SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

I was 17 years old and a sophomore at the University of the Philippines when the country descended into the long night of martial law, a period in our history that would last more than a decade but leave a lifetime of scars and memories.

I was 17 years old and a sophomore at the University of the Philippines when the country descended into the long night of martial law, a period in our history that would last more than a decade but leave a lifetime of scars and memories.

One evening in September 1972, a group of students, including my dormitory mates and I, gathered on campus to protest, among others, the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus. Ferdinand Marcos took this extraordinary measure to allow the arbitrary arrest and detention of his enemies and critics in 1971, after bombs exploded at the opposition rally of the Liberal Party in Plaza Miranda. The security of the state was stake, Marcos had stressed.

Hardly had we started to march when someone announced, using a megaphone, that we had to disperse because martial law had already been declared. We did not have enough time to digest what this all meant except that we knew it was a scary thing, that the military could go after us innocents whose only crime was to speak our minds. Fear gripped us as we scampered to our dormitories.

We hurried to our rooms, passed the word that the country was under martial law, and waited for news. The air was heavy with dread and apprehension. We did not know what to expect.

Could the soldiers come in the middle of the night and pick up the activists? A number of us were not part of any radical student organization but some of our friends belonged to militant groups. What we shared in common, though, was our opposition to repression and the slide to strongman rule.

After a sleepless night, UP was eerily quiet. The university where, just a year before, the rage of the First Quarter Storm exploded, was silent. Images of students who occupied the campus, barricaded themselves, and threw Molotov bombs at the police seemed to belong to a distant past.

That morning after marked the beginning of the silencing of our freedoms, the end of decades of our democracy, noisy and freewheeling as it was. Marcos stole the rights and privileges that we took for granted. He shut down the media that were critical of him, sent his opponents to jail, where many were tortured, and made the Philippines into a Stepford-Wives republic. He wanted submission—and frighteningly so—such that those who refused either ended up in prison or disappeared.

Marcos diaries

Fast forward to the 1980s. Sometime after graduating from UP, past a few government jobs, I became a journalist. This was during the twilight years of Marcos, after Ninoy Aquino was assassinated in August 1983. Martial law was supposedly no longer in effect because Marcos had lifted it, but only in name, in 1981.

The rubber-stamp Congress, known then as the Batasang Pambansa, continued to be in session. The Supreme Court was under Marcos’s leash and the press remained shackled as state censorship was the norm.

However, a few anti-establishment newspapers, or what Marcos liked to call the “mosquito press,” were allowed as a concession to the US and the international community which was closely watching the human rights violations in the Philippines, post-Aquino assassination. My newspaper, Business Day, belonged to the independent press, which, while critical of Marcos, kept a sober tone.

I never got to meet Marcos and only kept track of him through his pronouncements. With a controlled press, it was hard to get to know the comings and goings in Malacañang Palace and, more importantly, what went on in the dictator’s mind.

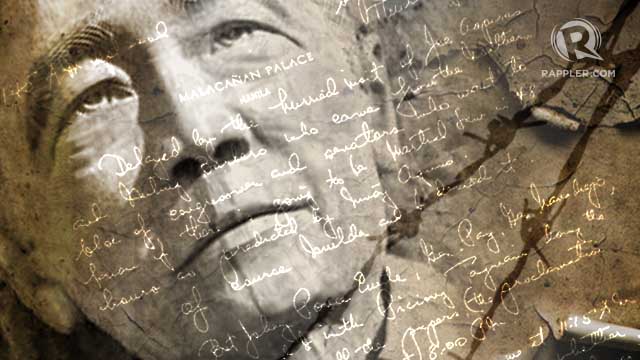

It was only recently, in the course of a research, that I got hold of the famous hand-written Marcos diaries which are over 2,000 pages long. Much has been written about these but it is worthwhile to return to the authoritarian ruler’s musings as he planned to plunge the country into its darkest years.

Here’s a glimpse of how Marcos read the national situation:

Sept.18, 1971

There are several thoughts that have nagged and battered me for the past several days:

1. The media—with the possible exception of Bulletin and Herald, they are still hewing to the communist and the radical propaganda line—Everything Marcos does is wrong.

The communists are still succeeding in distorting…

2. There are some officers and men in the AFP that are not enthusiastic about the suspension of the privilege of the writ.

3. While the majority of our people do not want a revolution, they are quiet.

4. The communist front organizations are still active. Apparently, the second echelon of leaders have taken over while their first echelon were either arrested or went underground.

Sept. 19, 1971

…The suspension [of the write of habeas corpus] is aimed at the legal cadres more than the communist army openly fighting our troops. This latter type we meet in standard military fashion—with force. The legal cadres are supposed to be neutralized by incarceration until the danger is over.

What worries me is this kind of journalism which masquerades as a sincere accurate presentation. It is worse than the openly hostile kind.

The early suspension of the privilege of the writ may have prevented what happened in 1950 when Pres. Quirino waited for the Huks to grow into a strong fighting force of 14,000 even before he proclaimed the suspension.

Today, the organization of the subversives can be shattered before they become stronger.

A year later, here’s how it happened:

Sept. 18, 1972

We finalized the plans for the proclamation of martial law at 6:00 PM to 10:00 PM with the SND [secretary of national defense], the Chief of Staff, major service commanders, J-2 [intelligence], Gen. Paz, 1st PC Zone Commander, Gen. Diaz and Metrocom commander, Col. Montoya—with Gen. Ver in attendance.

They all agreed the earlier we do it, the better because the media is waging a propaganda campaign that distorts and twists the facts and they may succeed in weakening our support among the people if it is allowed to continue.

So after the bombing of the Concon, we agreed on the 21st without any postponement.

We finalized the target personalities, the assignments and the procedures.

Sept. 22, 1972 (Note: Marcos signed the order for martial law on Sept. 21, 1972 but made it public 2 days later.)

Sec. Juan Ponce Enrile was ambushed near Wack Wack at about 8:00 PM tonight…

This makes the martial law proclamation a necessity.

Sept. 23, 1972

Things have moved according to plan although out of the total 200 target personalities in the plan, only 52 have been arrested, including the three senators, Aquino, Diokno and Mitra and Chino Roces and Teddy Locsin.

At 7:15 PM I finally appeared on a nationwide TV and Radio broadcast to announce the proclamation of martial law, the general orders and instructions.

Today, 41 years later, we remember this gloomy and foreboding moment and we say, never again! – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.