SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Amidst the whirlwind of summits taking place in Asia and Pacific these two weeks, there has been no escaping the persistent divisions and disagreements that continue to haunt our region.

China’s disputes with the Philippines and 3 other Southeast Asian nations over islands and islets in the South China Sea aka the West Philippines Sea, and ongoing sectarian tensions in Myanmar over the plight of the persecuted Rohingya minority are just two examples. The difficulties in moving beyond the legacy of Asia’s troubled history was perhaps summed up best in a photo from the APEC summit, featuring grimacing Chinese and Japanese leaders shaking hands.

How ironic, or fitting, that the range of high-level meetings – APEC, ASEAN, EAS and G20 summits – played out just as Germany marked the 25th anniversary of the Berlin Wall’s fall and voters in the United States delivered a more evenly divided Washington via midterm elections that will put the US legislative branch fully in the hands of the Republican Party. What a time it has been for division, past and present.

Just a few days after his party lost control of the US Senate in what has been termed a Republican wave sweeping aside numerous incumbent Democratic leaders at national, state and local levels, US President Barack Obama traveled to here in Asia for summit meetings in China, Myanmar and Australia. Unequal economic growth, climate change and sputtering efforts to strengthen cross-Pacific trade are all on the agenda.

Perhaps though the fall of the Berlin Wall and the reunification of Germany against seemingly insurmountable odds offers hope for a politically divided Washington or an Asia increasingly split over territorial issues amidst China’s rise.

The United States could well face two years of political gridlock under the watch of a weakened Democratic president and a US Congress under Republican leadership. What that might mean to the so-called US pivot, or rebalance, to Asia is still to be determined.

A divided Washington also might not bode well for those seeking greater China-US cooperation and strengthened international engagement by the United States, as attention in that country understandably shifts to key domestic issues of concern to the American voting public.

The US electorate’s support for efforts to increase the minimum wage paid to workers in some states, a policy position more often associated with Democrats, though also suggests an opportunity for America, Asia and large parts or the world, including the Philippines to come together on policy action on one area: addressing a growing divide between the rich and the poor.

According to a recent Pew Research Center 2014 Global Attitudes Survey, despite long-term optimism that exists in many nations, widespread concerns about inequality continue. Majorities in all 44 nations polled, including China, Japan, Korea and Thailand in Asia, as well as Germany and the United States, say the gap between rich and poor is a big problem facing their country, Majorities in 28 nations ranging from France to India and Pakistan say this gap is a very big problem.

Often removed from the reality of persistent poverty, political leaders whether in Berlin, Manila or Washington should take such data to heart and come together on practical policy approaches. As for which Asian nation or region is the most ‘unequal’ when it comes to the ‘Gini’ index, a common measure of income inequality, the answers can be surprising.

According to the CIA World Fact Book data, Hong Kong tops the list for having the most unequal distribution of family income in Asia – perhaps no small factor in the city’s ongoing unrest. That means the gap between the average richest and poorest families in Hong Kong is the largest in the region. This special administrative region of China ranks 12th “most unequal” out of some 141 places ranked.

Papua New Guinea (17), Sri Lanka (22) and China (27) are deemed the next most unequal places in Asia and the Pacific. The United States ranks 41st. The most equal place in the world when it comes to distribution of average family income is Sweden. The top five most unequal places are all in sub-Saharan Africa: Lesotho, South Africa, Botswana, Sierra Leone and the Central African Republic.

While such rankings are reliant on the availability and accuracy of underlying data – and indeed some governments including China have been reluctant in the past to share such data openly – examples exist in every nation of the gap between rich and poor.

One need not contrast the extreme wealth of America’s and Asia’s richest families with those of its poorest – or go back to a divided Berlin of some 25 years ago, before the fall of the Wall – to understand that a divide exists between the haves and the have nots, and between those with connections, and those with none at all. This is as evident in Metro Manila as it is in Mindanao.

Asia and the Pacific remain home to two-thirds of the world’s poor. An estimated 1.6 billion people still struggle on less than $2 a day in the region, according to the Asian Development Bank. Approximately 700 million live on less than US$1 a day.

Two billion people in the region lack access to improved sanitation, 850 million lack access to safe drinking water and one child in 20 dies before reaching the age of five. Ethnic and religious minorities and indigenous peoples are often marginalized and excluded from Asia’s continuing growth.

That too is the unequal fate of all too many people in the Asia of today. Certainly there is more to a nation, or a region or a market than its Gini coefficient. China, this year’s APEC summit host, is justifiably proud in pointing to GDP figures and showcase infrastructure projects, even as its own growth rate has slowed. If poverty is reduced overall, some leaders note, perhaps widening inequality can be justified.

Asia as a whole has enjoyed tremendous growth these past decades and has much to be proud of. Some of this was on show at APEC. The world should welcome Asia’s rise, including China’s success in lifting hundreds of millions out of poverty. But so too on show were the consequences of growth, often unequal, as Beijing also took steps to remove cars and close factories so as to reduce the pollution that too often plagues China’s capital city. Underscoring Asia’s unequal rise, Myanmar, this year’s venue for the East Asia summit, is a showcase for an economy gone wrong.

Perhaps more important than official Gini rankings are trends and attitudes as to whether or not things are unequal or getting better, and whether everyday individuals have the opportunity to succeed and to get ahead. The “genie of inequality” in the United States and Asia, including the Philippines, has long been out of the bottle. Now, business, government and civil society, and all citizens – regardless of the state of a nation’s democracy – should also think through what matters most about inequality.

In doing so, they may well find that whether driven by unequal access to education, electricity, water and sanitation, or other public services, inequality of opportunity is too often at the root of an inequality of results. This past two weeks, a united Germany celebrated the fall of the Berlin Wall, and many will marvel at the transformation of the one-time East Germany. Others may well focus on the persistent divide between the haves and the have nots.

Whether once separated by physical walls or split by existing political ones, today’s leaders in Asia, the United States and Europe – including newly elected members of the US Congress and the Philippines’ own elected leaders – should also think about how much has been and can be accomplished when barriers come down, and engagement flourishes.

At ceremonies this week, German Chancellor Angela Merkel said the fall of the Berlin Wall “showed that we have the power to shape our destiny and make things better.” Powerful words – and leaders from Washington to Beijing, Manila to Sydney, and all points in between should take them to heart. – Rappler.com

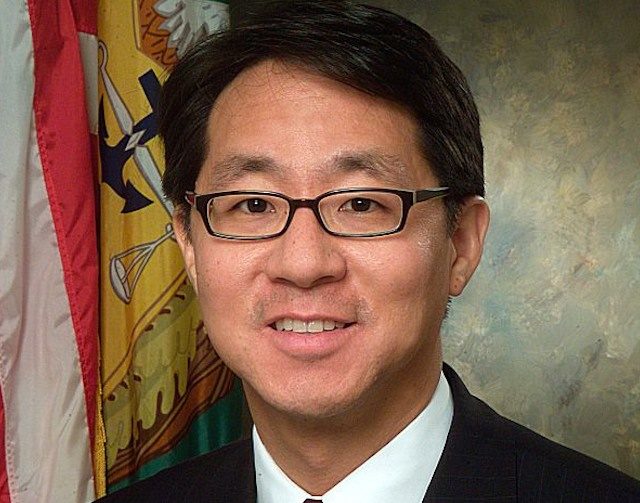

Curtis S. Chin, a former US Ambassador to the Asian Development Bank, is managing director of advisory firm RiverPeak Group, LLC. Follow him on Twitter at @CurtisSChin.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.