SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Bank have joint estimates on child malnutrition using three indicators of malnutrition: underweight, wasted or stunted.

When a child’s weight is below three standard deviations from the median weight-for-age, the child is said to be severely underweight, while if the weight is lower than two standard deviations from the growth standard but higher than three standard deviations, then the child is moderately underweight. Similarly, (moderate and severe) wasting and stunting are defined in terms of the WHO child growth standards on weight-for-height and height-for-age, respectively.

While there is clear progress in reducing child malnutrition, with stunting among children (below five years of age) dropping from a third (in 2000) to a fourth (in 2013), the magnitude of children under five with stunted growth is still high. As of 2013, this corresponds to 161 million children, seven percent of whom live in Asia. In addition, in 2013, there were 51 million children under 5 years that were wasted, while 17 million were severely wasted.

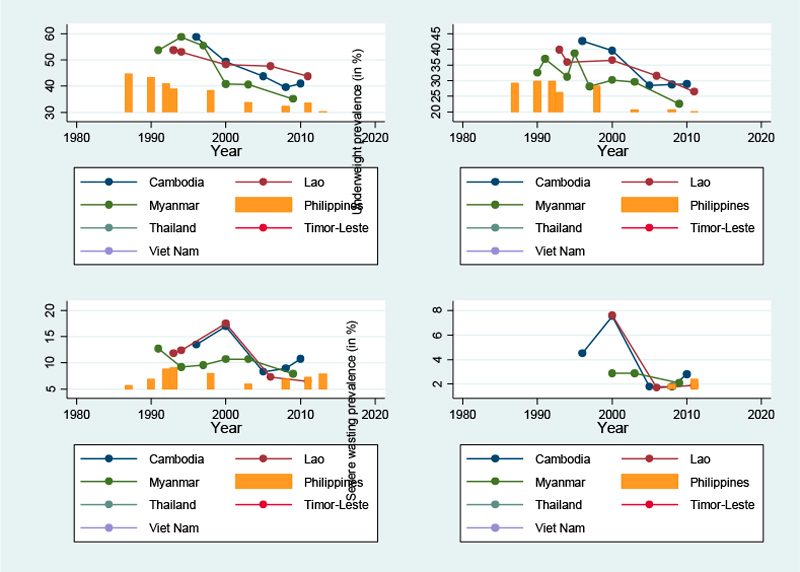

Figure 1 shows trends in child malnutrition among selected ASEAN economies.

In the Philippines, about 6 to 8% of children under five were wasted, and about 2% were severely wasted. These figures are comparable to those of Thailand. About a third of children under five in the Philippines have stunted growth, and a fifth are underweight. Just like across the world, in the Philippines, the share of children under five who had stunted growth and those underweight, have been decreasing.

When children under five are experiencing malnutrition, they are likely to carry this over to early childhood, which has repercussions on learning achievements in school.

Feeding programs

In consequence, government has developed feeding programs to reduce hunger, to aid in the development of children, to improve nutritional status and to promoting good health, as well as to reduce inequities by encouraging families to send their children to school given the incentive of being provided school feeding.

One of the chief implementers of feeding programs in the country is the Department of Education (DepED). Its school feeding programs have existed since 1997 (then called the Breakfast Feeding Program). The focus of the current DepED School-based Feeding Program (SBFP) is on dealing with undernutrition or malnutrition that is not uncommon among Filipino school-age children. In 2012, for instance, the Nutrition Status Report of DepED identified more than half a million severely wasted children enrolled in the country’s public elementary schools.

The DepED SBFP, lasting for 100 to 120 days for beneficiary schools, aims to restore at least 70% of beneficiaries (from severely wasted) to normal nutritional status, and to improve class attendance by 85-100%. The DepED also works with LGUs, NGOs and partners in the private sector, for other feeding programs outside of the SBFP. Proceeds of incomes from operations of school canteens are also allowed for school feeding.

Last year, the Department of Budget and Management provided funds to the Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS) to conduct impact evaluation studies. Such studies aim to examine whether policies, programs and projects really work, and if they do not, what needs to be changed and how. Impact evaluation essentially looks at outcomes with and without an intervention.

With my interest in examining poverty and related issues, I, together with Ana Maria L. Tabunda and Imelda Angeles-Agdeppa, am examining DepED’s SBFP. Last August 2014, we conducted a process evaluation of the SBFP aimed at examining how effectively the 2013-2014 SBPF was implemented in eight selected schools throughout the country. The evaluation seeks to identify gaps between planned and realized outcomes, and to suggest finetuning or redirecting of the SBFP, if necessary. A second phase of the study to assess actual outcomes starts next month.

The results of the process evaluation of the SBFP have been released at PIDS in a policy note. The PIDS team found the school feeding at DepED generally well managed by beneficiary schools, since school heads and other school personnel were oriented on the SBFP before it started.

We also found a number of good practices in the conduct of the school feeding. Some schools were monitoring heights and weights of children monthly. A few schools also issued “meal cards” to monitor the feeding and to ensure that only beneficiaries would be fed (see Figure 1), and some schools instituted a system of prioritization to ensure that unconsumed meals (due to absences among beneficiaries) were given to wasted children.

The SBFP appeared to work best when complemented with other DepED programs of deworming, Gulayan sa Paaralan Program (GPP), and Essential Health Care Program (EHCP).

The PIDS team noted that the SBFP is appreciated by beneficiary and volunteer parents as well as by implementers, with everyone hoping that the SBFP will be continued and expanded, if possible, to cover not only severely wasted pupils but also wasted pupils, if not all school children.

Starting school year 2014-2015, government provided substantially more resources to DepED to feed all severely wasted as against 2011-2012 and 2012-2013 budgets that allowed DepED to only feed less than a tenth (7.5%) of severely wasted children.

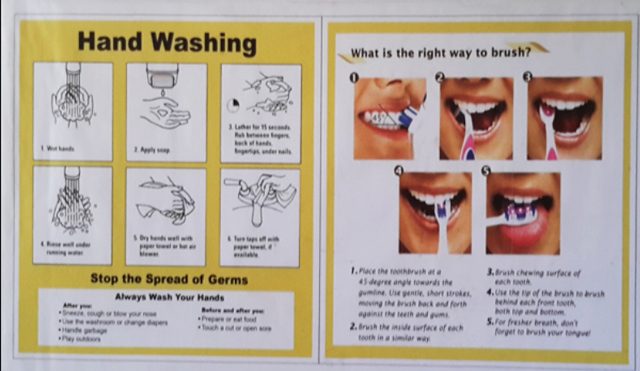

Teachers and school heads involved in the SBFP showed dedication to the program despite the extra workload. Beneficiary and volunteer parents, as well as teachers of beneficiary pupils, suggested that the SBFP provided benefits to the children in terms of improved nutritional status, better hygiene, lower morbidity during the program, improved school attendance during and even after the feeding program, increased attentiveness in class, and better social behavior.

Moreover, they regard the program as addressing child malnutrition, promoting a culture of care among stakeholders and fostering camaraderie among parents.

Room for improvement

The PIDS policy note pointed out that some aspects of SBFP implementation require improvement.

The lack of standard weighing protocols and/or weighing equipment was noted. Further, past school year data on number of severely wasted children rather than current data were used by DepED for budget allocation, which could lead to misallocation of required resources for feeding. A few schools provided sufficiently detailed documents to the PIDS research team, that allowed us to observe that these schools restored much more than 70% of beneficiaries from severely wasted to normal nutritional status.

What remains to be seen is whether this status was maintained beyond the program, but even if this is not achieved, this may not necessarily be to the fault of DepED as ultimately, proper nutrition is the responsibility of the parents.

The PIDS team noticed that procurement and liquidation were difficult for SBFP implementers to follow, and that SBFP forms were complicated. Delays in submission and acceptance of liquidation reports caused disruptions in feeding in some schools, and even in the discontinuation of the program in one case.

Heads of schools that are repeat SBFP beneficiaries attributed their smooth implementation of the program the second time around to familiarity with the routines and forms of the program and their prior experience on procurement.

Review budget

What the PIDS team suggests is that DepED reexamine the daily feeding budget for SBFP, currently at PHP 16 per beneficiary.

The DepED staff who monitor program implementation emphasized the need to increase the budget component both for the children’s food (PHP 15) and for administration and monitoring expenses (PHP 1). Inflationary adjustments have to be also considered.

While the DepED feeding program for SY 2013-2014 was managed well, we recommend that DepED provide implementing schools, perhaps through assistance of LGUs and other education stakeholders, with standard weighing equipment and measurement protocols.

In addition, SBFP school implementers need to be trained (and trained well) in the proper filling out of SBFP forms. The DepED also needs to set up and maintain a real-time information system on nutritional status of children. The Department of Budget and Management will also need to ensure timely release of budgets. Budget allocation per child ought to be increased. Parental knowledge on nutrition will need to be improved, through conduct of seminars.

There ought to be a government policy to provide sustained resources for feeding not only severely wasted children but also wasted children. Government though ought to exercise prudence in considerably increasing resources for all government programs, without learning lessons on process and impact evaluations. The current fiscal space may not always be around.

This year, 2015, the world is expected to have met the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), but clearly, there will be an unfinished agenda, and thus, this coming October, the UN will define a post 2015 Development Agenda on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

We need to renew our commitments to help those in need of most assistance, particularly children. We need to ensure that children can have a better, brighter tomorrow, and we need to start feeding them properly both in school and at home. – Rappler.com

Dr. Jose Ramon “Toots” Albert is a professional statistician who has written on poverty measurement, education statistics, agricultural statistics, climate change, macro prudential monitoring, survey design, data mining, and statistical analysis of missing data. He is a Senior Research Fellow of the government’s think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies, and the president of the country’s professional society of data producers, users and analysts, the Philippine Statistical Association, Inc. for 2014-2015.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.