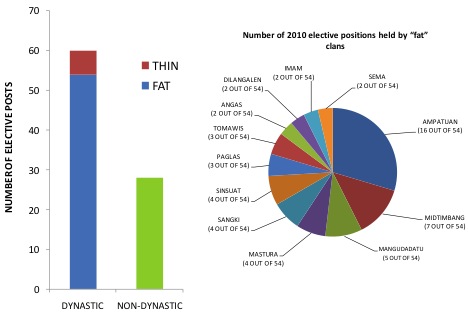

On analysis of the key positions in this province, 60 of 88 positions are held by dynastic officials, 54 of which are held by officials from “fat” clans (and a mere 6 from “thin” dynasties). A “fat” dynasty has more than one member occupying positions in 2010, or has at least one member who occupied a position in 2007. On the other hand, a “thin” clan has only one official in 2010 and has at least one member who occupied position in 2007. Among the “fat” clans in Maguindanao, the Ampatuans have the largest number of elected officials in 2010 (16 out of the 54 elective posts held by “fat” clans) followed by the Midtimbangs (7 out of 54 elective posts) (see figure 1).

Some observe that the proliferation of these “fat” dynasties is what triggered the recent strong interest in the Philippines to curb dynasties. Imagine a governor that could help allocate resources for several projects benefitting several Mayors in her province. Bargaining typically ensues in such situations, and one hopes some sense of what’s best for the entire province guides the final outcomes. But what if one of the Mayors is the Governor’s relative? It is easy to imagine outcomes that are detrimental to the public good, but perhaps beneficial to the continued reign of the dynastic clan. Indeed it is now common practice for politicians to funnel most of their pork barrel funds into their own bailiwicks, often prioritizing local government units and foundations controlled by relatives and allies, instead of being guided by poverty reduction and human development needs.

Local government is in many ways the front line of the public sector—where people will most feel the impact of “matuwid na daan”. Ultimately, promoting high and inclusive growth will continue to be elusive if governance and public sector management at the local government level continues to malfunction in these ways. And as evidenced by our study, the poorest regions of the country may end up paying the price for this.

The author is an Associate Professor of Economics at the Asian Institute of Management and concurrently serves as the Executive Director of the AIM Policy Center. The author thanks David Yap and Charles Siriban for their helpful inputs in crafting this article. The views herein do not necessarily reflect those of AIM. On 7 March 2013, the full results of the follow-up study will be released at an event co-organized by AIM Policy Center, Ateneo School of Government and UP National College of Public Administration and Governance. Further information could be obtained by writing to policycenter@aim.edu.

Click the links below for more opinion pieces in Thought Leaders:

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.