SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

With Philippines President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino now more than 2/3 of the way through his term, he can no longer be described as the “new hope” of the Philippines.

And indeed, much of the hope that his election had brought to the nation may well have faded by now given recent popularity polls. Aquino’s plight and success and that of the nation to date, detractors aside, might also offer up some thoughts for a new leader to the west, namely recently elected Narendra Modi in India.

Like Aquino, Prime Minister Modi won election in part with his calls to clean up government. Aquino had been elected president in 2010 on promises to tackle widespread corruption and massive poverty. He though has seen his popularity ratings slide amid graft allegations, a spending scandal and 3 impeachment complaints. All this and more have been robustly covered by the Philippines’ free press, from newspapers to broadcast television to social media.

How likewise fitting for the world’s largest and perhaps most free-wheeling democracy that is India that just some four months after Modi was sworn into office, critics and supporters alike are already vocally weighing in through media commentary on his performance and unconventional style.

Indeed, as fellow BRIC nations Brazil and Russia falter economically, and China faces challenges of its own, it is understandable that some business leaders are reassessing the opportunity that India has long offered, just as as Aquino brought new attention to the Philippines opportunity.

Hope remains high that Modi will bring change to his traditions-bound nation, but as Russell Green, a former U.S. Treasury attaché to India and Clayton Fellow at Rice University’s Baker Institute, puts it, “[Modi] has yet to explain his big economic reform vision in enough detail to revive corporate investment and pull the public onboard.”

It is of course too early to meaningfully judge Modi’s long-term impact. Here though are several key benchmarks by which global investors and India’s citizens should measure the country’s new leadership, just as Filipinos may well be assessing Aquino in these areas as they look to the future:

Job creation

With 50% of India’s population under the age of 30, job creation must be foremost in the minds of the nation’s leaders there as it is also in the Philippines, home to now more than 100 million Filipinos. Nothing, after all, is more dangerous than educated, unemployed youth roving the streets, their frustrations rising and, sooner or later, finding expression in public disharmony. It is estimated that a million job aspirants enter the India labor market each month. Economic growth will have to keep pace with this reality, and Modi will be wise to focus on agricultural and education reforms, vocational, technical and professional training, and a continued opening of the economy to help drive job creation and growth.

According to India’s Labour Bureau’s “Third Annual Employment & Unemployment Survey 2012-13,” the nation’s unemployment rate among “educated youth” was19.4 per cent in 2011-2012 and increased to 32 per cent during 2012-2013.

Corruption

India has adopted the institutional structure of a modern democratic state; now it is important to ensure these institutions function in an honest and credible manner. In the recent past, governance has weakened, and institutions have been hollowed out by corruption and rendered dysfunctional in India. If the public cannot trust the judiciary, or have faith that the police force works in their interest, they will resort to unfair means to achieve its goals.

If business, domestic and foreign, are to invest in the India described so eloquently on India’s independence day at the Red Fort by Modi, he must address head-on a plethora of issues that relate to the high level of corruption and poor governance, which keep the nation low on the ranks of the World Bank’s annual Doing Business survey. (India dropped from 131 to 134 in the latest World Bank ranking of 189 economies.)

After all, if no one gets punished for wrongs when evidence is clear, documented and apparent, it can only lead to a disregard for the very institutions without which a modern democratic state cannot survive. Such was the hubris among the elite and powerful that they could subvert any law or regulation merely by calling on those who had the power to protect them. Filipinos might also again be thinking of their own nation and ongoing anti-corruption efforts and hearings when reading this.

Infrastructure

From our perspectives based on our time at the Asian Development Bank, insufficient change has come to India’s core infrastructure despite hundreds of millions of dollars from numerous development agencies and banks. We might also say the same for not insignificant parts of the Philippines. In the India of today, much like the India of yesterday, even in urban areas access to water and to reliable electricity cannot be counted on. Grandiose promises already have been made by the prime minister, which would require an investment of $2 trillion, but details are sparse, and no one has articulated where the capital would come from.

Toilets on a per capita basis are deplorably low; many rivers are little more than sewers and school children cannot do their homework because there is no power in the evenings. Health and morbidity directly affect productivity; human dignity is the basis for building a cohesive society that thinks for the nation, not just for itself.

Socioeconomic divide

An urgent task awaiting the new government is the need to build cohesion out of diversity. The Muslim population of India is close to 15% and this community is a vibrant part of India. Yet, on every economic and social measure, this segment of the population ranks low. While the reasons for this are complex, the reality of their weaker economic and political power has rendered many disgruntled and with a sense of being marginalized.

Again, as we write this of India, we also think of the Philippines and the ongoing pursuit of peace and development in Mindanao.

The new government in India must focus on the Muslim community’s grievances and demonstrate an approach that is inclusive and credible. One can always believe in one’s virtue; what counts is that others believe in you. Governments are often defined by their failures, and given what was seen by many as anti-Muslim rhetoric during the Modi campaign, real progress in addressing this community’s specific needs, as part of an “all India” economic drive can help prove naysayers wrong.

In India, democracy defines itself by its ability to “get the government.” The Modi government should continue to bear that in mind as it moves forward to manage, if not meet, the incredible expectations that its election has engendered among not just foreign business leaders but its own people.

That challenge is also one that the Philippines still faces some 4 years after its last election. – Rappler.com

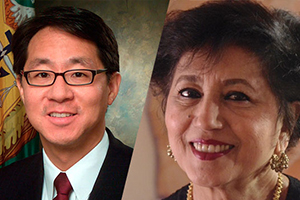

Curtis S. Chin, a former U.S. ambassador to the Asian Development Bank, is senior fellow, Asia, at the Milken Institute and a managing director of advisory firm RiverPeak Group, LLC. Meera Kumar, a former staff member of the ADB, is a New York-based freelance writer and communications consultant. Follow Curtis on Twitter at @CurtisSChin and Meera at @MeeraKumar212.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.