SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Are we winning the fight against corruption? And if so, how can we sustain this beyond 2016? These are the questions foremost in people’s minds as the Philippines steadily improved in its credit ratings and international competitiveness rankings over the past several years, primarily on the back of good governance, as noted by analysts. More recently, the country further climbed in its overall ranking in addressing corruption based on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI).

Are we winning the fight against corruption? And if so, how can we sustain this beyond 2016? These are the questions foremost in people’s minds as the Philippines steadily improved in its credit ratings and international competitiveness rankings over the past several years, primarily on the back of good governance, as noted by analysts. More recently, the country further climbed in its overall ranking in addressing corruption based on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI).

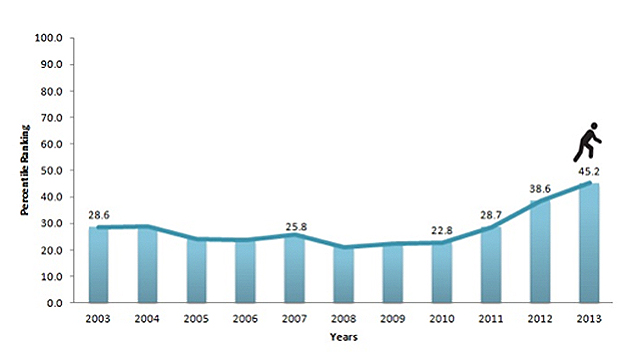

Because corruption is difficult to measure, policymakers and researchers have resorted to the next best metric – corruption perceptions. Launched in 1995 by Transparency International, the CPI helps measure countries’ progress in fighting corruption based on a survey of corruption perceptions across countries. In the past two years alone, the Philippines climbed a total of 35 notches (read: overtook 35 countries) on its CPI, so that it now ranks 94th out of 177 countries (from 105th in 2012, and 129th in 2011). If we plot the percentile rank of the Philippines (i.e. its rank as a share of total countries in the ranking) since 2003, it has clearly made impressive gains in the last three years.

FIGURE 1. Philippine Rankings in the Corruption Perceptions Index

(as a percentile of total countries ranked), 2003-2013

Source: Author’s analysis using the Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, 2003-2013

As the Philippines climbed, countries like Thailand and Indonesia slipped, perhaps due in part to the political woes recently afflicting these countries. This is a lesson for the Philippines—an impressive ascent in the rankings can also eventually turn into a depressing decline. Corruption perceptions could therefore be likened to a financial bubble—one that could burst should more substantial reforms fail to underpin people’s expectations.

TABLE 1. Corruption Perceptions Index, ASEAN Countries, 2011-2013

Country |

Published rankings |

Adjusted rankings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2013 | Change | 2011 | 2013 | Change | |

| Brunei | 44 | 38 | +6 | 44 | 38 | +6 |

| Cambodia | 164 | 160 | +4 | 157 | 160 | -3 |

| Indonesia | 100 | 114 | -14 | 95 | 114 | -19 |

| Laos | 154 | 140 | +14 | 147 | 140 | +7 |

| Malaysia | 60 | 53 | +7 | 59 | 53 | +6 |

| Myanmar | 180 | 157 | +23 | 173 | 157 | +16 |

| Philippines | 129 | 94 | +35 | 123 | 94 | +29 |

| Singapore | 5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| Thailand | 80 | 102 | -22 | 77 | 102 | -25 |

| Vietnam | 112 | 116 | -4 | 107 | 116 | -9 |

Source: Author’s analysis using Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, 2011-2013. Note: Due to the dissimilar number of countries ranked for 2011 and 2013, adjusted rankings only account for countries that were ranked by Transparency International for both years.

Changing the Corruption-Prone Environment

Anti-corruption efforts are often equated with finding “incorruptible leaders”. And when these leaders take over, a “halo effect” is expected to take place, often influencing general corruption perceptions (in turn reflected in the CPI). Leaders and public servants with integrity and competence obviously contribute heavily to the change management necessary for both the public and private sectors to reduce corruption. However, structural changes are also (and perhaps more) necessary to transform the entire economic and policy-making environment, and to make many of these gains permanent.

Extensive studies on corruption in various aspects of the economy suggest that corruption thrives in highly opaque environments, often where public sector officials are left with a high degree of discretion to interpret and apply regulations. This is also often compounded by a lack of clarity and coherence across many rules and regulations.

As regards the latter, anti-corruption advocates across the world now warn of the deliberate “misdesign” (for lack of a better word) of policies and laws so that they leave open these opportunities for rent-seeking (i.e. instead of creating new wealth, manipulating the policy environment to acquire resources).

Regulations, investment and business permit approvals may be left onerous and unclear, with too many requirements that cause bureaucratic backlogs—the very things that cause delays, which then prompt entrepreneurs and citizens to pay extra to get “expedited” services. Here, the corrupt will prefer to keep the line long and the requirements tedious, so that a regular harvest of bribes is possible. No wonder that poor provision of public goods is often the bedfellow of corruption.

Therefore, we cannot just go after the corrupt, nor should we continue to seek incorruptible “saviors”. We need to make sure the environment itself changes, so we can minimize the very opportunities for corruption itself. Better public goods and public services will do the job on that front.

Citizens as “third party monitors”

If we take stock of the reforms pursued by countries that successfully achieved impressive improvements in their corruption rankings (and subsequently preserved them), the key ingredients become apparent, namely:

- Procurement reforms that leverage electronic systems (thus minimizing the room for individual discretion, while also improving the speed and quality of services);

- Institutional reforms as part of an effort to facilitate economic integration with industrialized countries, while opening the door for citizen participation in policymaking;

- Stronger independence of audit and anti-corruption agencies, including the Office of the Ombudsman and specialized anti-corruption agencies (such as Hong Kong’s ICAC, Indonesia’s KPK and Thailand’s NACC);

- Civil service reforms that help ensure that appointments in the bureaucracy are merit-based and shielded from political influence;

- Introduction of Freedom of Information (FOI) and Right to Information (RTI) laws and policies.

Various branches of the Philippine government (from central to local) have taken important steps in key reform areas here, notably in civil service reforms, opening up the budgeting process, improving the ease of doing business in a growing number of jurisdictions, and engaging citizens and civil society groups in some aspects of the policy process. Based on this list, only the FOI law has yet to become part of the present administration’s anti-corruption strategy, yet it could be the most vital ingredient. For instance, of those countries that have rapidly and significantly turned around their governance environments from highly corrupt to better governed, Freedom of Information (or Right to Information) laws were a key part of their strategy prior to or during their ascent in their corruption rankings (see Table 2).

TABLE 2. Countries with Strongest Improvements in Ranking, Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, 2003-2013

Country | Years ranking improved significantly, 2003-2013 | Increase in ranking | Year FOI introduced |

|---|---|---|---|

| Georgia | 2005-2008, 2011, 2012 | 69 | 1999 |

| FYR Macedonia | 2004, 2007-2009 | 39 | 2006 |

| Turkey | 2004 – 2006, 2008, 2012 | 24 | 2004 |

| Poland | 2006, 2007, 2009, 2010 | 26 | 2006 |

| Ecuador | 2004, 2009 – 2011, 2013 | 11 | 2004 |

| Indonesia | 2005, 2006, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2013 | 8 | 2008 |

Source: Author’s analysis using Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, 2003-2013.Note: A significant increase in rank is defined as an increase of more than two notches in the adjusted rankings.

Numerous studies also point to the power of information-armed citizens:

- With access to information on the education budget, citizens in Uganda were able to reduce leakages in education spending that used to reach up to 87 cents for every 1 dollar allocated. After an information campaign that gave parents, teachers and communities access to budget allocation information, the leakage was driven down to about 20 cents.

- Partnering with youth groups such as the Boy Scouts of the Philippines as well as the Department of Education, the Ateneo School of Government’s G-Watch led an effort to monitor textbook purchases which helped to reduce the price of textbooks by over 40 percent, and improved the delivery rate from 60 to 95 percent.

- In India, close to 2 million right to information (RTI) requests were filed in different parts of the country within the RTI Act’s first three years of implementation. A 2009 interview of 17,000 RTI applicants found a reported success rate of 60 percent for RTI claims, such as those used to increase access to public services, investigate use of government resources and expose corruption.

There is strong international evidence supporting the case for a well-crafted and adequately implemented freedom of information law. Cases of successful implementation involved citizens, academia and civil society groups as vital partners in stamping out corruption when they actively played a “third party monitoring” role. And where the effectiveness of citizens was amply demonstrated, there was a reduced need to continue to access information using FOI laws, as the mere threat of access itself curbed corrupt acts.

Given the safeguards that could be built into the Freedom of Information law based also on international best practices, and the already extensive discussions and work done on the FOI (i.e. the first FOI bill was filed over twenty years ago), there is no reason left for delay – otherwise, all this progress in good governance (including the much ballyhooed credit upgrades and improved corruption perceptions) could dissipate very easily, just like any other bubble.

The author is Associate Professor of Economics and Executive Director of the AIM Policy Center. He thanks Aladdin Ko and Monica Melchor for their research assistance. The views expressed herein are his and are not necessarily those of the Asian Institute of Management.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.